Total business loans under $1 million held by small U.S. banks continue to dwindle. Disproportionate negative growth at financially weak small banks has been an important factor in this decline. Loan volumes at strong small banks actually grew in 2011. The finding supports the view that supply conditions, not just tepid demand for credit, have affected bank lending to small businesses.

Total business loans under $1 million held by small U.S. banks are shrinking. Although dollar volumes fell at a slower pace in the four quarters that ended in June 2012 than over the previous year, the persistent decrease remains a concern. A previous Economic Letter (Laderman and Gillan 2011) presented data suggesting that trends in aggregate nonperforming asset ratios for business loans under $1 million held by small banks may be related to trends in the growth of those loans. This Letter shows the relationship between growth in business loans of this size and the lender’s overall financial condition. Financially weak small banks, though they are in the minority, have accounted for most of this loan shrinkage. In fact, business loans under $1 million at strong small banks actually grew in 2011.

Small banks, small businesses, and the economy

By a rough estimate, about one in seven small businesses uses credit from a small bank, defined as a bank with assets under $1 billion. According to the 2003 Survey of Small Business Finances, the most recent survey in this series (Mach and Wolken 2006), about 40% of small businesses use bank credit in the form of credit lines or loans, excluding credit card loans. Data from regulatory financial statements known as Call Reports indicate that small banks hold about 41% of all bank non-credit card business loans and lines under $1 million. Most loans of this amount probably go to small businesses. Of course, some credit to small businesses takes the form of loans or lines over $1 million. Large banks are more likely to provide credit in such amounts.

These estimates may understate the importance of small bank credit for the economy. Relatively young businesses generate a large share of new jobs. Small banks may have a comparative advantage over large banks in lending to such businesses. Newly established businesses may have few assets or assets that are difficult to value as collateral. Lender underwriting and monitoring may have to rely heavily on information about the creditworthiness of the business owners—their “character,” skills, and other personal attributes. Small banks may be able to analyze and use this kind of subjective information more effectively than large banks because fewer layers of management are involved in lending decisions.

Such a comparative advantage may mean that a small business that obtains credit from a small bank may not easily find financing at a large bank if its current bank curtails lending, especially in an environment of economic uncertainty, when creditworthiness may be particularly hard to judge. Indeed, business loans under $1 million at large banks have been declining too. Thus, if the supply of credit from small banks diminishes, the economy may suffer. New businesses that want to hire workers may not be able to do so. And employees of existing small businesses, who represent more than half of private-sector workers, could lose their jobs or have their hours cut back.

Of course, the recent shrinkage of loans under $1 million at small banks appears to be at least partially due to falling demand for such loans, not just falling supply. The National Federation of Independent Business reports that about 25% of the small businesses it surveys cite poor sales as their main business problem. In contrast, only 8% report that they can’t get all the credit they need (Dunkelberg and Wade 2011).

In addition, if the pace of loan write-downs has increased, then declines in the stock of outstanding loans overstate the drop-off in new lending. Finally, the decline in outstanding business loans under $1 million at small banks is due in part to acquisitions of such banks by larger institutions. Still, aggregate business loans under $1 million are dwindling even among small banks that operated continuously throughout the study period.

Small bank health and lending

A previous Economic Letter (Laderman and Gillan 2011) explored possible links between recent trends in the estimated aggregate nonperforming ratios of business loans under $1 million at small banks and trends in the growth of the total outstanding value of such loans at these institutions. Here I relate business loan growth to a bank’s overall financial health. Supervisors judge bank financial health by taking into account capital adequacy, asset quality, management quality, earnings, liquidity, and sensitivity to market risk. Each bank is assigned a rating from 1 for the strongest to 5 for the weakest. Banks rated 1 or 2 are classified here as strong, and those rated 3, 4, or 5 as weak. The sample is the 5,453 U.S. banks with assets under $1 billion in the second quarter of 2008 that did not combine with another bank and were still operating in the fourth quarter of 2011.

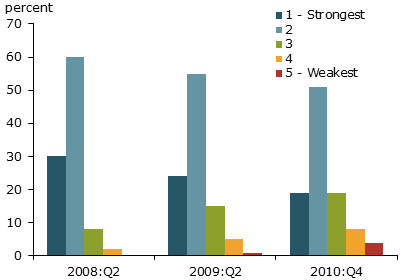

Figure 1

Distribution of small banks by supervisory rating

Not surprisingly, the financial condition of these banks deteriorated from the second quarter of 2008 to the second quarter of 2009, the last year of the recent recession. Figure 1 shows that, over that period, the proportion of weak banks increased to about 21% from about 10%. Between the end of the recession and the fourth quarter of 2010, the beginning of my most recent loan growth sample period, the proportion of weak banks further increased to about 31%.

Business loans under $1 million are categorized as commercial and industrial (C&I) or commercial real estate (CRE) if they are secured by real property. Persistent deterioration in the performance of CRE loans under $1 million at small banks (see Laderman and Gillan 2011) probably contributed to the increasing proportion of weak banks. In aggregate, CRE loans make up about 60% of the dollar volume of business loans under $1 million at small banks.

The importance of CRE lending is highlighted in an in-depth study of a small group of community banks in the eastern United States, which found that one of the most important indicators associated with an individual bank maintaining a strong financial rating between 2007 and 2010 was a relatively low ratio of CRE loans to total loans (Brastow et al. 2012). However, the intensity of CRE lending was not the only factor cited. For example, community banks that stayed strong also tended to depend less on non-core deposit funding. These consistently healthy banks also said they took great care and spent significant time underwriting loans and monitoring credit quality.

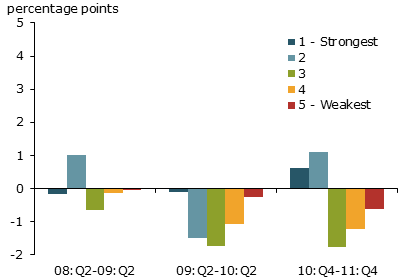

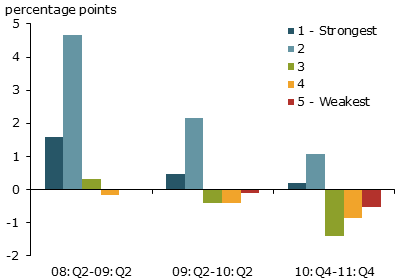

Figure 2

Loan growth at small banks by supervisory ratings

A. Small commercial and industrial loans

B. Small commercial real estate loans

Panels A and B of Figure 2 break down aggregate growth of C&I and CRE loans under $1 million at small banks according to supervisory rating for three time periods: the four quarters ending in the second quarter of 2009; the four quarters ending in the second quarter of 2010; and the full calendar year 2011. The lengths and directions of each of the bars in the two panels depend on the numbers and sizes of the banks in each rating group, as well as individual bank loan growth rates. The aggregate growth rate is the sum of the percentage points represented by each of the five bars in a given time period. For example, in 2011, rating groups 1 through 5 contributed 0.6, 1.1, –1.8, –1.2, and –0.6 percentage points respectively to the overall decline of 1.9% in C&I loans under $1 million (see panel A).

The evidence shows that, during the financial crisis and into the recovery, both C&I loans and CRE loans under $1 million shrank at weak small banks. In addition, for C&I loans in all three time periods displayed and for CRE loans in the two most recent time periods, the shrinkage of loans in these categories was disproportionately large at weak small banks. For example, about a third of small banks were in weak financial condition at the end of 2010. But, as a group, these banks accounted for more than the total decline of C&I and CRE loans under $1 million during 2011. At strong small banks, C&I and CRE loans under $1 million actually grew in 2011.

Demand for C&I loans under $1 million may be picking up. The growth of these loans at strong banks in the most recent study period marks a change from the period between the second quarter of 2009 and the second quarter of 2010. In this earlier period, even strong banks contributed to an overall decline in C&I loans under $1 million. Even excluding banks that were downgraded to weak between the second quarter of 2009 and the fourth quarter of 2010, strong small banks contributed to the 2009-to-2010 decline in C&I loans under $1 million. Subdued demand for C&I loans may have pulled down even strong bank loan volumes in the earlier period. Their increase in the later period may signal some rejuvenation.

However, even if demand for C&I loans under $1 million at small banks is gaining some traction, supply constraints among the weak banks may be impeding loan growth. Whether we soon see net growth in C&I loans under $1 million at small banks will depend on the balance between demand and supply factors. Meanwhile, panel B of Figure 2 shows continuous deceleration in the growth of CRE loans under $1 million at strong small banks from the first through the third periods. The falloff likely is related to persistent weakness in the real estate sector.

Conclusion

Small bank portfolios of business loans under $1 million are shrinking. Financially weak small banks have disproportionately accounted for this decline. At strong small banks, these loans are growing. While the recent increase of C&I loans under $1 million at strong banks may signal a turnaround in demand, the drag on supply among weak banks is likely restraining growth.

References

Brastow, Ray, Bob Carpenter, Susan Maxey, and Mike Riddle. 2012. “Weathering the Storm: A Case Study of Healthy Fifth District State Member Banks Over the Recent Downturn.” FRB Richmond S&R Perspectives Newsletter, Summer.

Dunkelberg, William C., and Holly Wade. 2011. “NFIB Small Business Economic Trends.” National Federation of Independent Business, June.

Laderman, Elizabeth, and James Gillan. 2011. “Recent Trends in Small Business Lending.” FRBSF Economic Letter 2011-32 (October 17).

Mach, Traci L., and John D. Wolken. 2006. “Financial Services Used by Small Businesses: Evidence from the 2003 Survey of Small Business Finance.” Federal Reserve Bulletin, October.

Opinions expressed in FRBSF Economic Letter do not necessarily reflect the views of the management of the Federal Reserve Bank of San Francisco or of the Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System. This publication is edited by Anita Todd and Karen Barnes. Permission to reprint portions of articles or whole articles must be obtained in writing. Please send editorial comments and requests for reprint permission to research.library@sf.frb.org