Interest rate derivatives—financial investments whose value depends on interest rates—provide useful information about the risk of short-term rates falling again to the zero lower bound. According to new market-based estimates, the probability of a return to the lower bound by the end of 2021 is about 24%. This is roughly in line with other survey-based and model-based estimates of zero lower bound risk. In recent months, the market-based measure of lower bound risk has increased markedly.

Over the past several months, a number of economic data releases have pointed to increased risks to the health of the economic outlook. These include weaker growth in business investment, manufacturing output, trade flows, and economic activity in foreign economies. Recent financial market data, such as lower long-term bond yields, are consistent with investors becoming more concerned about these developments. The July and September Federal Open Market Committee statements each explicitly noted uncertainties about the economic outlook in the decision to lower the target range for the federal funds rate by ¼ percentage point (Board of Governors 2019a,b).

Accurately assessing and quantifying downside risks are of paramount importance to investors, policymakers, and professional forecasters. This Economic Letter introduces and evaluates a new risk measure based on option prices in financial markets. Specifically, we use prices of Eurodollar options to estimate the probability that future short-term interest rates will return to levels near the zero lower bound (ZLB). The market’s view of this probability provides a useful model-free measure to assess both the current level of ZLB risk across different future horizons and the changes in risk perceptions over the past year.

Calculating ZLB risk from option prices

The London interbank offered rate, or LIBOR, is the benchmark interest rate for short-term loans between banks. We will focus on the U.S. dollar LIBOR, which is based on rates on interbank loans in U.S. dollars, also known as Eurodollar loans. LIBOR generally moves in tandem with other short-term interest rates, including the Fed’s policy rate, the federal funds rate. Futures and option contracts with payoffs tied to LIBOR—Eurodollar derivatives—are commonly used to calculate market-based expectations and probability distributions for future short-term interest rates. From the prices of Eurodollar options we can derive market-based probability distributions for the future value of LIBOR; for our purpose, we focus on the probability that this value is below a certain threshold associated with the ZLB. Our methodology is similar to the standard methods described, for example, in Malz (2014).

One consideration for interpreting our results is that our market-based ZLB probabilities might include risk premiums that compensate investors for the risks arising from adverse scenarios, such as a recession and return to the ZLB. But estimating risk premiums requires statistical or economic models, and a notable advantage of our market-based risk estimates is that they are model-free and available daily directly from market prices.

Ideally we would calculate these probabilities using derivatives tied directly to the Fed’s policy rate, the federal funds rate. However, options on the funds rate are much less actively traded than Eurodollar options and are only available for horizons out to one year. Thus, we rely on Eurodollar derivatives and have to contend with the fact that LIBOR does not perfectly track the funds rate. Instead, the difference between these two, typically measured with the so-called LIBOR-OIS (overnight index swap) spread, varies over time; in particular, it rises when there are concerns about the health of the banking system, such as during the 2007–2008 global financial crisis.

Since the spread tends to increase when downside risks materialize, a key question is what the level of LIBOR would be if the funds rate returned to the ZLB. As a baseline, we choose a threshold of 75 basis points, or 0.75%; this corresponds to a federal funds rate of about 10–15 basis points—its range during the ZLB period—plus a spread of 60–65 basis points. If market participants anticipated a lower (higher) value of LIBOR at the return of the policy rate to the ZLB, the true ZLB probability would be lower (higher) than our estimates.

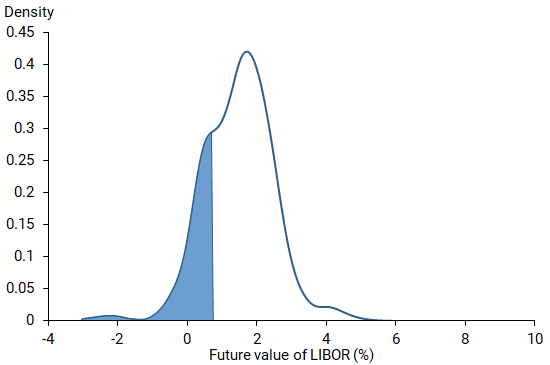

Figure 1 plots the full market-based probability density for LIBOR in December 2021, based on market prices on September 17, 2019. The probability that LIBOR will be 75 basis points at most, which corresponds to the blue shaded area under the density to the left of this threshold, is 24%. That is, investors on that day priced Eurodollar options consistent with a 24% probability of LIBOR being below 75 basis points at the end of 2021. Keeping our caveats in mind, this probability can be interpreted as the risk of returning to the ZLB by 2021.

Figure 1

Market-based probability of near-zero rates, December 2021

Note: Probability density for LIBOR in December 2021 is based on market prices as of September 17, 2019. Shaded area is probability of LIBOR falling below 75 basis points.

Current estimates of ZLB risk

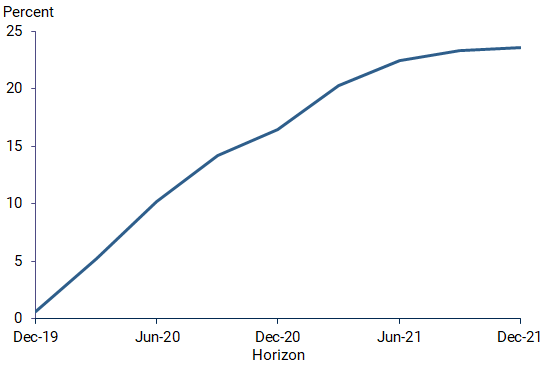

Figure 2 shows our current estimates of ZLB risk. Since Eurodollar options are available for a range of different expiration dates, we can calculate our risk measure for various future horizons. The resulting probabilities across horizons are what we call the term structure of ZLB risk, which Figure 2 plots for quarterly horizons from December 2019 to December 2021. The downside risk is small for the December 2019 horizon; this is not surprising, since LIBOR is currently around 2% and a drop to below 0.75% over the next few months is highly unlikely. The risk then increases significantly, reaching 16% by the end of 2020 and rising further to 24% by the end of 2021.

Figure 2

Term structure of ZLB risk estimates

Note: Estimates are based on market prices as of September 17, 2019.

Despite differences in methods, our medium-term ZLB risk estimate of 24% is generally in line with other estimates. For example, the median response in the June 2019 Survey of Primary Dealers by the New York Fed reported a 33% chance of a return to the lower bound by the end of 2021. Christensen (2019) reports a 17% probability of returning to the ZLB within three years, based on a model of the Treasury yield curve using data from March 2019. At that time, our ZLB risk was slightly below 15%. Lubik and Matthes (2019) used data from the third quarter of 2018 in a statistical macroeconomic model to infer a ZLB probability of only 4%; our estimates from that time fluctuated around a 5% probability.

A return to the ZLB would be the result of a recession, but a mild recession would not necessarily lead to a return to the ZLB. Thus, our estimated ZLB probability can be viewed as a lower bound for the probability of a recession over the same horizon. Current estimates of recession risk are indeed noticeably higher. For example, the New York Fed’s recession risk model in August 2019 implied a one-year recession probability of 38%. And the June Survey of Primary Dealers suggests a 44% probability that the U.S. economy will enter a recession by the end of 2020. Estimates of ZLB risk are consistent with and somewhat lower than estimates of recession risk.

Recent changes in downside risk

The level of ZLB risk based on option prices is difficult to pin down precisely, as it is based on our assumption about the level of LIBOR when the policy rate returns to its lower bound. However, changes of the estimates over time are relatively immune to changes in the underlying assumptions. Since our measure uses financial market prices, we can calculate a daily series to investigate its evolution over time and its response to specific events.

Figure 3 plots daily estimates of ZLB probabilities for a constant three-year future horizon, from January 2, 2018, to September 17, 2019 (blue line). We also include the term spread, the difference between 10-year and 3-month Treasury yields (green line). Negative levels of this spread—corresponding to long-term rates being lower than short-term rates and inverting the yield curve—have historically had strong predictive power for future recessions in the United States, thus this term spread is a popular measure of downside risk (Bauer and Mertens 2018).

Figure 3

Evolution of downside risk since January 2018

Note: Term spread reflects difference between 10-year and 3-month Treasury yields.

Until late 2018, both indicators of downside risk showed few concerns about the economic outlook. The estimated ZLB probability fluctuated mostly within a range of 4–6%. Despite the term spread trending down slightly, it remained comfortably positive. But during late 2018, both indicators started to signal a deteriorating outlook and an increase in downside risk: the estimated ZLB probability spiked up at the same time as the term spread dropped. The ensuing trend led to an inversion of the yield curve in March 2019, along with a substantially heightened risk of a return to the ZLB according to option markets.

While it is difficult to disentangle the exact drivers of the changes in ZLB risk, data indicating weakening economic conditions and increasing macroeconomic uncertainty appear to have played a major role. For example, the first peak in ZLB probability on January 3, 2019, coincided with a lower-than-expected Institute for Supply Management manufacturing data. The second significant spike occurred in March when the term spread turned negative for the first time since the Great Recession. And the most recent spikes this summer coincided with further deteriorating macroeconomic data, increased trade tensions, and rising global uncertainties.

Analyzing option prices can shed further light on the drivers of ZLB risk. An increased probability of returning to the lower bound can stem from either a downward shift in the expected path of future short rates or higher uncertainty around the expected path—or a combination of the two. Comparing recent distributions of expected future interest rates with the distributions before the late-2018 increase reveals that both factors appear to have contributed to higher ZLB risk. First, in line with the downward tilt in the yield curve and market-based policy path over this period, the central tendency of the distribution of future interest rates has shifted lower. Second, the left end of the distribution has become thicker, indicating increasing concerns about the risk of rates falling further.

Conclusion

Interest rate derivatives provide useful information about the economic outlook. In particular, option-based estimates of the probability that short-term interest rates will return to the ZLB provide a quantitative measure of downside risk. Current estimates suggest about a one-in-four chance of short-term rates dropping back to the ZLB within three years. While this implies the more likely outcome by a solid margin is that short-term rates will not return to the ZLB, the market’s view of this risk has increased substantially over the past year. Recent increases in our estimated ZLB probabilities have coincided with negative macroeconomic data and escalating international trade tensions. They also are in line with another prominent warning signal about the economic outlook: the yield curve has flattened and ultimately inverted. The elevated ZLB probability and the inverted Treasury yield curve suggest some growing concerns about the sustainability of the expansion, the possibility of a future recession, and a resulting easing of monetary policy that could push short-term rates back to their lower bound.

Michael D. Bauer is a research advisor in the Economic Research Department of the Federal Reserve Bank of San Francisco.

Thomas M. Mertens is a senior research advisor in the Economic Research Department of the Federal Reserve Bank of San Francisco.

References

Bauer, Michael D. and Thomas M. Mertens. 2018. “Information in the Yield Curve about Future Recessions.” FRBSF Economic Letter 2018-20 (August 27).

Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System. 2019a. “Federal Reserve Issues FOMC Statement.” Press release, July 31.

Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System. 2019b. “Federal Reserve Issues FOMC Statement.” Press release, September 18.

Christensen, Jens H.E. 2019. “The Risk of Returning to the Zero Lower Bound.” FRBSF Economic Letter 2019-14 (May 13).

Lubik, Thomas A., and Christian Matthes. 2019. “How Likely Is the Zero Lower Bound?” Economic Quarterly 105(1), FRB Richmond.

Malz, Allan M. 2014. “A Simple and Reliable Way to Compute Option-Based Risk-Neutral Distributions.” FRB New York Staff Report 677 (June).

Opinions expressed in FRBSF Economic Letter do not necessarily reflect the views of the management of the Federal Reserve Bank of San Francisco or of the Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System. This publication is edited by Anita Todd and Karen Barnes. Permission to reprint portions of articles or whole articles must be obtained in writing. Please send editorial comments and requests for reprint permission to research.library@sf.frb.org