As the financial crisis has receded, the Federal Reserve has scaled back its extraordinary provision of liquidity. Eventually, the Fed will remove all remaining monetary stimulus by raising the federal funds rate and shrinking its balance sheet. The timing of such renormalizations depends crucially on evolving economic conditions.

To many observers, the Federal Reserve’s extraordinary policy actions during the recent crisis averted a financial Armageddon and curtailed the depth and duration of the recession (Rudebusch 2009). To combat panic and dislocation in financial markets, the Fed provided an enormous amount of liquidity. To mitigate declines in spending and employment, it reduced the federal funds interest rate—its usual policy instrument—essentially to its lower bound of zero. To provide additional monetary stimulus, the Fed turned to an unconventional policy tool—purchases of longer-term securities—which led to an enormous expansion of its balance sheet.

As financial market strains eased and economic recovery began, discussion turned to how the Fed would unwind its actions (Bernanke 2010). Of course, after every recession, the Fed has to decide how quickly to return monetary conditions to normal to forestall inflationary pressures. This time, however, policy renormalization is especially challenging because of the unprecedented economic conditions and Fed actions. This Economic Letter describes various considerations in formulating an appropriate policy exit strategy. Such a strategy must unwind each of the Fed’s three key actions: the establishment of special liquidity facilities, the lowering of short-term interest rates, and the increase in the Fed’s securities holdings.

Ending the Fed’s extraordinary provision of liquidity

Starting in August 2007, money markets experienced periods of dysfunction with sharply higher short-term interest rates for commercial paper and interbank borrowing. This intense liquidity squeeze, in which even solvent borrowers found it difficult to secure essential short-term funding, appeared likely to have severe financial and economic repercussions. Therefore, the Fed, acting in its traditional role as liquidity provider of last resort, introduced a variety of special facilities to supply funds to banks and the broader financial system.

By the end of 2008, the Fed was providing over $1½ trillion of liquidity through short-term collateralized credit. Generally, this liquidity was designed to cost more than private credit when financial markets were functioning normally. Therefore, as financial conditions improved during 2009, borrowers switched to private financing. By early 2010, demand had dried up for the Fed’s special facilities and they were closed. The facilities incurred no credit losses and provided a sizable return of interest income to taxpayers. More importantly, the liquidity facilities helped limit a pernicious financial and economic crisis (Christensen, Lopez, and Rudebusch 2009).

Raising short-term interest rates

Figure 1

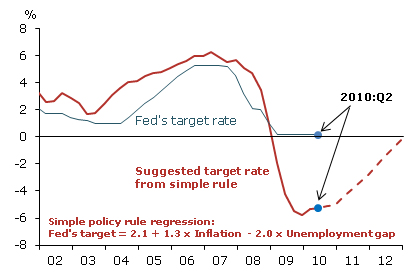

Federal funds target rate and simple policy rule

A rule of thumb that summarizes the Fed’s policy response over the past two decades can be obtained by a statistical regression of the funds rate on core consumer price inflation and on the gap between the unemployment rate and the Congressional Budget Office’s estimate of the natural, or normal, rate of unemployment (Rudebusch 2009). The resulting simple policy guideline recommends lowering the funds rate by 1.3 percentage points if inflation falls by 1 percentage point and by almost 2 percentage points if the unemployment rate rises by 1 percentage point. As shown in Figure 1, this rule of thumb captures the broad contour of the actual target funds rate during late 2007 and 2008 when, as the economy slowed, the Fed lowered its target by over 5 percentage points to essentially zero. In 2009, as the recession deepened and inflation slowed, this rule of thumb indicates that—if it had been possible—another 5 percentage point reduction in the funds rate would have been consistent with the Fed’s historical policy response. Of course, interest rates can’t really fall below zero, since any potential lender would rather hold cash. So the Fed ran out of room to push the funds rate lower and has held it near zero for over a year.

Figure 1 also provides a simple perspective on when the Fed should raise the funds rate. The dashed line combines the benchmark rule of thumb with the Federal Open Market Committee’s median economic forecasts (FOMC 2010), which predict slowly falling unemployment and continued low inflation. The dashed line shows that to deliver future monetary stimulus consistent with the past—and ignoring the zero lower bound—the funds rate would be negative until late 2012. In practice, this suggests little need to raise the funds rate target above its zero lower bound anytime soon. This implication is consistent with the Fed’s forward-looking policy guidance (FOMC 2010) that “economic conditions—including low rates of resource utilization, subdued inflation trends, and stable inflation expectations—are likely to warrant exceptionally low levels of the federal funds rate for an extended period.” This guidance indicates that the length of the “extended period” depends on the expected path of unemployment and inflation. Similarly, the benchmark policy rule would prescribe an earlier or later increase in the funds rate if unemployment or inflation rose or fell more rapidly than predicted in the forecasts underlying Figure 1.

Still, a variety of complications are ignored in the simple analysis in Figure 1. For example, the asymmetric risk associated with the zero bound on interest rates could potentially lengthen the “extended period” (see FOMC 2010). If monetary policy is tightened prematurely, it would be hard to reverse course significantly because of the zero bound constraint. However, if tightening is started late and economic growth exceeds expectations, there would be ample scope for greater monetary restraint by raising rates at a rapid pace. The greater risk associated with raising rates too early suggests postponing an initial increase in the funds rate relative to Figure 1.

In contrast, some have argued that holding short-term interest rates near zero for much longer could foster dangerous financial imbalances, such as asset price misalignments, bubbles, or excessive leverage and speculation (see FOMC 2010). The risk of such financial side effects could shorten the appropriate length of a near-zero funds rate. However, the linkage between the level of short-term interest rates and the extent of financial imbalances is quite erratic and poorly understood. For example, during the past decade and a half, Japanese short-term interest rates have been essentially at zero with no sign of building financial imbalances. Therefore, some remain skeptical that monetary policy should directly aim to restrain excessive financial speculation, especially while prudential financial regulation remains available for this task (Kohn 2010).

Figure 2

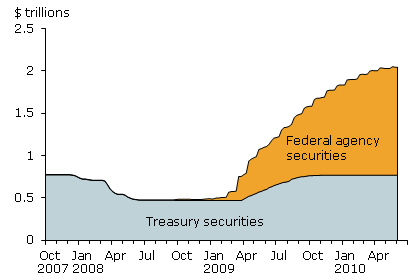

Federal Reserve securities holdings

A third factor not captured in Figure 1 is the Fed’s unconventional monetary policy. Even though the funds rate was pushed to its zero lower bound by the end of 2008, considerable scope remained to lower long-term interest rates. To do this, the Fed started buying longer-term Treasury and federal agency debt securities (including mortgage-backed securities), as shown in Figure 2. The Fed’s purchases appeared to increase the demand and price for these securities, which lowered the associated longer-term interest rates. One estimate suggests that the Fed’s announcements in late 2008 and early 2009 of future securities purchases caused 10-year yields to fall by about ½ to ¾ of a percentage point (Gagnon et al. 2010).

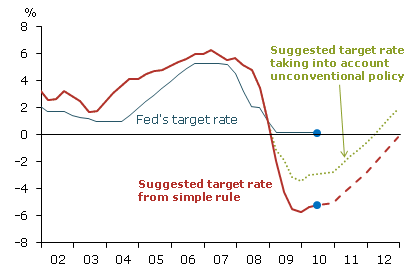

The additional stimulus from the Fed’s unconventional monetary policy implies that the appropriate level of short-term interest rates would be higher than shown in Figure 1. That is, conventional policy (the funds rate) can do less because of the stimulus to growth from unconventional policy. In calibrating this effect, it is important to note that changes in long-term interest rates have much larger effects on the economy than equal-sized changes in short-term interest rates. For example, the output sensitivity to movements in the 10-year yield estimated by Fuhrer and Moore (1995) is quadruple the output sensitivity to a short-term interest rate in Rudebusch (2002). If the Fed’s purchases reduced long rates by ½ to ¾ of a percentage point, the resulting stimulus would be very roughly equal to a 1½ to 3 percentage point cut in the funds rate. Assuming unconventional policy stimulus is maintained, then the recommended target funds rate from the simple policy rule could be adjusted up by approximately 2¼ percentage points, as shown in Figure 3, and the recommended period of a near-zero funds rate would end at the beginning of 2012.

Figure 3

Funds rate rule adjusted for unconventional policy

Returning the Fed’s balance sheet to normal

An important part of the Fed’s exit strategy involves returning the level and composition of its balance sheet to pre-crisis norms. Since conventional and unconventional Fed policies provide complementary monetary stimulus, the renormalizations of the funds rate and the Fed’s portfolio of securities should be coordinated. In theory, the Fed could respond to a faster or slower economic recovery by adjusting both the pace of tightening of the funds rate and the speed of the reductions in its securities holdings. However, there is little historical experience to help predict the timing and magnitude of the effects of selling securities. This uncertainty suggests that balance sheet renormalization should proceed cautiously and that short-term interest rates should remain the key tool of monetary policy. Indeed, a majority of the FOMC (2010) “preferred beginning asset sales some time after the first increase in the FOMC’s target for short-term interest rates.”

Figure 4

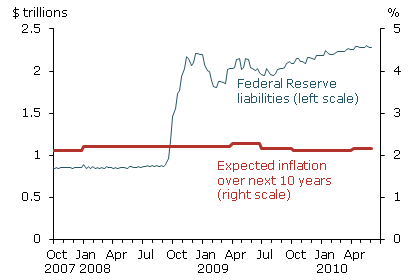

Fed’s balance sheet and expected inflation

In contrast, some worry that maintaining a large Fed balance sheet with substantial holdings of securities as assets and bank reserves as liabilities could trigger an unwelcome rise in inflation expectations and inflation. However, as shown in Figure 4, the doubling of the Fed’s balance sheet has had no discernible effect on long-run inflation expectations measured in the Survey of Professional Forecasters. This insensitivity of inflation to an enlarged central bank balance sheet is consistent with Japan’s decade-long spell of price deflation. A second worry about a continuing high level of bank reserves is that they may impede the use of short-term interest rates as the monetary policy instrument. However, the experience of foreign central banks suggests that the Fed will be able to control the level of short-term interest rates by varying the interest rate on bank reserves (Bowman, Gagnon, and Leahy 2010).

Another worry about deferring balance sheet renormalization is the potential for future losses on the Fed’s portfolio of securities if long-term interest rates rise. However, a central bank has access to an indefinite stream of future earnings from assets bought with currency (that is, seigniorage). So, many feel that, unlike for a private financial institution, such interest rate risk is of little consequence. Finally, some worry that holding Treasury securities could be seen as “monetizing” government debt, while others are concerned that holding federal agency securities gives the appearance of “allocating credit” in the private sector. Currently though, with Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac in government conservatorship, the delineation between Treasury and agency securities has been greatly blurred.

Conclusion

Many predict that the economy will take years to return to full employment and that inflation will remain very low. If so, it seems likely that the Fed’s exit from the current accommodative stance of monetary policy will take a significant period of time.

References

Bernanke, Ben. 2010. “Federal Reserve’s Exit Strategy.” Testimony before the Committee on Financial Services, U.S. House of Representatives, Washington DC, February 10.

Boman, David, Etienne Gagnon, and Mike Leahy. 2010. “Interest on Excess Reserves as a Monetary Policy Instrument: The Experience of Foreign Central Banks.” Federal Reserve Board, International Financial Discussion Paper 996.

Christensen, Jens H. E., Jose A. Lopez, and Glenn D. Rudebusch. 2009. “Do Central Bank Liquidity Facilities Affect Interbank Lending Rates?” FRBSF Working Paper 2009-13 (June).

Federal Open Market Committee. 2010. “Minutes of the Federal Open Market Committee.” April 27–28.

Fuhrer, Jeffrey C., George R. Moore. 1995. “Monetary Policy Trade-offs and the Correlation between Nominal Interest Rates and Real Output.” The American Economic Review 85, pp. 219–239.

Gagnon, Joseph, Matthew Raskin, Julie Remache, and Brian Sack. 2010. “Large-Scale Asset Purchases by the Federal Reserve: Did They Work?” FRB New York Staff Report 441 (March).

Kohn, Donald L. 2010. “The Federal Reserve’s Policy Actions during the Financial Crisis and Lessons for the Future.” Speech at Carleton University, Ottawa, Canada, May 13.

Rudebusch, Glenn D. 2002. “Assessing Nominal Income Rules for Monetary Policy with Model and Data Uncertainty.” The Economic Journal 112, pp. 402–432.

Rudebusch, Glenn D. 2009. “The Fed’s Monetary Policy Response to the Current Crisis.” FRBSF Economic Letter 2009-17 (May 22).

Opinions expressed in FRBSF Economic Letter do not necessarily reflect the views of the management of the Federal Reserve Bank of San Francisco or of the Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System. This publication is edited by Anita Todd and Karen Barnes. Permission to reprint portions of articles or whole articles must be obtained in writing. Please send editorial comments and requests for reprint permission to research.library@sf.frb.org