Chinese authorities took a number of steps in 2015 to liberalize its financial markets. This includes the People’s Bank of China’s decision to allow the daily fixing for renminbi exchange rates to align more closely with the previous day’s closing price, the elimination of restrictions on bank deposit rates, the opening up of the onshore interbank foreign exchange market to international central banks and sovereign wealth funds, and the adoption of the International Monetary Fund’s (IMF) Special Data Dissemination Standards (SDDS) (Table 1).

Table 1: Major events in China’s financial reforms (2015)

| Date | Event |

|---|---|

| January-June 2015 | Five de novo private banks opened for business. |

| March 1, 2015 | Deposit rate ceilings are raised to 1.3x benchmark levels. |

| May 1, 2015 | Deposit Insurance Scheme came into effect. |

| May 10, 2015 | Deposit rate ceilings are raised to 1.5x benchmark levels. |

| August 11, 2015 | The PBOC devalued the yuan by roughly 2 percent, and announced that the each day’s central fixing rate will become more aligned with the previous day’s closing. |

| September 30, 2015 | Foreign central banks, sovereign wealth funds, and international agencies gained access to China’s onshore interbank foreign exchange market. |

| October 8, 2015 | The PBOC announced that China’s official statistics will conform to the IMF’s Special Data Dissemination Standards (SDDS). |

| October 8, 2015 | China launched a new Cross-border Inter-bank Payment System (CIPS). |

| October 24, 2015 | Deposit interest rates were fully liberalized. |

| November 30, 2015 | The IMF agrees to include China’s RMB as a fifth currency in its Special Drawing Rights (SDR) basket. |

| December 11, 2015 | The PBOC started to track the value of the renminbi against a basket of currencies instead of just the U.S. dollar. |

Sources: PBOC and media reports.

When the IMF decided to include the renminbi as a fifth currency in the Special Drawing Rights basket last November, the pace of China’s financial liberalization appeared to be faster and more significant than ever despite the financial market turmoil in the summer and the soft economic performance. Most of these reforms have been on the policy makers’ to-do list for decades, and there is growing sense of urgency among leaders that these reforms need to be done in order to rebalance the economy and achieve more sustainable growth.

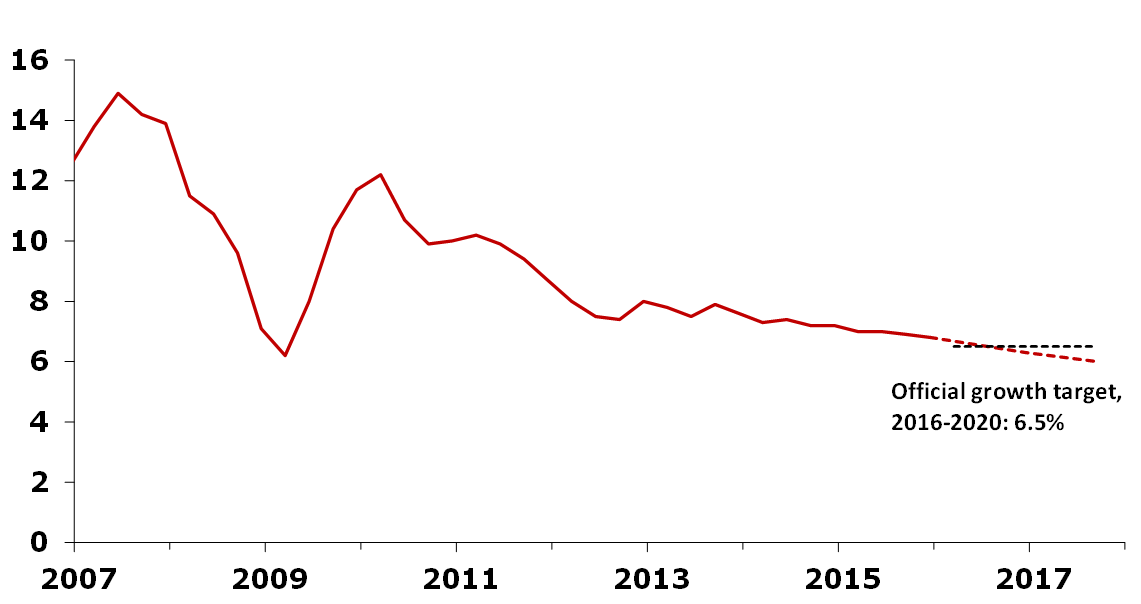

Nonetheless, with the Chinese economy experiencing a prolonged slowdown (Figure 1), it is a difficult task to strike a balance between ensuring employment and economic growth in the short-term while implementing long-term rebalancing. Major steps to reform the country’s financial markets often go hand-in-hand with some policy easing. For example, the currency devaluation last August coincided with the introduction of a more flexible exchange rate regime, and the interest rates and RRR cuts accompanied the gradual liberalization of deposit rates. It appears that the authorities wish to ensure that volatility is not excessive, and that the economy will not suffer because of these reforms.

Figure 1: China’s Q4 growth was the slowest since Q1 2009

Note: IMF forecasts after 2015.

Sources: Chinese Bureau of Statistics, IMF.

Notwithstanding this cautiousness, the markets do not always react as policymakers expect. But let’s face it, the Chinese economy, especially its private sector, has grown substantially in size and complexity over the past decade. Even without the equity market woes, China’s economic future won’t always be smooth sailing.

We should not expect that what worked in the past—generating growth through state-owned banks and state-owned enterprises—will remain effective forever. Regulators seemed to be surprised by the out-of-control equity market as well as the market (over)reaction following the PBOC’s announcement to devalue the RMB last year. Going forward, they will likely see more surprises because in a more liberalized market, market participants do not merely take cues from the authorities and instead can shape economic events themselves. In that sense, near-term volatility should be well expected as a feature, albeit a bittersweet one, of liberalization.

To fight excessive volatility amid capital outflows, financial regulators have taken some steps to dial back financial liberalization reforms. For instance, the PBOC has reportedly tightened capital controls in recent months, which is a sensible move to ensure financial stability, but have nonetheless introduced uncertainties in the future of the internationalization of the renminbi and represent a (temporary) step back in China’s pursuit of greater capital account openness.

Still, if one focuses on a longer time horizon, China is moving in the right direction. The resilience of the Chinese economy will continue to be tested in a more integrated global capital market, at a time when uncertainties are on the rise. But this is a test that is unavoidable as long as financial liberalization remains the goal of the leadership.

Meanwhile, market participants are anxious to find new policy anchors as China moves towards a “New Normal.” Last November, the State Council proposed a growth bottom line of 6.5 percent for 2016-2020. However, given the IMF’s recent economic forecast which projects that China’s economic growth will further slow to 6.3 and 6.0 percent in 2016 and 2017, respectively, more accommodative policies (and some slowdown in financial and structural reforms) may be required to reach that goal. China’s growth and policy direction are likely to be less predictable in the future, a fact that market participants will have to learn to accept.

The views expressed here do not necessarily reflect the views of the management of the Federal Reserve Bank of San Francisco or of the Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System.