As part of their efforts to promote economic recovery, some central banks have announced they will not raise policy rates for specified time periods. Other central banks have not been as explicit, though they have provided guidance. A comparison of the effects of the Bank of Canada’s conditional promise to hold rates steady through the second quarter of 2010 with the Federal Reserve’s less explicit guidance finds no evidence that market participants make distinctions between these statements.

Central banks around the world reacted to the recent financial crisis by cutting interest rates. Many also provided guidance about future policy. While central banks have been making statements about future policy for many years, an unusual element this time was that some banks explicitly stated how long they expected to keep policy rates unchanged. This Economic Letter discusses why central banks make statements about future policy and asks whether market expectations of future policy are sensitive to announcements that rates will be held unchanged for specific periods. We compare the recent experience of Canada—where a specific date was announced—with that of the United States, where no specific date was cited.

What central banks say about future policy and why

After recent meetings, the Federal Open Market Committee has been using a variant of the following from the August 12 statement to provide guidance about the future path of monetary policy: “The Committee … continues to anticipate that economic conditions are likely to warrant exceptionally low levels of the federal funds rate for an extended period.” How long this “extended period” might be has not been spelled out. By comparison, the Bank of Canada has been more explicit. On April 21, it stated: “Conditional on the outlook for inflation, the target overnight rate can be expected to remain at its current level until the end of the second quarter of 2010.” This has been repeated more or less verbatim in subsequent announcements.

Why do central banks issue statements about future monetary policy? As Woodford (2005) points out, the public’s expectations of future policy are critical to effective monetary policy. Although central banks control current overnight interest rates, these do not matter much for economic decisions. Instead, what matters is the expected path of short-term interest rates, which influences long-term interest rates today. Thus, the ability of central banks to influence the economy today depends upon their ability to shape market expectations about the path of policy rates in the future. Using public statements to guide expectations about future short-term rates can become especially important for the kind of situation that many central banks find themselves in today, in which economies are weak and short-term rates are already effectively at zero.

Announcements about the future paths of short-term rates are not without risks, though. Economic conditions may change in unexpected ways, making it necessary for central banks to deviate from preannounced paths. This might cause banks to lose credibility and cause disruptions in financial markets as well as the economy at large. For this reason, central banks are cautious when discussing future policy and are usually unwilling to make unequivocal statements about future policy (see Rudebusch and Williams 2008 and Dale, Orphanides, and Osterholm 2008).

But careful statements may not have the same impact as unequivocal ones. If market participants believe policymakers are hedging, they will be cautious about the actions they take in response. So, central banks face a tradeoff: Make an explicit statement that may have a substantial impact now with the risk of problems in the future, or avoid the risk and make a more cautious statement that may have only a marginal impact.

Recent experiences in Canada and the United States

We compare the impact on market expectations of Canada’s more explicit statement about future policy with the Federal Reserve’s less explicit statement. It’s useful to keep two things in mind: First, when talking about future policy, the Fed typically stresses the need to “promote economic recovery and to preserve price stability.” Thus, we expect market federal funds rate projections will be affected by news about both output and inflation. Second, the Bank of Canada has been careful to point out that its commitment is conditional, which means that markets should expect a rate increase before the middle of next year if inflation becomes a problem.

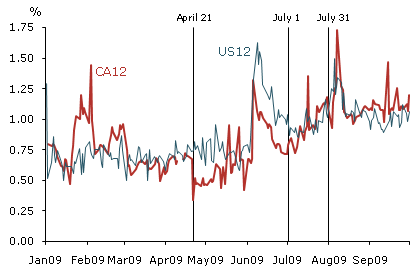

Figure 1

Expected policy rates, 12 months ahead

To examine expectations about future policy, we use measures derived from overnight index swaps, which are contracts to exchange an overnight interest rate for some fixed rate. Using daily data from January 1 to September 30, Figure 1 plots market expectations of the policy rate for the 30-day period ending 12 months in the future. Consider first the Canadian rate (CA12). Although volatile in the early part of the year, by mid-March it had settled into a narrow range between 0.50 and 0.75 percentage point. The Bank’s April 21 announcement (indicated by the first vertical line in Figure 1) that it would keep interest rates unchanged until the end of the second quarter of 2010 had an immediate effect on the CA12 rate, which fell by more than 50%. The corresponding U.S. rate (US12) showed no such response.

But the Canadian rate began moving back up the very next day. Perhaps the most noticeable move took place June 5—one day after the Bank reiterated its commitment to keeping the policy rate at the effective lower bound—when the 12-month future rate jumped up by more than 0.5 percentage point to exceed 1¼ percent. It is hard to find news about the Canadian economy that would explain this increase. In fact, on June 5 the Canadian Labor Survey reported that the May unemployment rate had increased more than expected. More relevant perhaps was the fact that U.S. rates went up sharply at the same time, which commentators attributed to the release of better-than-expected labor market data that day.

Given the relative size of the U.S. and Canadian economies and the many linkages between them, Canadian rates often respond to developments in the United States. But why should this pattern persist even after the Bank of Canada issued a conditional commitment to keep rates unchanged over this period? Such a commitment might be expected to make Canadian rates less sensitive to developments elsewhere. Thus, one could conclude that the Bank’s statement was not credible. On the other hand, the tight linkages between the two economies also imply that good U.S. economic news is likely to be good for Canada as well. So, the good U.S. news could be signaling that the Canadian economy would recover faster than expected, which in turn could mean heightened inflation risk. Under this interpretation, the rate increase would not imply that the Bank lacked credibility but that the condition mentioned in the statement might be met, setting the stage for the Bank to raise rates to keep inflation contained. This example illustrates how difficult it can be to interpret rate movements when central banks issue conditional statements.

In Figure 1, also note that the Canadian rate reversed direction almost immediately after the June 5 jump (just as the U.S. rate did) and continued to fall over the next few weeks. Even so, at the end of June, markets were expecting the Bank to raise rates by about 0.5 percentage point at some point within the “commitment window,” that is, the period for which the Bank promised to keep rates unchanged.

Zeroing in on the end of next year’s second quarter

Data that span the end of the Bank of Canada’s commitment period provide another way to measure the effect of its statement. Specifically, we can compare market participants’ expectations of interest rates at the end of the second quarter with their expectations for the beginning of the third quarter. If market participants believe that the Canadian commitment will keep rates below what they would otherwise be, then we would expect them to anticipate an increase after the commitment expires. We can also compare Canadian forward rates with those in the United States, where the end of the second quarter has no special significance.

Figure 1 shows the Canadian rate rose noticeably in July. This is significant because the 30-day period covered by CA12 begins to move out of the commitment window starting with data for July 1 (indicated by the second vertical line in the chart). By the end of July (the third vertical line in the chart), the 30-day period covered by CA12 lies entirely outside the commitment window. Thus, one could argue that the rise in the CA12 rate over July shows that market participants are convinced that the Bank of Canada will keep rates lower than they would otherwise be through the end of June 2010. But other data suggest this interpretation is problematic.

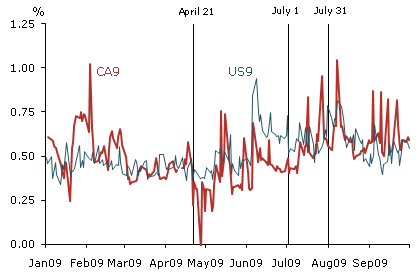

Figure 2

Expected policy rates, 9 months ahead

Consider, first, the US12 rate in Figure 1. Despite some deviations, the rise in US12 over the past few months has been similar to the rise in CA12 (including the spikes in mid-July and early August). Because June 30, 2010, has no special significance for the United States, some other common factor must be pushing both rates upwards. However, this comparison does reveal an interesting detail: CA12 was, on average, lower than US12 in the period from April 21 (the date of the Canadian announcement) to the end of June, but rose to roughly equal the U.S. rate after the data moved out of the commitment window. Does this increase in rates imply that the Bank’s commitment was keeping Canadian rates lower than otherwise?

Figure 2 provides the answer. It compares the policy rate expected to prevail in Canada over the 30-day period that ends nine months in the future (labeled CA9) with the corresponding U.S. rate (US9). This horizon is interesting because even the observations at the end of the sample are entirely within the Bank’s commitment window. Note that CA9 was below US9 prior to the beginning of July, after which it moved up, both absolutely and relative to the U.S. rate. These relative movements are exactly what we saw for the 12-month rates. But because the 9-month rates in Figure 2 never move out of the Bank of Canada’s commitment window, the higher Canadian rates since July cannot be attributed to the Bank’s commitment. It is more likely that the rise in rates reflects incoming economic data.

Conclusion

The Bank of Canada’s commitment to leave rates unchanged did affect interest rates initially, but the effect does not appear to have persisted. Market participants expect the Bank to raise rates as the economy strengthens. This doesn’t necessarily mean the Bank is not credible. It has stressed that its commitment is conditioned on the inflation outlook. At the same time, U.S. and Canadian forward rates are closely correlated on either side of the commitment’s expiration date. So we find little to suggest that the announcement of a fixed end date has significantly affected expectations of future monetary policy in Canada. It seems that market participants see little difference between the U.S. phrase “extended period” and Canada’s conditional commitment to keep rates fixed for a specified period.

References

Bank of Canada. 2009. “Press Release,” April 21.

Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System. 2009. “Press Release,” August 12.

Dale, Spencer, Athanasios Orphanides, and Par Osterholm. 2008. “Imperfect Central Bank Communication – Information versus Distraction,” International Monetary Fund Working Paper 08/60.

Rudebusch, Glenn D., and John C. Williams. 2008. “Revealing the Secrets of the Temple: The Value of Publishing Central Bank Interest Rate Projections.” In Monetary Policy and Asset Prices, ed. John Campbell. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, pp. 247-284.

Woodford, Michael. 2005. “Central Bank Communication and Policy Effectiveness.” Paper presented at the FRB Kansas City Symposium “The Greenspan Era: Lessons for the Future,” Jackson Hole, Wyoming, August 25-27, 2005.

Opinions expressed in FRBSF Economic Letter do not necessarily reflect the views of the management of the Federal Reserve Bank of San Francisco or of the Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System. This publication is edited by Anita Todd and Karen Barnes. Permission to reprint portions of articles or whole articles must be obtained in writing. Please send editorial comments and requests for reprint permission to research.library@sf.frb.org