Hanjin Shipping, South Korea’s largest shipping conglomerate and the ninth largest in the world, entered receivership in August 2016 after creditors refused it a much-needed support line. Saddled with almost $6 billion in debt, the company—which employs approximately 5,000 people worldwide and operates the Long Beach Terminal near Los Angeles—is the most prominent casualty of the recent global shipping downturn, which was spurred by a drop off in global trade, the slow recovery of large advanced economies, and the slowdown of the Chinese economy after the global financial crisis.

As part of its receivership, Hanjin plans to liquidate assets to cover outstanding loans and then submit a restructuring plan by early 2017. The company’s viability seems increasingly unlikely, especially if Hanjin sells many of its most productive assets as expected. Meanwhile, the fallout from the proceedings will likely have implications far beyond the shipping industry.

Bank Exposure to Shipping Industries is Manageable

Shipping and shipbuilding play a key role in Korea’s economy, where exports account for more than 50 percent of GDP. Despite the industries’ prominent role, Korean bank exposure to them is manageable. According to Fitch Ratings, total shipping and shipbuilding-related loans account for only 2.3 percent of all loans by Korea’s big four banks, though smaller banks in shipping centers likely have higher concentrations. Moreover, while 12 percent of all shipping and shipbuilding-specific loans were non-performing at the end of June 2016, the non-performing loan ratio for the broader banking system stands at a much healthier 1.7 percent.

Policy banks have greater exposure to the shipping and shipbuilding industries, however. These banks have a mandate to lend to industries considered vital to the country’s economic development and have acted as an essential financial backstop. Loans by two policy banks, Korea Development Bank and Korea Export Import Bank, account for more than 60 percent of shipping-related loans, and amount to roughly 3.5 percent of GDP. The policy banks’ greater exposure (around 13 percent of policy banks loans are to the two industries), has driven their NPL ratios higher to 6.7 percent and 3.35 percent, respectively. Still, the Korean Government has a legal obligation to guarantee the solvency of these policy banks and has already outlined measures to recapitalize the banks to ensure that they meet minimum Basel III requirements. While capital levels and credit quality at the Korean policy banks warrant close attention amid ongoing industry restructuring, the threat to the banking system is still small due to the government’s support.

Bailing Out Shippers

On October 31 this year, Korea’s Ministry of Strategy and Finance (MOSF) announced a plan to buttress the shipping and shipbuilding industries. The government plans to spend almost $10 billion over the next three and a half years buying 250 new ships, and will create a fund to help shipping companies finance additional ships; the government has also said it will encourage shipping companies to reduce workforce and sell non-core assets to help them survive. Just a week later, as part of the receivership, Hanjin sold container shipping assets to Korea Line, a mid-sized bulk shipping company that did not have a container shipping segment prior to the purchase. In choosing Korea Line’s bid, the judge overseeing the sale cited both price and Korea Line’s intention to retain more of Hanjin’s staff as factors for its selection. In that sense, the judge’s decision mirrors the MOSF’s broader “bailout” of the twin industries even as global demand appears to warrant a cut instead. Both demonstrate the difficulty the government faces reconciling the need to cut capacity in large and nationally significant industries undergoing structural shifts.

Korea Remains Vulnerable to Global Trade Slump

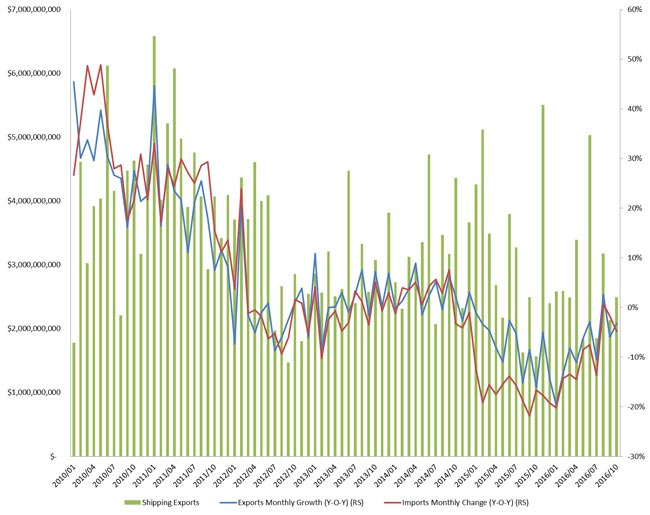

The challenges in the shipping industry highlight the trouble that a drop in global trade and lagging foreign demand pose to South Korea’s economy. Hanjin and the shipping industry are emblematic of the role that trade plays in the export-reliant Korean economy. The slowdown in China, which plays a major role in the global trade slump, is particularly difficult for Korea, which shipped 26 percent of its exports to the country in 2015. As global trade has slumped, the contribution of exports to Korean GDP has lagged. Ramifications of the strong reliance on trade have been evident for some time, as both exports and imports have fallen almost every month, year-over-year, for the better part of nearly two years (see Figure 1), after having been essentially flat from 2012 to 2014.

Other Asian economies share similar woes: three major Japanese shippers have merged a portion of their businesses, and Taiwan announced a $1.9 billion bailout for its shipping industry, all since Hanjin entered receivership. Reduced global trade means lower demand for shipping services as well as less demand for ships. In the meantime, Korea and other export-oriented Asian economies will remain vulnerable to the slowdown in global trade and the overcapacity in the shipping industry.

The views expressed here do not necessarily reflect the views of the management of the Federal Reserve Bank of San Francisco or of the Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System.