The U.S. economy has remained remarkably resilient this year, navigating uncertainty, changes in government policy, including tariffs, immigration, deregulation, and taxes, an AI-driven technology surge, and modestly restrictive monetary policy. At the same time, inflation, subtracting the impact of tariffs on goods prices, has gradually declined, although it remains elevated. This is all good news and reflects the economy’s underlying strength and our ongoing progress in restoring price stability.

But the balance of risks has clearly shifted, as the labor market has rapidly softened and inflation has risen less than many projected earlier in the year. The Federal Open Market Committee (FOMC) appropriately reduced the policy rate—by a total of 50 basis points this year—as part of prudent risk management. These adjustments provide needed insurance for the labor market, while maintaining a modestly restrictive policy stance to further reduce inflation.

The question is: Will more be needed? Here’s how I think about it.

The economy is being buffeted by both cyclical and secular forces. In real time, it can be hard to know which will have the larger impact.

But we can get a lot of clarity by looking at the basics: supply, demand, and prices.

Let’s start with the labor market. Clearly, there has been a secular change in labor supply related to declines in immigration.1 The shift in labor supply has been significant, with trend labor force growth falling from around 150,000 per month in early 2024 to roughly 50,000 per month in the first half of 2025.2 Up to now, this has been met nearly one-for-one with changes in available jobs, leaving the unemployment rate relatively steady.

The question is whether the drop in job availability has been a reaction to falling supply or an independent decline in labor demand. Said differently, is the slowdown in payroll employment growth the result of a negative supply shock (secular) or a negative demand shock (cyclical)?

Wage movements reveal the answer. Nominal and real wage growth have slowed overall as the labor market has cooled,3 even in many sectors where foreign-born workers were a larger share of employment. If the slowing in payroll employment growth was mostly structural, related to labor supply, the opposite would be true: Wage growth would rise, especially in the sectors most directly affected by changes in immigration. The bottom line: We are likely experiencing a negative demand shock. Demand for workers has fallen4 —it just happened to be met with a nearly coincident decline in the labor supply.

Turning to inflation. Restrictive monetary policy is putting downward pressure on inflation, a cyclical phenomenon. At the same time, secular changes in tariffs are working their way through to goods prices.5 But unlike what many projected, trade rebalancing has not led to more broad-based and persistent inflation dynamics.6 Indeed, so far, the effects of the tariffs have largely been confined to goods, with little spillover into services inflation or inflation expectations, which remain relatively well-anchored around our target.

But these near-term questions on the impact of immigration and tariffs are not the only ones we must grapple with. We must also consider broader, more medium-term issues about the underlying pressures on inflation and the role of technology in the evolution of productivity and the labor market. And we must ask ourselves, are we in the 1970s or the 1990s?

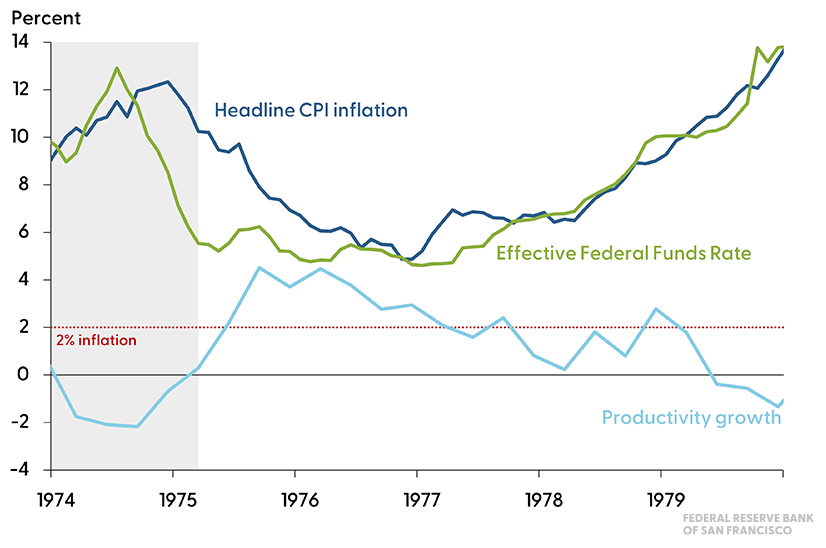

If we are in a period like the 1970s, when households and businesses were worried about higher inflation and highly reactive to price changes, then letting go of the policy reins too soon could end in a policy mistake: relaxing policy, only to find that inflation digs in and becomes harder to manage. The FOMC did exactly this back in the 1970s (Figure 1). They lowered rates, seeing a softening labor market, and missed a structural slowdown in productivity growth. Inflation and inflation expectations rose rapidly and didn’t come back down until the aggressive actions of the Volcker Fed.7 Obviously, this is a situation we want to avoid.

Figure 1.

Monetary policy, inflation, and productivity (1974-1979)

Source: Bureau of Labor Statistics and Federal Reserve Board of Governors.

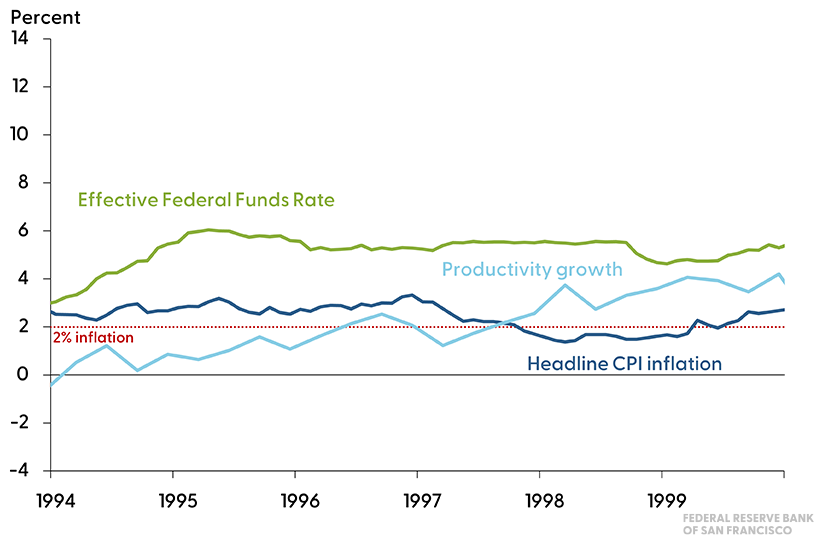

But if we are in a period like the 1990s, something different is in front of us. It was an equally challenging time for policymakers, who faced a nervous workforce, relatively low unemployment, elevated inflation, and the possibility that computers and the internet could deliver measurable productivity gains.8 The FOMC had vigorous debates about whether to react strongly to low unemployment and signs of rising inflation or take signal from emerging hints of a secular shift in productivity growth and the labor market.9 In the end, they took a balanced approach to policy, and we ended up with the roaring 90s and contained inflation (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Monetary policy, inflation, and productivity (1994-1999)

Source: Bureau of Labor Statistics and Federal Reserve Board of Governors.

So, what’s the lesson here? We can’t ignore the 1970s or the post-pandemic inflation run-up, but we can’t ignore the rest of history either. We don’t want to work so hard to not be the 1970s that we cut off the possibility of the 1990s, losing jobs and growth in the process. That would be trading one mistake for another.

Getting policy right will require an open mind and digging for evidence on both sides of the debate. Clarity is there. You just have to look for it, regardless of where it leads.

Footnotes

1. Duzhak and New-Schmidt (2025).

2. For more information, see Bengali et.al (2025).

3. For example, according to data from the Bureau of Labor Statistics, nominal average hourly earnings of private-sector employees grew by 3.7% in August on a 12-month basis, the slowest pace in over a year. When adjusted for inflation, growth in average hourly earnings was only 0.7% in August.

4. Other labor market indicators, including the job-finding rate and private-sector measures from hiring surveys and worker sentiment surveys, also point to softening labor demand.

5. Recent increases in inflation have been evident primarily in goods categories (Federal Reserve Bank of San Francisco 2025).

6. The rise in goods inflation from the new tariffs has so far not spilled over to services inflation (Leduc 2025).

7. For more information on inflation dynamics and monetary policy actions during the 1970s, see Lansing and Nucera (2023) and Orphanides and Williams (2013).

8. This period was later recognized as showing an increase in trend productivity growth (Fernald 2015).

9. See, for example, Board of Governors (1996) for discussions among policymakers about the impact of a tight labor market on inflationary pressures, and Board of Governors (1997) for discussions of the role that accelerated productivity might play in containing inflation.

References

Bengali, Leila, Ingrid Chen, Addie New-Schmidt, and Nicolas Petrosky-Nadeau. 2025. “Labor Supply and Demand Are Slowing in Tandem.” SF Fed Blog, November 6.

Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System. 1996. “Meeting of the Federal Open Market Committee, July 2-3, 1996: Transcript.”

Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System. 1997. “Meeting of the Federal Open Market Committee, May 20, 1997: Transcript.”

Duzhak, Evgeniya, and Addie New-Schmidt. 2025. “Updated Estimates of Net International Migration.” SF Fed Blog, July 17.

Federal Reserve Bank of San Francisco. 2025. “PCE Inflation Contributions from Goods and Services.” Updated September 26.

Fernald, John. 2015. “Productivity and Potential Output Before, During, and After the Great Recession.” NBER Macroeconomics Annual 29(1), pp. 1–51.

Lansing, Kevin, and Federico C. Nucera. 2023. “Inflation Expectations, the Phillips Curve, and Stock Prices.” FRBSF Economic Letter 2023-24 (September 25).

Leduc, Sylvain. 2025. “SF FedViews: October 16, 2025.” Federal Reserve Bank of San Francisco.

Orphanides, Athanasios, and John C. Williams. 2013. “Monetary Policy Mistakes and the Evolution of Inflation Expectations.” In The Great Inflation: The Rebirth of Modern Central Banking, ed. by Michael D. Bordo and Athanasios Orphanides, Chicago: University of Chicago Press, pp. 255–297.

The views expressed here do not necessarily reflect the views of the management of the Federal Reserve Bank of San Francisco or of the Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System.