China’s bond market has grown rapidly in recent years and is now the third largest in the world, behind only the United States and Japan. Historically, the domestic bond market has been largely off-limits to foreign investors due to the China’s capital controls. However, this is beginning to change as China implements new reforms to allow foreign investors greater access. At the same time, an increasing number of defaults indicate that the bond market is becoming riskier. The larger, more open, and riskier bond market is creating a host of new challenges for regulators.

Analysis of China’s bond market is complicated by its complex structure. Government bonds, financial bonds, and repos all trade in the interbank market. Corporate bonds, however, vary in both type and market. Table 1 illustrates the breakdown of types of corporate bonds in China.

Table 1 – Types of Corporate Bonds

| Type of Bond | Market | Regulator |

|---|---|---|

| Medium-Term Note | Interbank Market | People’s Bank of China (PBoC) |

| Corporate Bond | Securities Exchanges | China Securities Regulatory Commission (CSRC) |

| Enterprise Bond | Interbank Market, Securities Exchanges | National Development and Reform Commission (NDRC) |

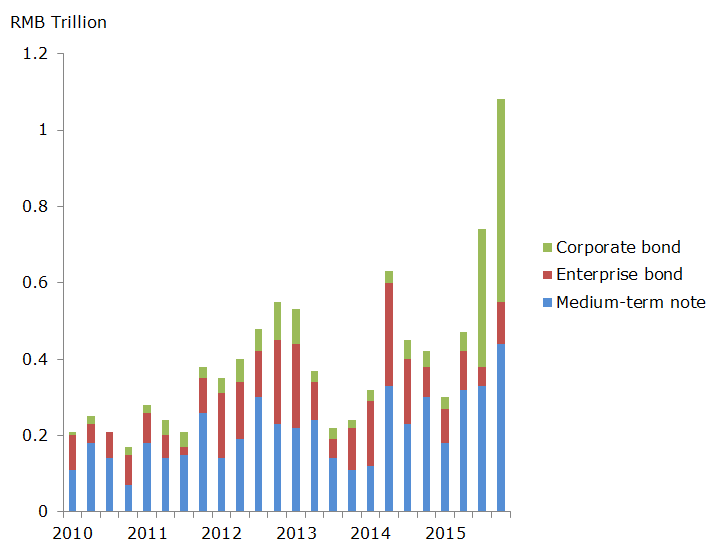

Growth: The rapid expansion of the bond market can be traced back to several factors. First, the government intends to boost the proportion of “direct financing” via bonds and equity issuances, as opposed to “intermediated” bank lending. In May 2014, the State Council issued the Guiding Principles for the Healthy Development of Capital Markets, a policy document which called for increasing the share of direct financing in the economy and easing restrictions on bond issuance. Second, corporations have turned to the bond market for raising money as funding costs there have been more attractive than bank lending. As shown in Figure 1, issuance of corporate bonds and medium-term notes has grown dramatically over the past year. Finally, government bond issuance has increased significantly as local governments have “swapped” their bank loans into bonds as part of a central government plan to restructure local debts.

Figure 1 – Corporate Bond Issuance

Source: IMF

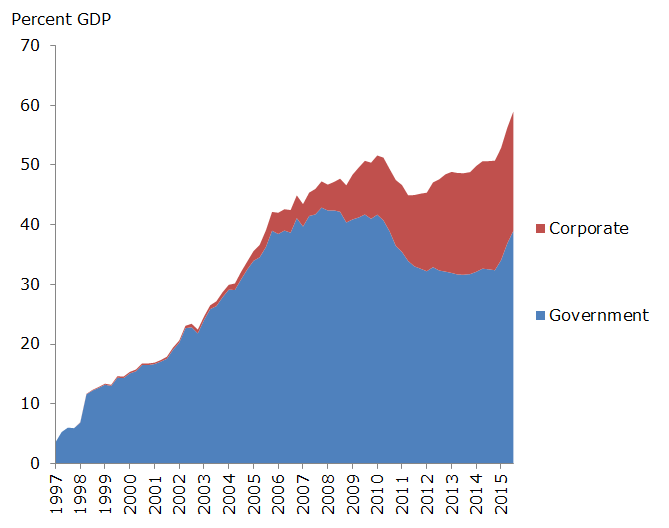

Figure 2 shows the enormous growth of the bond market over the past two decades, particularly the rapid pace over the past year. The size of the total bond market relative to GDP, however, still lags behind the levels in many other large Asian economies indicating room for continued growth.

Figure 2 – China’s Bond Market Relative to GDP (Outstanding)

Source: Asia Bond Monitor

Openness: Foreign investors, both central banks and institutional investors, have gained greater access to China’s bond markets in recent months. For foreign central banks, the changes are linked to China’s quest to have the renminbi included in the International Monetary Fund’s (IMF) Special Drawing Rights (SDR) basket. One of the requirements for SDR inclusion is that a currency be “freely usable,” meaning that the IMF, central banks and other public institutions have sufficient access to onshore markets to perform IMF-related and reserve management transactions without significant impediments.

Though China’s capital controls remain in place, over the past year, policymakers have taken steps to meet the IMF’s freely usable standard. In July 2015, foreign central banks and sovereign wealth funds were given access to the interbank market. In April 2016, the rules were updated to remove restrictions on investment size and repatriation of funds.

New policies have also reduced restrictions on investments by foreign commercial banks, insurance companies, securities companies, and investment funds. In February 2016, the PBoC announced that these entities would be allowed to invest in the interbank market, subject to some macroprudential restrictions. The same month, reforms were announced for the Qualified Foreign Institutional Investors (QFII) program, which allows foreign investors to purchase onshore bonds and equities. The initial lockup period for QFII funds was cut significantly, from one year to three months. Quotas for investors now no longer require individual approval and are instead awarded based on assets under management, subject to a cap. Finally, QFII funds will be able to redeem investments on a daily rather than weekly basis, subject to a 20 percent per month total drawdown limitation.

While these changes are positive, many foreign investors remain apprehensive of investing in the Chinese market. These concerns stem from the August 2015 equity market downturn and the government’s decision to place restrictions on the sale of shares in order to stem losses. The extent to which foreign investors take advantage of these new reforms will depend on confidence that similar restrictions will not be used on foreign investors in the future.

Risk: Corresponding with the growth and increasing openness of the bond market is an upsurge in risk. Bond defaults in China have historically been quite rare. The yield on Chinese central government debt is low, signifying market confidence in China’s creditworthiness. The debt of Chinese local governments trades at only slightly higher levels, reflecting an implicit belief that the central government will backstop local governments.

Previously, corporate bond issuances followed a similar pattern. Defaults on domestically issued bonds were non-existent and the majority of bonds were issued by large state-owned enterprises with an implicit guarantee of government support. As a result, yield spreads in the corporate bond market provided investors little information on the actual riskiness of corporate issuers.

Things began to change after Chaori, a private solar panel manufacturer, became the first company to default on a domestic bond in March 2014. Over the following two years, several more firms have defaulted, postponed payments or restructured debt, including several large state-owned enterprises. 10 companies have defaulted on bonds this year so far, with more likely to occur in the future.

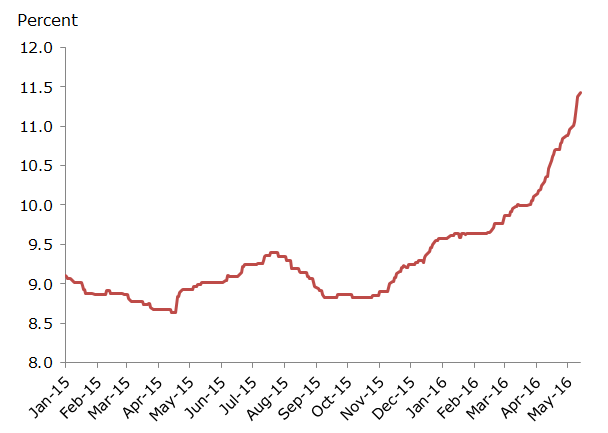

The increase in defaults has led to a negative shift in sentiment regarding the bond market. The defaults of state-owned enterprises were especially shocking to investors as government support failed to materialize or was insufficient relative to the size of the problem. Thus far this year, 70 companies have cancelled or postponed new issuances of bonds, sensing that investors are growing more skeptical. As Figure 3 shows, the change in investor perceptions has also led to a widening of the spread between higher and lower rated corporate bonds over the past year and a half. While borrowing costs for companies with highly rated debt have remained relatively low, accessing the bond market is becoming more expensive for risky borrowers.

Figure 3 – Corporate Bond AAA- and BBB Spread

Source: Bloomberg

China’s bond market now stands at a crossroads. Rapid growth has quickly transformed it into one of the largest markets in the world. The Chinese government’s commitment to opening up the bond market means that foreign investors may begin to play a much larger role. Finally, a growing number of defaults are challenging many of the previously held assumptions investors had regarding risk. If handled correctly, these trends have the potential to be positive developments. A large and open bond market that accurately prices risk would help the Chinese financial system to become less bank-dependent and more efficient. However, each of these trends also has the potential to contribute to financial volatility if reforms and regulation do not keep pace.

The views expressed here do not necessarily reflect the views of the management of the Federal Reserve Bank of San Francisco or of the Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System.