Thank you for a very interesting question!

As many people know, the prime interest rate, or prime rate, is a commonly used reference rate for floating interest rate small business and consumer loans offered by banks. Individual loan rates often are set at some discount or premium to the prime rate, such as prime plus 1 percent. LIBOR, which stands for London Interbank Offered Rate, is the interest rate at which major international banks are willing to offer Eurodollar deposits to one another. Finally, the federal funds rate is the rate U.S. banks charge on overnight loans to banks that need to borrow to meet their reserve requirements. The target federal funds rate, set by the Federal Open Market Committee, is the most commonly used tool of U.S. monetary policy.

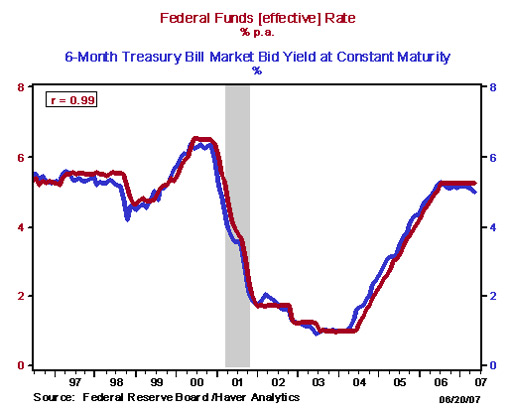

Indeed, there is a very high correlation between the funds rate and other short-term interest rates. For example, as shown in Figure 1, the correlation between the overnight federal funds rate and a six-month Treasury bill rate is 0.99 (the highest correlation coefficient possible is 1.00).

Figure 1

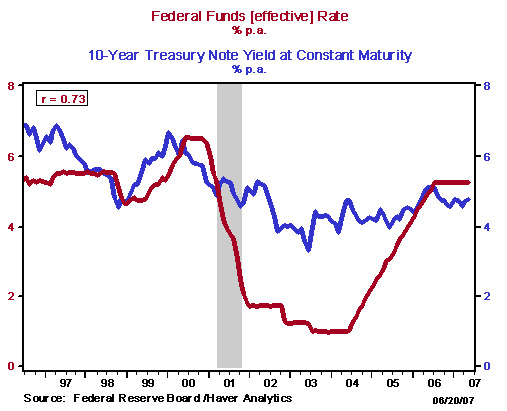

There also is a strong correlation between the effective federal funds rate and longer-term interest rates. As shown in Figure 2, the correlation between the federal funds rate and the ten-year Treasury bill rate is 0.73.

Figure 2

As for the size of the interbank loan market, it is rather large, with daily loans between banks—fed funds would account for the largest share these—averaging over $300 billion dollars a day in 2006. In this market, the bulk of the $300 billion dollars in loans are either repriced daily or traded every day.

The following excerpts from Fed resources might help you to understand the link between the federal funds rate and other interest rates in the economy:

1. Website of the Federal Reserve Bank of NY: “About the Fed” section:

The fed funds rate can be viewed as the marginal cost of borrowing for banks, which banks must consider when setting the interest rate they charge borrowers:

Movements in the federal funds rate have important implications for the loan and investment policies of all financial institutions, especially for commercial bank decisions concerning loans to businesses, individuals, and foreign institutions. Financial managers compare the federal funds rate with yields on other investments before choosing the combinations of maturities of financial assets in which they will invest or the term over which they will borrow. Interest rates paid on other short-term financial securities—commercial paper and Treasury bills, for example—often move up or down roughly in parallel with the funds rate. Yields on long-term assets—corporate bonds and Treasury notes, for example—are determined in part by expectations for the federal funds rate in the future.

2. October 11, 2002 Economic Letter, "Setting the Interest Rate":

This article explains that short-term interest rates may move together because they are close substitutes:

Why do movements in the federal funds rate influence the [repo or] RP rate and other short-term market rates? Suppose a commercial bank wants to raise overnight funds on short notice. It might borrow reserves in the federal funds market, or it might sell securities "under repo." In the former case, the bank borrows at the federal funds rate; in the latter case, it borrows at the RP rate. Because there are only minor differences in the quality of the two assets, their rates remain very closely tied together due to the elimination of arbitrage opportunities that would otherwise exist for banks who participate in both markets. Similarly, other short-term money market interest rates respond in kind in order to maintain a portfolio balance under which all assets yield the same expected return after adjusting for risk, maturity, and liquidity differences. Hence, when the Fed adjusts its target for the federal funds rate, all other short-term interest rates tend to move with it. Indeed, some short-term interest rates may change in anticipation of the change in the target.

3. A 2004 speech on monetary policy by then-Governor and now Federal Reserve Board Chairman Ben Bernanke.

The following excerpt explains how expectations link short-term interest rates:

Although the relation between the FOMC’s setting of the federal funds rate and the more economically relevant long-term yields is hardly direct or mechanical, a critical connection does exist. The connection operates less through the current value of the funds rate, however, than through the interest-rate actions that the FOMC is expected to take in the future. Specifically, financial theorists and market practitioners concur that, with risk and term premiums held constant, long-term yields move closely with the expectations that financial-market participants hold about the future evolution of the funds rate and other related short-term rates. For example, all else being equal, if short-term rates are expected to be high on average over the relevant period, then longer-term yields will tend to be high as well. Were that not the case, investors would profit by holding a sequence of short-term securities and declining to hold long-term bonds, an outcome inconsistent with the requirement that, in equilibrium, all securities must be willingly held. Likewise, if future short-term rates are expected to be low on average, then long-term bond yields will tend to be low as well.

References

Booth, James. (1994) “The Persistence of the Prime Rate.” Federal Reserve Bank of San Francisco, FRBSF Weekly Letter, Number 94-20; May 20, 1994.

Federal Funds. (2007) Fedpoints. Federal Reserve Bank of New York.

Furlong, Fred. (1991) "Is the Prime Rate Too High?" Federal Reserve Bank of San Francisco, FRBSF Weekly Letter, Number 91-25; July 5, 1991.

Instruments of the Money Market. (2006) Federal Reserve Bank of Richmond.

Laderman, Elizabeth. (1990) “The Changing Role of the Prime Rate.” Federal Reserve Bank of San Francisco, FRBSF Weekly Letter, July 13, 1990.

Marquis, Milton. (2002) “Setting the Interest Rate.” Federal Reserve Bank of San Francisco, FRBSF Economic Letter, Number 2002-30; October 11, 2002.

Mishkin, Frederic S. and Stanley G. Eakins. (2000) Financial Markets and Institutions. Addison-Wesley: Reading, Massachusetts.

Selected Interest Rates. Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System, Federal Reserve Statistical Release H.15.

Survey of Terms of Business Lending. Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System, Federal Reserve Statistical Release E.2.