The latest estimates of overall pandemic excess savings remaining in the U.S. economy have turned negative, suggesting that American households fully spent their pandemic-era savings as of March 2024. However, consumer spending has remained strong in recent months, which raises an important question: What’s next?

Where did the excess savings come from?

In a study last year (Abdelrahman and Oliveira 2023), we examined household saving patterns following the onset of the pandemic recession. Our study showed that households rapidly accumulated unprecedented levels of excess savings—defined as the difference between actual savings and the pre-recession trend—relative to previous recessions.

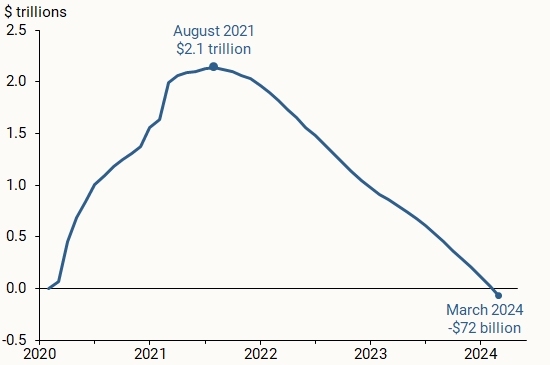

We also launched a monthly data page, “Pandemic-Era Excess Savings,” to help track how much excess savings remains in the aggregate U.S. economy. Figure 1 shows the evolution of these excess savings at the aggregate level. As of March 2024, our estimate shows that overall excess savings in the U.S. economy have been fully depleted.

Figure 1

Cumulative pandemic-era excess savings

Source: Bureau of Economic Analysis and authors’ calculations.

Excess savings were built up over a period of 18 months, from the onset of the pandemic recession in March 2020 until August 2021. The rapid accumulation was largely due to pandemic-related financial support to U.S. households and a steep decline in consumer spending as a result of health-related social distancing and business closures.

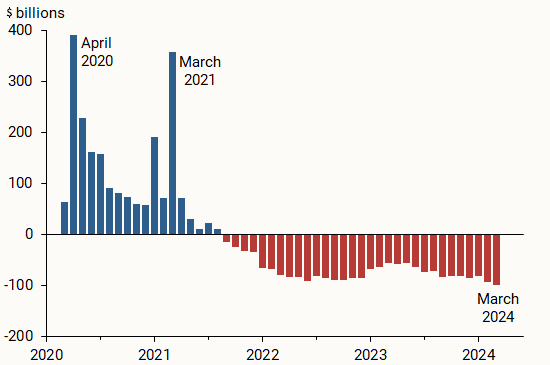

We estimate that excess savings at the aggregate level peaked at $2.1 trillion in August 2021 and were steadily depleted over the subsequent 2½ years. Households drew down their excess savings at an average pace of $70 billion per month since September 2021, although this drawdown accelerated to about $85 billion per month since last fall relative to the average pace for the entire period. Figure 2 shows this monthly accumulation, in blue, and subsequent drawdown, in red, of pandemic-era excess savings.

Figure 2

Monthly change in cumulative excess savings

Source: Bureau of Economic Analysis and authors’ calculations.

What will this mean for U.S. consumers?

Consumer spending is a key driver of U.S. economic growth, and it has been robust over the past two years. Household demand for goods and services has remained surprisingly resilient in the face of rising or high interest rates as well as elevated—albeit falling—inflation. With our estimate of excess savings dropping below zero, what does this mean for the future of U.S. households and consumer spending?

While the large stock of excess savings that was accumulated in 2020 and 2021 played a role in supporting the overall financial health of American households, it was only one of many possible factors that helped consumers maintain robust spending levels. For example, the U.S. labor market has been very strong over the past few years. The unemployment rate has dropped to near-historic lows, employment levels are at an all-time high, wages have grown beyond historical averages, and monthly job gains have regularly exceeded 200,000. A continuing strong labor market could help consumers maintain spending patterns similar to those observed recently, even without pandemic-era savings.

Consumers could use their non-pandemic-related savings as another source of funding for their household consumption. Many households saw notable gains in their equity and other asset holdings over the past year (Abdelrahman, Oliveria, and Shapiro 2024). Also, households across the income distribution now own notably more nonfinancial assets, such as real estate holdings and vehicles, relative to pre-pandemic levels, according to Distributional Financial Accounts data from the Federal Reserve Board. To the extent that households are able to access funding from these less liquid assets, consumer spending could continue at a robust pace going forward. Finally, consumers could use debt—such as credit cards and personal loans—to further support their current spending habits, although the current elevated interest rate environment means that the cost of using credit is higher than in the decade preceding the pandemic recession.

Uncertainty and final thoughts

Estimates of aggregate excess savings during the pandemic period are filled with uncertainty because they are highly sensitive to the methodology used and the assumptions made about the pre-pandemic trend. Overall, despite differing methodologies and assumptions, much of the existing research on household savings following the pandemic recession points to a rapid accumulation and more gradual drawdown of excess savings in the United States. Our estimates suggest that pandemic-era savings have been fully spent at the aggregate level.

The path of consumer spending in the United States is difficult to forecast with any degree of accuracy. Nevertheless, the depletion of these excess savings is unlikely to result in American households sharply cutting their spending levels as long as they are able to support their consumption habits through continuous employment or wage gains, other forms of wealth—including non-pandemic-related savings—and higher debt.

References

Abdelrahman, Hamza, and Luiz E. Oliveira. 2023. “The Rise and Fall of Pandemic Excess Savings.” FRBSF Economic Letter 2023-11 (May 8).

Abdelrahman, Hamza, Luiz E. Oliveira, and Adam Shapiro. 2024. “The Rise and Fall of Pandemic Excess Wealth.” FRBSF Economic Letter 2024-06 (February 26).

The views expressed here do not necessarily reflect the views of the management of the Federal Reserve Bank of San Francisco or of the Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System.