Watching the rise of new payment innovations feels exhilarating. I admit that I rarely use cash and like to try out new ways to pay for things as an early adopter of financial technology products. But as exciting as the future of payments is, we need to remain mindful that racing towards it can leave some people without a way to purchase everyday necessities.

It’s my job with the Federal Reserve’s Cash Product Office (CPO) to analyze and understand how people prefer to pay for things. So, recent media coverage about cities like Philadelphia and San Francisco banning cashless businesses have grabbed my attention.

No federal law requires stores to accept cash as a form of payment, although it is legal tender for all debts, public and private. And if private businesses are free to do as they wish, why pass laws saying companies must accept cash? The main argument is financial inclusion: not everybody has a bank account, and some people only use cash. Are you going to discriminate against them by not accepting their only form of payment? It’s a fair argument.

Lawmakers recognize that businesses aren’t necessarily being malicious by refusing cash. It’s an effective way to keep costs down, speed up transactions, and minimize the risk of robbery or employee theft. But these benefits are seemingly overshadowed by the impact on the population relying on cash the most: the unbanked.

Unbanked and underbanked people are most at risk when cash isn’t an option. Unbanked individuals don’t have checking or savings accounts. Underbanked people have a checking or savings account, but also use alternative financial services such as money orders, check cashing, international remittances, and payday loans.

So what exactly is happening with unbanked and underbanked individuals? To find out, I recently dove deeper into the data from the CPO’s latest Diary of Consumer Payment Choice, an annual study looking at payment usage behaviors in the United States.

I had a few questions I wanted to answer.

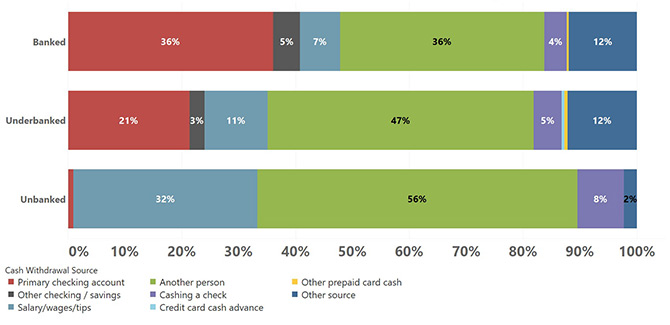

Where is everyone getting their cash?

There’s a leading assumption that unbanked individuals only use cash, but they certainly aren’t getting it from ATMs. Where are they getting it? Primarily from their employers and other people, and at a much higher frequency than other groups.

Unbanked receive cash from work and other people

Even though the banked and underbanked populations also receive cash from other people at very high rates, they otherwise pull cash from their checking accounts. The high rate the unbanked receive cash from their employers implies that they are being paid their wages in cash, while other groups may receive cash as tips from work.

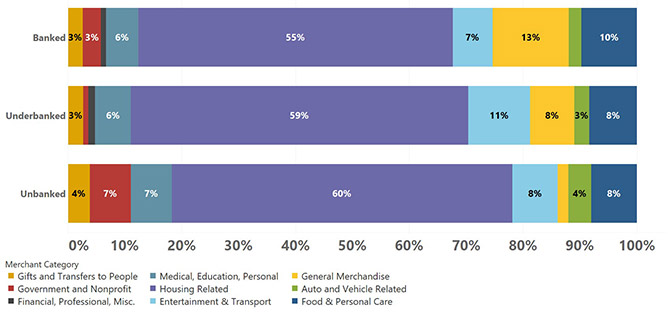

Where is their money going?

There isn’t much of a difference with how banked, underbanked, and unbanked people spend their money. Almost everyone’s income goes to housing-related expenses like rent and mortgage.

Spending habits are consistent across groups

The unbanked population spends far less on general merchandise when compared to the banked and underbanked. However, spending habits looks similar for all groups when the analysis includes all payment instruments (cash, credit, debit, check, electronic, etc.).

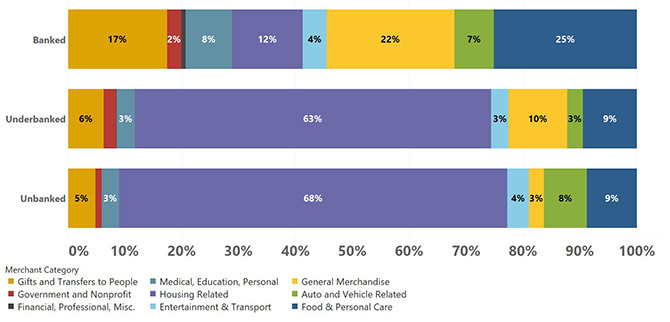

Where is their cash going?

Does anything change when we only look at cash? Absolutely.

Financial underserved groups use cash for housing expenses

Banked populations use cash to pay for general merchandise and food and personal care items, or to pay other people. People who are unbanked or underbanked use cash to pay their rent or mortgage. Not only is their most significant expenditure housing, but they pay for it with cash.

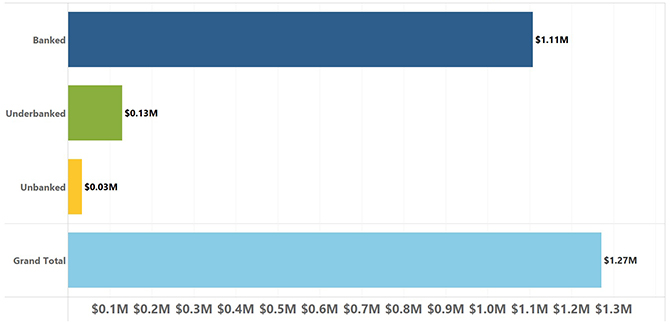

Final question: What’s the financial impact?

Spending reported in our Diary, which covers the month of October 2018, totals $1.3 million. Of that, only $30,000 is attributed to unbanked individuals. The underbanked population spent $130,000. Banked individuals spent the remainder of the $1.1 million.

Unbanked are a small fraction of total spending

When we chart out unbanked spending, we see an incredibly small bar. But that bar represents 14.1 million people.

In this case, the unbanked population spends far too little to make a ripple in our data sets. Yet their reliance on cash means that they disproportionately feel the effects of financial technology innovations that impact cash acceptance.

Bottom line

Many people may not show up in macro-level data and that’s important for policymakers to keep in mind.

When governments, whether on a local or national level, look at total spending trends, they can easily overlook large groups of our population.

As for the Fed, we want to make sure our work and research around cash and payments supports an economy that allows everyone to participate. Cash is, after all, one of the most inclusive payment instruments.

Raynil Kumar is a policy analyst in the Federal Reserve’s Cash Product Office. You’ll find him working on the Fed’s currency quality program, researching consumer payment behaviors, and informing cash policies throughout the United States. He’s a fan of blazingly spicy food, filmmaking, and turtlenecks.

You may also like:

The views expressed here do not necessarily reflect the views of the management of the Federal Reserve Bank of San Francisco or of the Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System.