In the wake of the financial crisis, the Federal Reserve dropped the federal funds rate to near zero to bolster the U.S. economy. Recent research suggests that the constraint preventing this rate from being even lower has kept the economy from reaching its full potential. Given the lingering economic slack, allowing inflation to rise temporarily above the Fed’s 2% target might help achieve a better balance between the Fed’s dual mandates of maximum employment and stable prices more quickly.

The Federal Reserve responded aggressively to the most recent financial crisis by cutting the target for its benchmark short-term interest rate, known as the federal funds rate, to its effective zero lower bound in December 2008, where it stayed until the end of last year. Shortly afterward, the Fed began providing information about the probable future path of the short-term interest rate, a policy that became known as forward guidance. The Fed also bought large quantities of asset-backed securities and long-term U.S. Treasuries, a policy known as quantitative easing. This policy mix was successful in significantly lowering the unemployment rate from its high of nearly 10% in 2010 to around 5% now.

Yet, despite the stimulus provided by this policy mix, some economic slack remains, and the inflation rate continues to run below the Federal Reserve’s long-term target of 2%. Given this environment, several commentators have discussed whether allowing inflation to rise temporarily above the 2% target might be prudent to achieve the Fed’s dual mandate more rapidly.

In this Economic Letter I consider whether inflation overshooting would be suitable under current circumstances. Model estimates suggest that allowing inflation to reach nearly half a percentage point above target temporarily would eliminate the remaining economic slack by the end of the present year, substantially faster than if inflation remained below its target. Thus, it could achieve a better balance between the Federal Reserve’s mandates of stable prices and maximum employment sooner. My analysis further shows that inflation overshooting is desirable due to the constraint that the zero lower bound on the federal funds rate has imposed on monetary policy in recent years.

A theoretical argument for inflation overshooting

Standard monetary theory states that the short-term nominal interest rate should be lowered to stimulate the economy whenever there is low inflation or economic slack—that is, when economic resources are not being fully used to their most efficient level. However, the nominal interest rate has a lower bound that is typically around zero. In theory, Eggertsson and Woodford (2003) showed that when the zero lower bound is binding, it is desirable to allow inflation to overshoot its target to promote a faster recovery in real economic activity.

At the heart of the Eggertsson-Woodford argument is the idea that economic slack increases with the real interest rate, which is the nominal short-term interest rate minus the expected future inflation rate. If prices and wages were able to adjust to economic conditions instantaneously then the economy would operate at its efficient level and there would be no economic slack. However, in normal conditions, prices and wages take some time to respond to changes in economic conditions, which leads to economic resources being underutilized. If this so-called economic slack is substantial—for example, following a financial crisis that restricts credit and pushes down consumption and investment spending—then according to the normal policy prescription policymakers would lower the short-term nominal interest rate. In turn, this would bring down the short-term real interest rate to stimulate the economy and reduce the slack.

However, this policy prescription becomes ineffective if the nominal interest rate is at the zero lower bound. Because of this constraint, policymakers cannot engineer a decline in the short-term real interest rate to stabilize economic activity, and economic slack ends up larger than it would otherwise be. In other words, the real interest rate would still be too high. To make matters worse, elevated economic slack puts downward pressure on inflation and inflation expectations, which pushes the real interest rate up further, triggering even more slack.

Despite the zero lower bound, policymakers can still bring about a lower short-term real interest rate if they can generate higher inflation expectations. One way to do this is by communicating that the central bank intends to keep the nominal short-term interest rate low for longer than would otherwise be dictated by economic conditions; this has been a motivation behind the Federal Reserve’s forward guidance policy in recent years. Expecting a more expansionary monetary policy in the future should help boost future inflation and thus raise current inflation expectations, translating into a lower real short-term interest rate. Taking this theory a step further, by allowing future inflation to temporarily rise above target, the central bank can bring about a greater decline in the real interest rate and stabilize economic activity faster.

Estimating the degree of overshooting

I use the empirical model described in Cúrdia et al. (2015) to evaluate whether the Eggertsson-Woodford argument motivates inflation overshooting under current economic conditions and, if so, by how much. In my model, economic slack increases with the real interest rate, as in the Eggertsson and Woodford model. Slack also depends on several other factors, such as government spending, tight financial conditions that restrict households and firms from borrowing, and labor productivity. In this model, inflationary pressures fall with economic slack, but rise with expected future inflation and a cost-push shock, like a change in oil supply that affects the price of production inputs. I also incorporate the effects of forward guidance in the model. This setup allows me to generate forecasts that account for the zero lower bound of the federal funds rate.

I use the model to forecast the evolution of inflation. In particular, I consider the forecast based on optimal control, in which the federal funds rate is set in order to achieve the best possible balance between multiple goals: stabilizing both inflation around its target and output around its potential path, while avoiding excessive federal funds rate volatility. For comparison, I also develop a forecast under an estimated monetary policy rule, in which the federal funds rate increases with inflation deviations from target and economic slack.

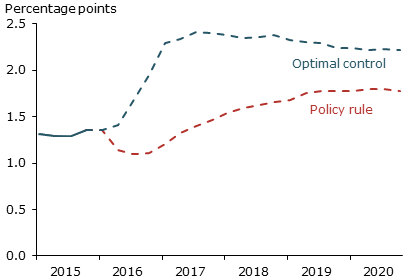

The forecasts are based on data from 1987 through the fourth quarter of 2015 for core personal consumption expenditures price inflation, real GDP growth, the effective federal funds rate, and the 10-year median expected inflation from the Survey of Professional Forecasters. Figure 1 shows the projected path for the four-quarter change in inflation from the first quarter of 2016 up to the last quarter of 2020. The dashed red line is the median forecast under the policy rule and the dashed blue line is the median forecast under optimal control.

Figure 1

Median projections for core PCE price inflation

Note: Model-based median projections of four-quarter change in

core personal consumption expenditures (PCE) price inflation.

Figure 1 shows that, under optimal control, inflation reaches as much as 0.4 percentage point above target and remains above 2% through 2020. Thus, this model suggests that current economic conditions warrant a policy that tolerates higher inflation in the near future to speed up the ongoing economic recovery. Indeed all of the current economic slack is eliminated by the end of the current year. By contrast, under the policy rule it would take until the end of the forecast horizon to achieve the same improvement. In that case, inflation would instead gradually increase toward target—a pace that reflects the gradual reduction in economic slack induced by the financial crisis.

What explains inflation overshooting in the model?

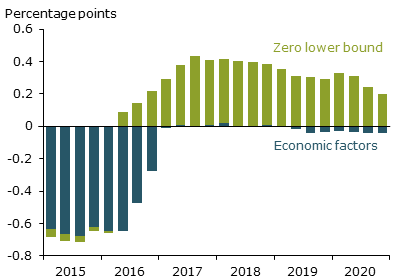

To better understand why inflation overshooting is optimal in this model, I separate the projected path of inflation into its drivers. In particular, I distinguish between fundamental economic factors—for instance, various changes in productivity and demand—and the effects of a binding zero lower bound on the federal funds rate. Figure 2 shows how much these two components contribute each quarter to inflation deviations from target under optimal control during the forecast period. The blue bars measure the contribution of fundamental economic factors, and the green bars represent the contribution of the zero lower bound.

Figure 2

Inflation drivers under optimal control (annualized)

Figure 2 shows that fundamental economic factors are not projected to have any substantial effects on inflation after 2016 under optimal control. Instead, the boost to inflation is nearly fully explained by the effects of the zero lower bound, in line with the Eggertsson-Woodford argument. This means that the reason inflation overshooting is desirable is not directly due to the effects of recent oil price shocks or the financial crisis per se. Instead, overshooting is warranted because the effects of the financial crisis were so severe that the zero lower bound became a substantial constraint on monetary policy.

Other considerations

In addition to recovering from the effects of the zero lower bound, there are other arguments for inflation overshooting. One is the longer-term effects of higher unemployment. Persistently high unemployment rates may lead to skill depreciation and make it harder for unemployed workers to find jobs, possibly resulting in a permanently higher natural rate of unemployment. Overshooting inflation could speed up the recovery in the labor market and prevent these long-term effects. Other arguments highlight how different speeds of recovery in various segments of the labor market can make it advantageous to have higher inflation in order to achieve a faster recovery in the labor market as a whole. Erceg and Levin (2014) discuss the benefit of inflation overshooting to increase the employment-to-population ratio, which has declined substantially since the financial crisis. Rudebusch and Williams (2015) focus on the distinction between short- and long-term unemployment and highlight that inflation overshooting would hasten the decline in the number of long-term unemployed.

Of course, there are arguments against inflation overshooting as well. The classic one is that if inflation remains above target for too long, it could cause inflation expectations to become unanchored. This could lead the Federal Reserve to lose credibility, and make it harder to stabilize inflation and economic activity in the future. Alternatively, we may also be mismeasuring the degree of economic slack. In particular, there would be less need for inflation overshooting if there were less slack than is estimated in the model economy.

Conclusion

This Letter evaluates whether inflation overshooting in the near future could be a good thing for the economic recovery. The analysis suggests that there is a case for allowing inflation to remain above target in the near term given current conditions. According to model estimates, the constraint of the zero lower bound on monetary policy has helped drive up the amount of economic slack. This makes it desirable to trade some future above-target inflation for a faster recovery in economic activity.

Vasco Cúrdia is a research advisor in the Economic Research Department of the Federal Reserve Bank of San Francisco.

References

Cúrdia, Vasco. 2014. “The Risks to the Inflation Outlook.” FRBSF Economic Letter 2014-34 (November 17).

Cúrdia, Vasco, Andrea Ferrero, Ging Cee Ng, and Andrea Tambalotti. 2015. “Has U.S. Monetary Policy Tracked the Efficient Interest Rate?” Journal of Monetary Economics 70, pp. 72–83.

Eggertsson, Gauti B. and Michael Woodford. 2003. “The Zero Bound on Interest Rates and Optimal Monetary Policy.” Brookings Papers on Economic Activity 34(1), pp. 139–211.

Erceg, Christopher J., and Andrew T. Levin. 2014. “Labor Force Participation and Monetary Policy in the Wake of the Great Recession.” Journal of Money, Credit, and Banking 46(S2, October), pp. 3–49.

Rudebusch, Glenn D., and John C. Williams. 2015. “A Wedge in the Dual Mandate: Monetary Policy and Long-Term Unemployment.” Journal of Macroeconomics (article in press, May 20).

Opinions expressed in FRBSF Economic Letter do not necessarily reflect the views of the management of the Federal Reserve Bank of San Francisco or of the Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System. This publication is edited by Anita Todd and Karen Barnes. Permission to reprint portions of articles or whole articles must be obtained in writing. Please send editorial comments and requests for reprint permission to research.library@sf.frb.org