The pandemic made clear that our economic lives are more interdependent than we may have realized in the past, which has important implications for how we think about our shared economic future. In a new SF Fed working paper coauthored with President Mary C. Daly, we find that labor market disparities by gender and race cost the U.S. $2.6 trillion in foregone GDP in 2019, and we estimate that these annual costs will continue to grow, reaching $3.1 trillion in 2029.

The study contributes to a growing body of research that demonstrates that a more inclusive and equitable economy creates significant economic benefit for the entire nation.* It also shows the enormous economic cost of persistent inequities over the past thirty years, which adds up to $70.8 trillion in lost output since 1990.

Systemic inequities that limit the full potential of women and people of color bear real economic costs for every American, suggesting that there are material economic gains from equity.

Historical trends: Employment and education

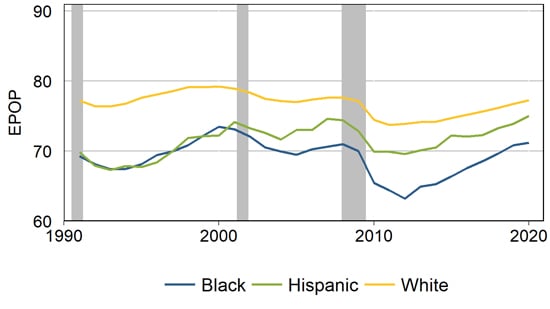

The paper begins by plotting trends in labor opportunities and outcomes for adults age 25–64 to observe differences by race and gender. For example, Figure 1 shows trends in the employment to population ratio by race and ethnicity, revealing that whites have higher employment rates than Blacks and Hispanics. There’s some evidence that the gaps narrow during economic expansions, but even those times of economic growth are insufficient to close them.

Figure 1. Trends in Employment (25–64)

Employment to population ratio

From 1990–2019, whites had consistently higher employment rates than Blacks and Hispanics. (Source: Author’s calculations using CPS data)

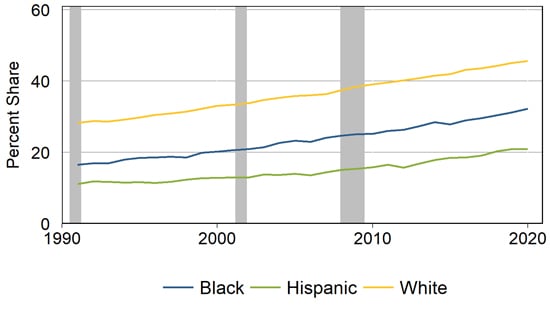

Figure 2 explores gaps in educational attainment, showing the share of individuals with a bachelor’s degree or higher. A larger share of whites has completed a BA compared to Blacks and Hispanics, reflecting underlying structural barriers and gaps in opportunity for people of color. The trends by gender are different, as the share of college educated women began rising rapidly in the early 2000s to surpass that of men.

Figure 2. Trends in Educational Attainment (25–64)

Share of population with a BA or higher

From 1990–2019, a larger share of whites had a BA compared to Blacks and Hispanics, reflecting underlying structural barriers for people of color. (Source: Author’s calculations using CPS data)

Historical trends: Utilization and occupation

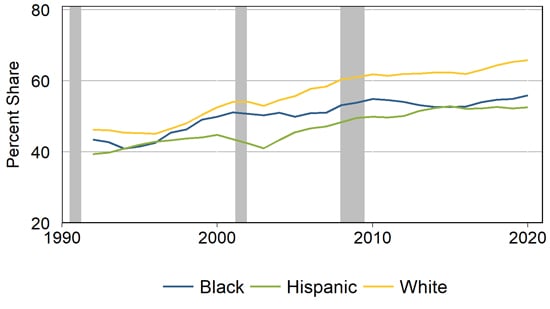

Even when people have a BA, they may end up in jobs that do not fully utilize their education, which results in an underutilization for the entire economy. Figure 3 shows educational utilization, measured as the share of BA holders who are in jobs that require that degree. Utilization rates are higher for whites, and the gaps have grown over time. The pattern is different by gender as women are consistently utilized at a higher rate than similarly educated men and that gap has narrowed over time.

Figure 3. Trends in Educational Utilization (25–64)

Share of BA+ degree holders in jobs that require that degree

From 1990-2019, a larger share of whites with a BA were in jobs that require that degree compared to similarly educated Blacks and Hispanics. (Source: Author’s calculations using CPS data)

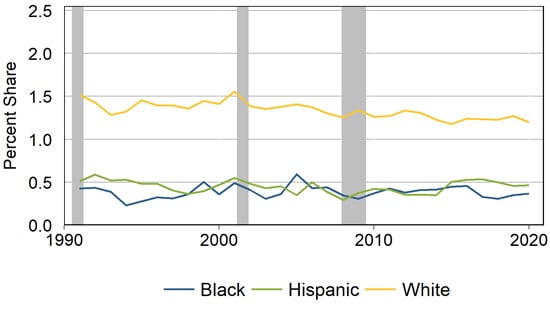

The final trend highlighted in the paper is opportunity across industries and occupations. As an example, Figure 4 shows the share of individuals who have a professional occupation in the durable goods—such as cars, appliances, or electronics—manufacturing sector, as these are among the highest paid workers in that industry. Whites are consistently much more likely to hold these jobs than Blacks and Hispanics, and this is true to an even larger degree for men in comparison to women.

Figure 4. Trends in Industry-Occupation Distribution (25–64)

Share of professionals in durable goods manufacturing

From 1990-2019, whites were more likely to have a professional occupation in the durable goods manufacturing sector compared to Blacks and Hispanics. (Source: Author’s calculations using CPS data)

Our thought experiment: Closing gaps in labor market opportunities and outcomes

With an understanding of these historical gaps, our research estimates their aggregate cost. To conduct our thought experiment, we imagine a counterfactual world in which labor market gaps do not exist and estimate the economic impact of eliminating these gaps. We replace the employment rates and hours worked, as well as the shares of educational attainment, utilization, and industry-occupation distribution, for women and people of color with those of white men, who are the default group in our analysis because they’ve historically faced fewer systemic barriers in the labor market. To examine the returns to opportunity, we measure labor productivity using average hourly earnings. Finally, we estimate the impact on aggregate output.

Employment and hours gaps

Our first experiment asks how much more output the U.S. economy would have had if historical gaps in employment and hours had been closed. In 2019, closing gaps by both race and gender would have increased the employment to population ratio by 8 percentage points and added 2.4 hours to the average work week. We then estimate the dollar value of closing these gaps. For example, equalizing employment by race and gender would have boosted GDP in 2019 by $0.63 trillion, and equalizing hours would have added $0.37 trillion.

Education, utilization, and industry-occupation gaps

We next examine closing gaps in labor productivity, which in our model is influenced by education, utilization, and industry-occupation distribution, and measured with average hourly earnings. For example, in this experiment, we would close the gap between the share of Black and white men that have a college degree, but that share of Black men would still maintain their actual average hourly earnings. Closing the gaps in the determinants of productivity changes aggregate average hourly earnings only slightly. For example, closing gaps across education, utilization, and industry-occupation distribution by race and gender in 2019 increases average hourly earnings by 62 cents. This would translate to an estimated increased GDP in 2019 of $0.17 trillion.

Earnings gaps

We also conduct an additional exercise to acknowledge that the returns to opportunity vary by race and gender in ways that are not fully explained by differences in skills, utilization, or other measurable variables. It’s likely that discrimination and bias play a key role as unobservable variables. For that exercise, we keep the determinants of labor productivity fixed at their actual values and only adjust the returns earned by race and gender. For example, we would keep the proportion of college educated Black women age 25–34 at their actual share but assign this group the average hourly earnings of their white male counterparts. The impact to GDP is significant. Eliminating the earnings gap would have increased GDP nearly six times more than the impact of our previous experiment, where we adjusted labor productivity shares but kept average hourly earnings at their actual values.

Closing all the gaps

Putting this all together, our final experiment closes all gaps in labor inputs, determinants of productivity, and the returns measured in average hourly earnings. We acknowledge this is not a general equilibrium model, but the bottom line of our analysis shows that the U.S. economy would have had about $2.6 trillion dollars more output in 2019 if gaps in labor market opportunities and returns were eliminated. Our results show that the gains have been rising over time as the U.S. population becomes more racially diverse. When we add it up over thirty years, we estimate that equalizing opportunities and returns would have resulted in aggregate gains of $70.8 trillion.

The economic gains of a more equitable future

So what does all of this mean? In this paper, we focus on closing the gaps, but it’s important to acknowledge that these gaps are rooted in systemic inequities. Explicitly racist policies like Jim Crow laws and redlining have had lasting effects on residential segregation and wealth accumulation for communities of color, especially Black communities, which create barriers to education and labor market opportunities. In addition, the existence of labor market discrimination at the individual level is also well-documented, and together these have implications for policies that address both structural racism and workplace discrimination. There are also important structural impediments to full economic participation for women, such as limited options for child care or paid leave, and we must consider the compounded labor market barriers that women of color face.

Our decomposition reveals that the gaps cannot be fully explained by observable measures of talent or skill, indicating that gender and race are still meaningful predictors of labor market outcomes. Although our analysis runs from 1990-2019 and thus does not include the effects of the pandemic, we’re seeing firsthand the implications of these inequities in the context of COVID-19, which is causing disproportionate harm to the labor market outcomes of women and people of color. In addition, it is important to consider future gains if opportunity gaps along race and gender were closed. Using population projections from the Census Bureau, we estimate that closing opportunity gaps for women and people of color would increase economic output by an additional $3.1 trillion in 2029 alone.

The findings should compel us to move with urgency to eliminate inequities, both because it’s the right thing to do and because it will be critical to maintaining global competitiveness. In short, achieving gender and racial equity is crucial to our shared economic future.

Read the paper “The Economic Gains from Equity.”

Shelby R. Buckman is a research associate in Economic Research at the Federal Reserve Bank of San Francisco.

Laura Choi is vice president of Community Development at the Federal Reserve Bank of San Francisco.

Lily M. Seitelman is a research associate in Economic Research at the Federal Reserve Bank of San Francisco.

Image credit: Angelina Bambina via iStock.

You may also be interested in:

* For example: Lisa D. Cook. “Racism Impoverishes the Whole Economy,” New York Times, November 18, 2020; Chang-Tai Hsieh, Erik Hurst, Charles I Jones, and Peter J Klenow. The Allocation of Talent and US Economic Growth. Econometrica, 87(5):1439–1474, 2019; Dana M. Peterson and Catherine L. Mann. “Closing the Racial Inequality Gaps: The Economic Cost of Black Inequality in the U.S.” Citi GPS: Global Perspectives & Solutions, 2020; Sarah Truehaft, Justin Scoggins, and Jennifer Tran. “The Equity Solution: Racial Inclusion Is Key to Growing a Strong New Economy,” PolicyLink/PERE Research Brief, 2014.

The views expressed here do not necessarily reflect the views of the management of the Federal Reserve Bank of San Francisco or of the Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System.