The Federal Reserve has indicated that it may raise the federal funds rate from its current value near zero in 2015. This forward policy guidance is broadly consistent with expectations from business surveys on the most likely timing for the funds rate liftoff. It also appears in line with estimates of policy liftoff from forward interest rates derived from Treasury yields. However, in interpreting forward rates, it is important to account for the zero lower bound on interest rates.

In December 2008—in the midst of a deepening recession—the Federal Reserve lowered the federal funds rate, its

traditional tool for monetary policy, to essentially its zero lower bound. Especially recently, a persistent question

has been when this key overnight policy rate will be raised. The timing of the initial increase depends critically on

the strength of the recovery and the behavior of inflation, so predicting this so-called liftoff requires forecasts of

macroeconomic conditions. Conversely, medium- and longer-term interest rates are determined in part by expectations of

the future policy rate. Thus, changes in the expected liftoff date affect a wide range of current interest rates and

financial conditions. These, in turn, alter household and business spending decisions and the pace of economic growth.

Consequently, gauging the expected timing of the funds rate liftoff is of keen interest to both policymakers and the

public. The Federal Reserve’s policymaking body, the Federal Open Market Committee (FOMC), has described its

expectations of the timing of that liftoff and the prevailing macroeconomic conditions. The FOMC also has provided

numerical forecasts of the appropriate path for the federal funds rate after it rises above its lower bound. If these

communications, part of the FOMC’s unconventional monetary policy known as forward policy guidance, can help align the

public’s expectations of future policy with policymakers’ views, then it may help monetary policy be more effective

(Rudebusch and Williams 2008). Furthermore, this forward guidance is likely to be especially valuable now, when the

federal funds rate is constrained by the zero lower bound.

To assess the effects of forward policy guidance, we first must gauge the public’s expectations about future policy

liftoff. This Economic Letter considers measures of these expectations from two sources: surveys of business

economists and forward interest rates derived from Treasury yields. However, we caution that forward rates cannot be

used without some adjustment because they can be misleading near the zero lower bound. That is, because interest rates

generally do not drop below zero, the distribution of expected future interest rates is asymmetrical. To account for

this asymmetry, we calculate liftoff expectations from Treasury yields using models that respect the lower bound and

incorporate macroeconomic information. Interpreted correctly, both the survey and market measures of policy liftoff

appear generally consistent with the FOMC’s formal guidance.

FOMC guidance on policy liftoff

Since the federal funds rate was lowered to essentially zero, the FOMC has provided explicit guidance about the

future path of the funds rate. Recent FOMC statements indicate that the Committee intends to hold the federal funds

rate near zero at least until the unemployment rate falls below 6.5%—provided that near-term inflation forecasts do

not exceed 2.5% and long-term inflation expectations remain well-anchored. This FOMC communication explicitly ties the

likely future path of the policy rate to numerical measures of economic outcomes.

The FOMC also releases information about when it expects to begin raising the policy rate in its “Summary of Economic

Projections,” which includes numerical economic forecasts from the FOMC participants. At the September 2013 FOMC

meeting, 12 of the 17 participants chose 2015 as the appropriate year for the first policy rate increase. Only three

participants preferred an earlier liftoff in 2014, and two participants viewed a later liftoff in 2016 as more

appropriate.

Liftoff expectations from surveys

Past research suggests that the FOMC forward policy guidance has influenced public expectations about future policy

(Campbell et al. 2012). Given the importance of the latest FOMC communications about liftoff, it is natural to ask

whether the FOMC’s views line up with expectations from surveys. In the September 2013 Blue Chip Economic Indicators

survey of business economists, the consensus unemployment rate forecast for the fourth quarter of 2014 was 6.8%. A

simple extrapolation of the survey’s forecast path suggests that the unemployment rate should drop below the FOMC’s

6.5% threshold around the middle of 2015. These business economists further indicated that the third quarter of 2015

is the most likely time for liftoff. Additional surveys of private-sector economists conducted by the Wall Street

Journal, Bloomberg, and others paint a similar picture of liftoff expectations.

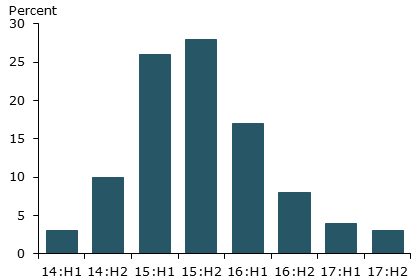

Figure 1

Distribution of primary dealers’ expected liftoff dates

A useful survey that contains more detailed information about monetary policy expectations is the Survey of Primary

Dealers, which is conducted by the Federal Reserve Bank of New York. This survey polls Wall Street economists, whose

views are likely a good reflection of the expectations of financial market participants more broadly. In the September

2013 survey, the respondents indicated that the third quarter of 2015 is the most likely quarter for liftoff.

Interestingly, the survey also reports the economists’ views on the distribution of liftoff, namely, the likelihood of

a policy liftoff occurring at a variety of different dates. Figure 1 displays these probabilities for each half-year,

ranging from the first half of 2014 to the second half of 2017. While 2015 is viewed as the most likely year for

liftoff, responses also acknowledged a significant chance of an earlier or later liftoff.

Taken together, the various surveys appear consistent with the FOMC’s forward guidance. Furthermore, Figure 1 shows

that some uncertainty regarding liftoff remains, presumably reflecting in large part that future policy actions depend

heavily on incoming data, as emphasized by the FOMC.

Liftoff expectations from the yield curve

Interest rates also contain information about the liftoff horizon expected by financial market participants. All else

equal, a more distant liftoff pushes down the average expected path of the federal funds rate and implies lower

interest rates. Of course, all else is usually not equal. In particular, interest rates also contain a premium to

compensate investors for taking on the risk of investing their money in an asset of uncertain future value. This risk

premium weakens the link between funds rate expectations and interest rates. However, the risk premium tends to be

small at shorter horizons, so interest rates of shorter maturities should provide fairly reliable readings on the

timing of a liftoff even ignoring the risk premium.

How can we infer the timing of liftoff from interest rates? Assuming a negligible risk premium, forward rates derived

from Treasury yields would exactly reflect the expected future value of the policy rate across different horizons. One

might then be inclined to estimate liftoff as the horizon when forward rates first exceed a certain threshold near

zero, say 0.25 percentage point. However, this approach ignores the fact that near zero, the expected value is not

equal to the most likely value, known in statistics as the “modal” value, of the future policy rate. Because the

policy rate cannot drop below zero, the distribution of future policy rates is very asymmetric, and the mean, or

expected value, is generally higher than the mode, or most likely value, of this distribution. As a result, the

approach we just described will generally underestimate the time until liftoff given by the FOMC or business surveys,

which report modal forecasts.

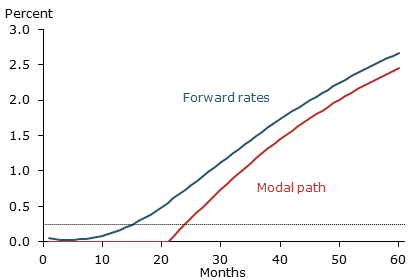

Figure 2

Forward rates and modal path in May 2013

A more accurate way to estimate liftoff from the yield curve is to use the modal path for the policy rate, which

represents its most likely outcome across horizons. To find the modal path we use a statistical model for the yield

curve and incorporate information from both yields and macroeconomic data (Bauer and Rudebusch 2013). We can estimate

the liftoff horizon simply and accurately using the modal path based on our model, and we find that our estimates are

statistically close to optimal.

To illustrate the difference between the two market-based approaches we’ve described, Figure 2 displays the path of

forward rates and the modal path at the end of May 2013. The horizontal line at 0.25 percent corresponds to the upper

level of the target range that the FOMC has set for the federal funds rate. The measure based on forward rates first

crosses this threshold at 16 months, which corresponds to estimated liftoff in September 2014. By contrast, the modal

path crosses the threshold much later, at a horizon of 25 months, which would put liftoff at June 2015. In general,

the liftoff calculated from forward rates is always earlier than the liftoff estimated from the modal path. In this

particular case, the estimate based on the modal path is much more plausible, more closely matching the forecasts of

survey participants and policymakers.

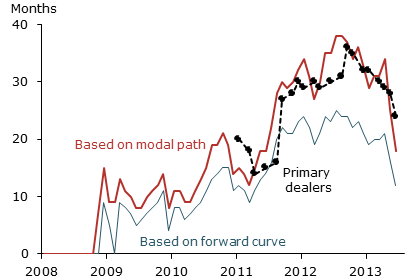

Figure 3

Alternative estimates of time until policy liftoff

To compare alternative measures of the liftoff horizon over time, Figure 3 plots three estimates starting in 2008 and

ending in June 2013. Our preferred estimates based on the modal path (thick red line) track the expectations from the

Survey of Primary Dealers (black dotted line) quite closely. The estimates based on forward rates (thin blue line) are

typically lower than the other two measures, and show a larger discrepancy in 2012 and early 2013 when interest rates

were particularly low and the asymmetry described earlier was very pronounced.

An interesting feature of the liftoff estimates in Figure 3 is their increase in mid-2011. Around that time, forward

guidance by the FOMC pushed out the public’s expectations for funds rate liftoff (Swanson and Williams 2012). Our

estimates based on the modal path show that the liftoff horizon increased further until late 2012, in line with the

weakness of the recovery and increasing downside risks to the economic outlook at the time. Beginning in late 2012,

the estimated liftoff horizon decreased, due to both the passage of time and more upbeat economic data. The most

recent data in the figure show that the market-based estimates for the liftoff horizon fell more than the survey-based

horizon. During this recent episode, interest rates increased substantially, likely because various market dynamics

amplified more limited moves in expectations about monetary policy.

Conclusion

When interpreting interest rates to learn how soon markets expect the Federal Reserve to begin raising its policy

rate, it is important to avoid misleading results. Instead of considering the first horizon when forward rates exceed

the threshold for liftoff, one should focus on when the modal path—that is, the most likely path—of the policy rate

crosses the threshold. Otherwise the pronounced asymmetry of interest rates, which is a fundamental characteristic of

the zero lower bound environment, is ignored. An estimated modal path can be obtained from statistical models of the

yield curve, which is the approach we pursue here, or alternatively from prices of interest rate options (see Malz

2013).

While market-based measures of liftoff can be affected by various factors that cause interest rate volatility, these

measures are generally in line with survey-based estimates. Our estimates suggest that the FOMC’s forward guidance has

been effective in pushing out the expected liftoff horizon, which has contributed to lower interest rates, easing

financial conditions and adding stimulus to the economy. Recent estimates of policy liftoff generally suggest the

first funds rate hike will occur sometime in 2015.

Michael D. Bauer is an economist in the Economic Research

Department of the Federal Reserve Bank of San Francisco.

Glenn D. Rudebusch is director of economic research and executive vice president in the Economic Research Department

of the Federal Reserve Bank of San Francisco.

References

Bauer, Michael D., and Glenn D. Rudebusch, 2013. “Monetary Policy Expectations at the Zero

Lower Bound.” FRB San Francisco Working Paper 2013-18.

Campbell, Jeffrey, Charles Evans, Jonas Fisher, and Alejandro Justiniano. 2012. “Macroeconomic Effects of

Federal Reserve Forward Guidance.” Brookings Papers on Economic Activity, Spring.

Malz, Allan. 2013. “Implied

Rate Correlations and Policy Expectations.” FRBSF Economic Letter 2013-32 (November 4).

Rudebusch, Glenn D., and John C. Williams. 2008. “Revealing the Secrets of the Temple: The Value of

Publishing Central Bank Interest Rate Projections.” In Asset Prices and Monetary Policy, ed. J.Y.

Campbell. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, pp. 247–284,

Swanson, Eric T., and John C. Williams. 2012. “Measuring the Effect of the Zero Lower

Bound on Medium-and Longer-Term Interest Rates.” FRB San Francisco Working Paper 2012-02.

Opinions expressed in FRBSF Economic Letter do not necessarily reflect the views of the management of the Federal Reserve Bank of San Francisco or of the Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System. This publication is edited by Anita Todd and Karen Barnes. Permission to reprint portions of articles or whole articles must be obtained in writing. Please send editorial comments and requests for reprint permission to research.library@sf.frb.org