Sylvain Leduc, executive vice president and director of research at the Federal Reserve Bank of San Francisco, shared views on the current economy and the outlook from the Economic Research Department as of October 16, 2025.

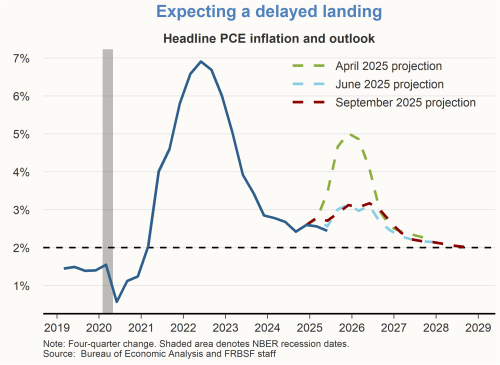

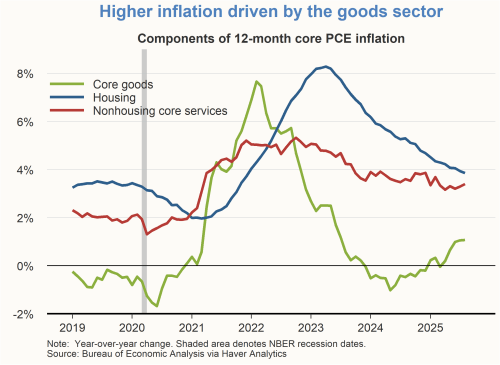

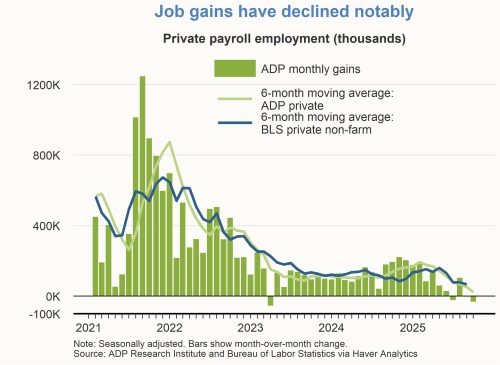

Progress on reducing inflation has been uneven of late. Inflation in the core goods sector has been rising in recent months, suggesting that some businesses are partly passing on higher tariff rates to consumers in the form of higher prices. But broader spillovers to services inflation have been limited, and market participants continue to perceive the recent rise in inflation as temporary. In the labor market, monthly job gains have declined notably this year, and, while the unemployment rate remains historically low, it has slowly climbed to its highest level since 2021. We expect the unemployment and inflation rates to rise modestly through mid–2026 and then start to decline. Due to the recent federal government shutdown, important economic data, including the September 2025 employment report, have not been released. This development adds further uncertainty to an already uncertain environment.

Several factors have mitigated tariff impacts

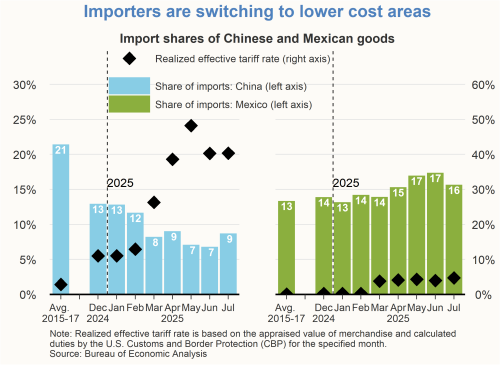

Data suggest that U.S. importers have been proactive in switching to lower-cost producers in a relatively short amount of time. The share of imported goods from China has declined by about 4 percentage points since the start of the year, partly reflecting the anticipation of higher tariff rates that were announced starting in April 2025. In contrast, the share of imported goods from Mexico has increased, likely due to the tariff-exempt status of most Mexican products and the much smaller tariff rates imposed on the remaining Mexican goods versus Chinese goods.

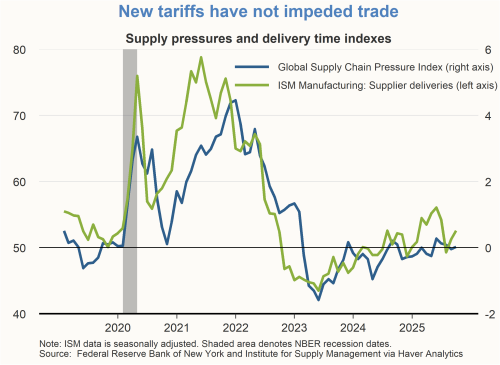

Moreover, the New York Fed’s Global Supply Chain Pressure Index suggests that higher tariff rates have not led to significant disruptions in global supply chains as was feared in April. Similarly, the Institute of Supply Management’s Supplier Delivery Index suggests that delivery times have remained fairly stable this year.

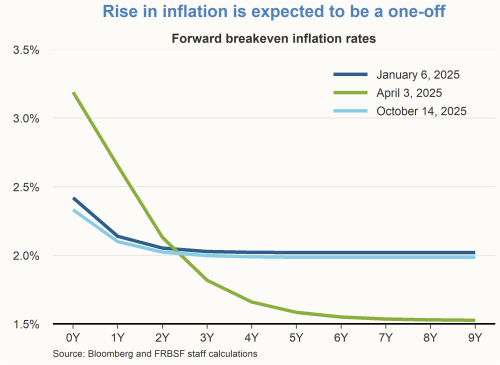

The breakeven inflation rate, a measure of market-expected inflation computed from the difference between nominal Treasury yields and yields on Treasury Inflation Protected Securities (TIPS), indicates that market participants continue to view the recent rise in inflation as temporary, helping to mute inflationary pressures. Specifically, market participants expect elevated inflation this year to gradually decline towards 2%. The recent market-expected inflation path is now close to the path observed at the start of the year.

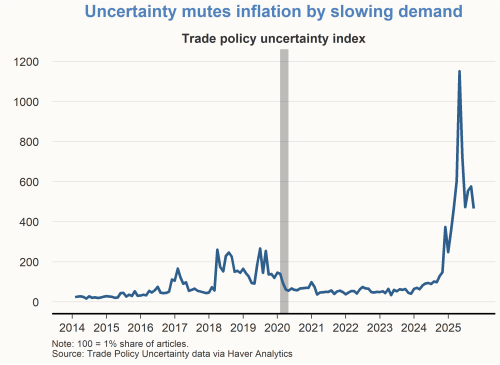

The U.S. trade policy uncertainty index has declined notably from the peak reached in April 2025 when new tariffs were announced, but the index remains materially above 2024 levels. Elevated uncertainty acts as a negative demand shock, putting downward pressure on inflation and economic activity. Hence, the tariff-related increase in uncertainty in 2025 has likely moderated inflationary pressures, while contributing to a weaker labor market.

Little signs of goods inflation spilling over to services inflation

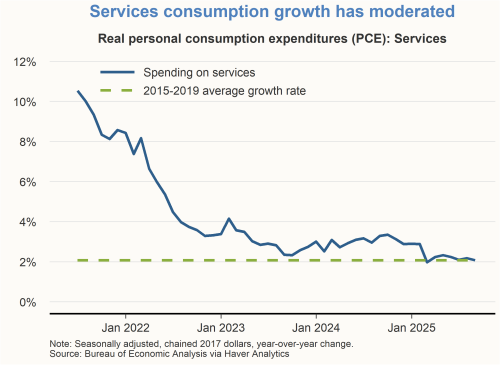

The rise in goods inflation from the new tariffs has so far not spilled over to services inflation, in contrast to what happened when inflation surged in 2021 and 2022. A possible explanation is that, in contrast to the post-pandemic period, the growth rate of services consumption has slowed substantially and is now in line with the average growth rate from 2015 to 2019.

The weaker labor market has also helped mitigate inflationary pressures. Due to the recent federal government shutdown, the Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS) has not released its monthly employment report for September 2025. Private-sector job data recorded by the firm, Automatic Data Processing (ADP), a large payroll software provider, offers an alternative reading on the status of the labor market. The six-month moving average of ADP job gains tracks closely with the six-month moving average from the BLS. The ADP data for September indicates a loss of 32,000 private-sector jobs, suggesting a continued weakening of the labor market.

How has the growth of artificial intelligence impacted the labor market?

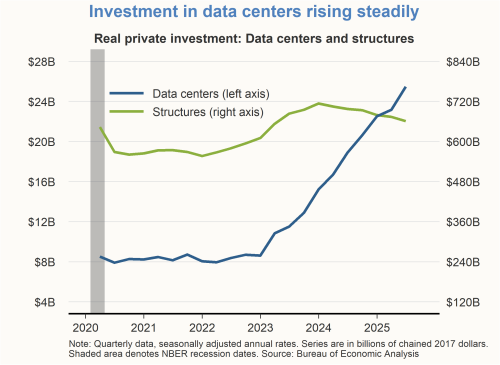

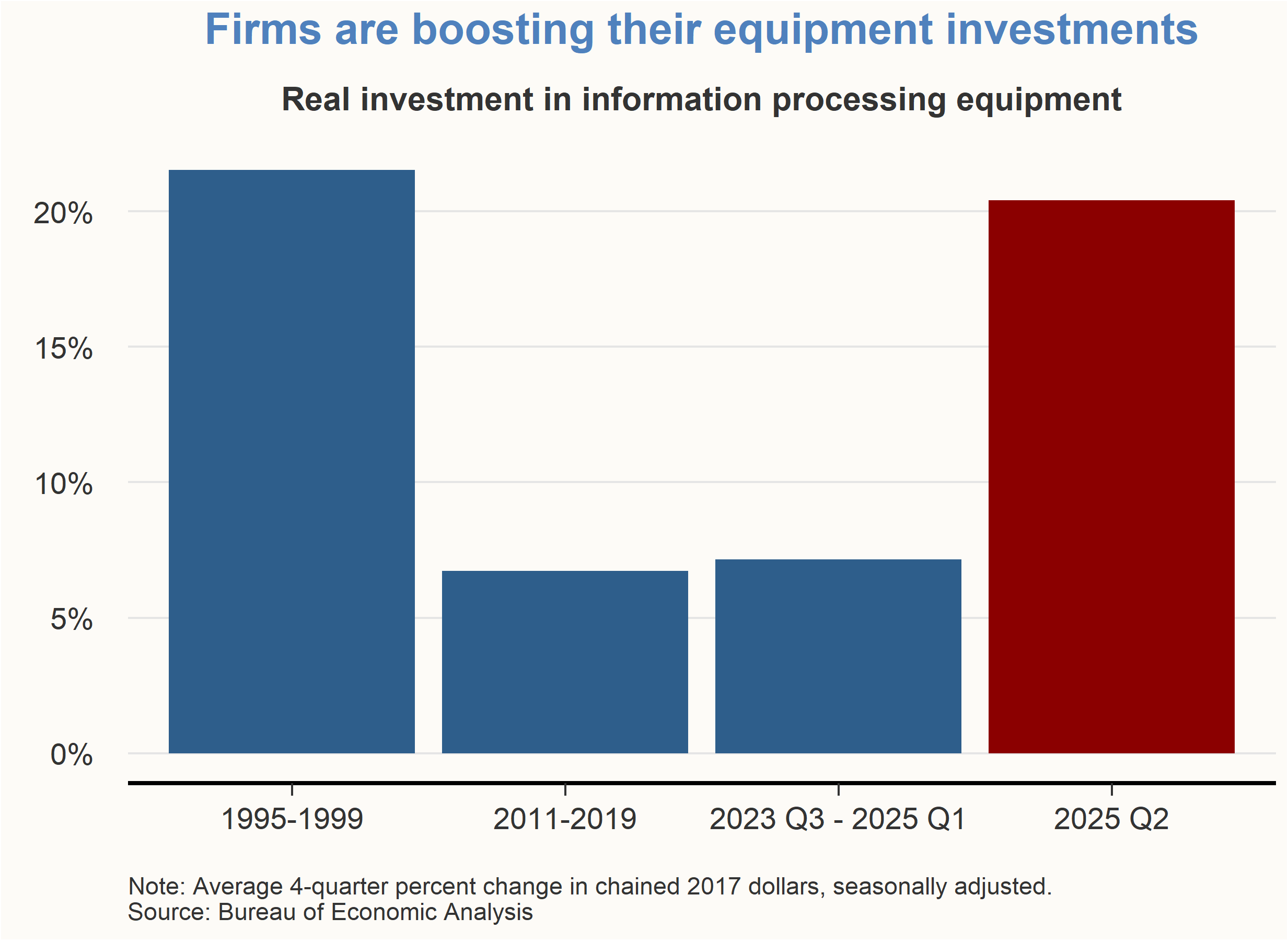

Businesses have been investing in data centers to help power the fast-rising use of artificial intelligence (AI) technologies. In contrast to the stagnant growth of investment in structures in general, investment in data centers has been growing rapidly in recent years, albeit from low starting levels. Moreover, investment in information processing equipment jumped in the second quarter of 2025, showing a growth rate similar to that observed during the tech boom of the mid- to late 1990s.

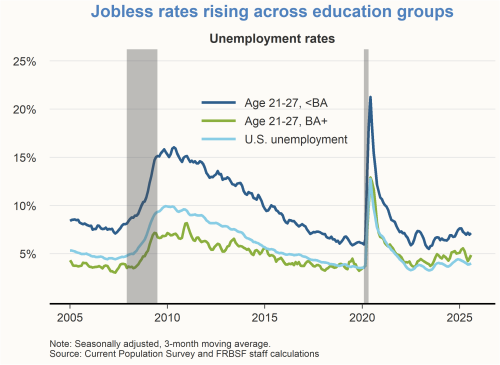

These investments could in principle impact the labor market to the extent that firms’ adoption of AI technologies serves as a substitute or complement for workers. One class of workers that may be at higher risk of displacement from firm investment in AI technologies is recent college graduates, as the rapidly evolving technology may be particularly well suited to perform entry-level office tasks. But while the unemployment rate for recent college graduates has been rising of late, the same is true for non-college graduates. It is unusual for recent college graduates to face a higher unemployment rate than we see in the aggregate economy, as has been the case for the past two years. While only suggestive, this narrow gap points to other factors impacting the status of the labor market as well, including higher tariff rates, reduced immigration, and restrictive monetary policy.

Market participants expect lower short-term interest rates

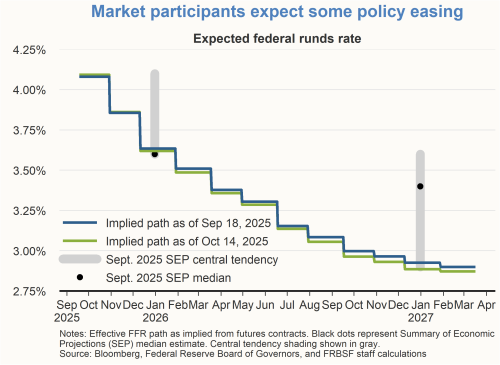

With the recent uptick in inflation readings perceived as temporary by market participants and growing evidence that the labor market has weakened of late, markets are now pricing in two more 25-basis-points cuts in the federal funds rate this year and about three additional 25-basis point cuts in 2026. These forecasts are broadly similar to the rate path contained in the Federal Open Market Committee’s Summary of Economic Projections for September.

Charts were produced by Addie New-Schmidt and Aleisha Sawyer.

The views expressed are those of the author with input from the Federal Reserve Bank of San Francisco forecasting staff. They are not intended to represent the views of others within the Bank or the Federal Reserve System. This publication is edited by Kevin J. Lansing, Karen Barnes, and Hamza Abdelrahman. SF FedViews appears eight times a year. Please send editorial comments to Research Library.