Great question. Unfortunately, there isn’t a standard answer, although there is a well-known joke economists like to tell regarding the difference between the two. But, let’s come back to that later.

Recession

Let’s start by defining a recession. As I mentioned, there are several commonly used definitions of a recession. For example, journalists often describe a recession as two consecutive quarters of declines in quarterly real (inflation adjusted) gross domestic product (GDP).

The definition used by economists differs. Economists use monthly business cycle peaks and troughs designated by the National Bureau of Economic Research (NBER) to define periods of expansion and contractions. The NBER website lists the peaks and troughs in economic activity starting with the December 1854 trough. The website also defines a recession as:

A recession is a significant decline in economic activity spread across the economy, lasting more than a few months, normally visible in real GDP, real income, employment, industrial production, and wholesale-retail sales. A recession begins just after the economy reaches a peak of activity and ends as the economy reaches its trough. Between trough and peak, the economy is in an expansion. Expansion is the normal state of the economy; most recessions are brief and they have been rare in recent decades.

Depression

While there is also no standard definition for depression, it is commonly defined as a more severe version of a recession. In his popular intermediate macroeconomics textbook, Gregory Mankiw (Mankiw 2003) distinguishes between the two:

There are repeated periods during which real GDP falls, the most dramatic instance being the early 1930s. Such periods are called recessions if they are mild and depressions if they are more severe.

As Mankiw pointed out, perhaps the most famous economic downturn in the U.S.’s (as well as the world’s) economic history was the Great Depression, often described as starting in 1929 and lasting at least through the 1930s and into the early 1940s, a period that actually includes two severe economic downturns. Using the NBER business cycle dates, the first downturn of the Great Depression started in August 1929 and lasted 43 months, until March 1933, far longer than any other twentieth century contraction. The economy then expanded for 21 months, from March 1933 until May 1937, before suffering another downturn: from May 1937 until June 1938, a period of 13 months, the economy again contracted.

Degree of Severity

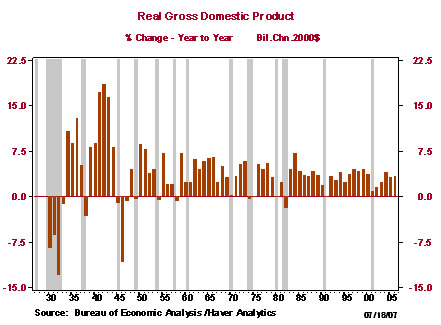

One quick way to illustrate the difference between the severities of the economic contractions associated with recessions over the period from 1930 to 2006 is to examine the annual growth rates of real GDP (in chained year 2000 dollars). Chart 1 shows the annual growth or contraction in the economy. The gray bars represent recessions identified by the NBER. The two most severe contractions in output (excluding the post-World War II adjustment from 1945 to 1947) occurred during the Great Depression of the 1930s.

Chart 1: Annual growth rate of Real GDP (%)

In a March 2, 2004, speech at Washington and Lee University, then Governor, and now Fed Chairman, Ben Bernanke, contrasted the severity of the initial downturn during the Great Depression and the most severe post-World War II recession of 1973-1975. The differences are telling:

During the major contraction phase of the Depression, between 1929 and 1933, real output in the United States fell nearly 30 percent. During the same period, according to retrospective studies, the unemployment rate rose from about 3 percent to nearly 25 percent, and many of those lucky enough to have a job were able to work only part-time. For comparison, between 1973 and 1975, in what was perhaps the most severe U.S. recession of the World War II era, real output fell 3.4 percent and the unemployment rate rose from about 4 percent to about 9 percent. Other features of the 1929-33 decline included a sharp deflation—prices fell at a rate of nearly 10 percent per year during the early 1930s—as well as a plummeting stock market, widespread bank failures, and a rash of defaults and bankruptcies by businesses and households. The economy improved after Franklin D. Roosevelt’s inauguration in March 1933, but unemployment remained in the double digits for the rest of the decade, full recovery arriving only with the advent of World War II. Moreover, as I will discuss later, the Depression was international in scope, affecting most countries around the world not only the United States.

While you can see from the above discussion that recessions and depressions are serious business, some economists have been known to suggest that there is another more casual way to explain the difference between a recession and a depression (recall that I began this answer with a promise of a joke):

When your neighbor loses their job, it’s a recession.

When you lose your job, that’s a depression!

References

Ask Dr. Econ. May 2002. “What are business cycles and how do they affect the economy?” Federal Reserve Bank of San Francisco website.

Bernanke, Ben S. 2004. “Money, Gold, and the Great Depression” Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System, Washington, DC. March 2, 2004.

Greenwald, Douglas, Editor in Chief. The McGraw-Hill Encyclopedia of Economics. McGraw-Hill, Inc., New York, Second Edition. See Business Cycles, pages 96-104, by Geoffrey H. Moore.

Mankiw, N. Gregory. 2003. Macroeconomics. Worth Publishers, New York, Fifth Edition. See Chapter 1. page 4.

National Bureau of Economic Research (NBER)