As they transform the payment systems in countries like China and India, Asia’s fintech giants are setting their sights on cross-border remittances. Will the new entrants drive down costs in a region dependent on payments sent home by overseas workers? Their initiatives add to the existing work of a number of traditional financial institutions and non-bank start-ups seeking to transform the region’s remittance market, which could help promote equitable, inclusive growth in developing Asia.

Fintech Giants Enter the Remittances Market

Over the past year, Tencent and Alibaba, two of China’s leading technology conglomerates, have entered the international remittance market by targeting Filipino workers based in Hong Kong. The Philippines is well known for its dependence on remittances, which contribute roughly 10% of economic activity. Hong Kong’s 170,000 Filipino workers represent the city’s largest ethnic minority, and together they send an estimated $770 million back home on a yearly basis. Last year, Tencent became the first Chinese fintech giant to incorporate remittance payments into its broader WePay app, with a product called “We Remit.” Notably, this service does not require a bank account; WeChat users can top up their mobile wallet at local convenience stores. Alibaba’s Alipay launched its own remittance product in June 2018. Both services rely on collaboration with local firms.

In India, meanwhile, the country’s fintech payment leader Paytm—owned in part by Ant Financial—is preparing to enter the remittances business through its Paytm Payments Bank. India is the world leader in remittance receipts, with an estimated $65 billion in 2017. U.S. fintech payments leader PayPal, which launched an Indian digital payments platform in November 2017, is also eyeing the market. PayPal is digitizing a previously cumbersome process required of firms and individuals seeking to remit payments into India from overseas in the hopes of reducing time and cost to make the company’s product more competitive. Other firms active in India’s digital payments space, which we covered earlier this year, are likely to follow suit.

In entering the remittance space, fintech firms are betting that minimizing or eliminating fees for remittances will help them gain market share. During their initial launch, both Tencent’s and Alipay’s Philippines remittance products offered their services for free. Tencent has signaled that any future remittance fees will be cheaper than those charged by existing service providers, while Alipay claims to aim for nearly zero transaction costs.

How Low Can Costs Go?

Average remittance pricing from around the world indicates that lower fees are possible, though near-zero-fee payments are likely unachievable unless firms are willing to operate at a loss, at least in the near-term. Globally, mobile phone-based remittance providers consistently offer lower costs compared to banks and traditional money transfer operators. But they still charge an average fee of 3.20% according to World Bank data for the quarter ended June 30, 2018. This may represent the existing floor new entrants will attempt to lower through innovation. Indeed, the United Nations Sustainable Development Goals have targeted the same global 3% transaction cost as achievable by 2030.

Efforts to lower remittance costs will rely on more than customer smartphone access, better software, and clever user interfaces. Alipay, for example, is aiming to use blockchain solutions to enhance the speed, reliability, and affordability of cross-border transactions. But that strategy and others must still contend with the basic realities of laws and regulations that shape how money crosses borders, including some unavoidable complexities. Take Alipay’s new Hong Kong-Philippines remittance product. The service will be offered by Alipay Payment Services (HK), a Hong Kong-incorporated entity through which the company holds a stored value license issued by the Hong Kong Monetary Authority—and that’s just on the Hong Kong end. In the Philippines, Alipay is partnering with GCash, the payment affiliate of Globe Telecomm, a Philippines telecommunications firm. As if to emphasize the cross-border challenge for start-ups, the bridge for these transactions will be Standard Chartered bank, the U.K.-based giant of emerging market banking, which has the operational capability to conduct foreign exchange and cross-border payments.

To the extent fintech firms are able to reduce the role of intermediaries and eliminate or automate front- and back-end processes in remittance transactions, this complex cross-border chain might be shortened, improving efficiency and reducing costs. As an example, PayPal’s new India remittance offering aims to reduce the time and cost of the country’s Foreign Inward Remittance Certificate documentation, which previously required receiving parties to visit a beneficiary bank to file a form and pay a fee, and then interface with another foreign correspondent bank before receiving payment. Still, there may well be a limit to how low costs can fall given the complexities of existing cross-border payment systems—not to mention foreign exchange-related risks often assumed by remittance operators.

Modest Cost Reductions Can Still Help Reduce Poverty in Asia

While achieving near-zero remittance costs is probably unrealistic in the near term, remittance transaction costs don’t need to fall close to zero to for them to have a major economic impact, particularly for Asia’s most impoverished. Examining the impact of remittances on 10 Asian countries from 1981 to 2014, Asian Development Bank econometric analysis found that the poverty gap—measured as the distance, in dollars, between the average impoverished citizen and the poverty line—declines by over 20% for every 1% increase in international remittances. Likewise, successes in reducing costs would increase net remittances and offer the same expected benefit.

Asia’s Remittance Costs Have Room for Improvement

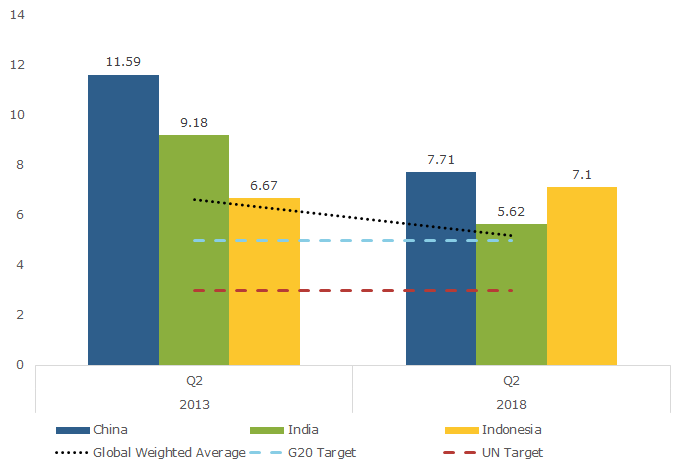

(Cost of Sending Remittance, %)

That’s good news for Asia, which has plenty of room to lower costs before getting close to zero. World Bank data shows average remittance costs in East Asia and the Pacific were 7.32% of transaction value as of June 30, 2018, with South Asia a more competitive 5.17%. Among those countries reported individually in World Bank data, China (7.71%), India (5.62%), and Indonesia (7.10%) all have ample room to reduce costs. By simply targeting reductions to levels set by multilateral organizations like the G20 (5%) or UN Sustainable Development Goals (3%), many developing Asian economies could drastically reduce remaining rates of poverty, not to mention improve the lives of the middle-class. Considered in terms of development assistance, reductions in remittance fees could generate savings equivalent to the annual foreign aid countries like India and the Philippines receive from the World Bank.

With expanding smartphone ownership across the region and continued innovation in mobile payments driven by a mix of start-ups, traditional institutions, and government policies, reducing costs down to the 3% UN target seems quite achievable. While cost reductions of a few pesos or rupees per transaction may not seem like much, over time the resulting savings could make a big difference to the region’s lower and middle classes.

The views expressed here do not necessarily reflect the views of the management of the Federal Reserve Bank of San Francisco or of the Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System.