Involuntary part-time employment—the share of people who work less than 35 hours per week but want and are available to work full-time—has increased since 2023. While this contrasts with steady declines during previous cyclical expansions, it is consistent with the recent rise in unemployment. Examining worker transitions shows that fewer workers have found full-time work and a growing number have remained stuck in part-time employment. Though levels are only slightly elevated since 2023, this pattern may hint at emerging cyclical weakness in the labor market.

Economists often look beyond headline unemployment to measure the health of the U.S. labor market. One such measure is involuntary part-time employment—the number of individuals working reduced hours despite preferring and being able to work full time. Involuntary part-time employment is typically countercyclical, rising quickly at the onset of recessions and then falling gradually during recoveries. A large share of involuntary part-time workers can signal that the economy is not achieving its full labor potential.

This Economic Letter examines how involuntary part-time employment broke from its historical patterns during and after the COVID-19 pandemic. First, involuntary part-time employment during the pandemic recession rose entirely due to reduced hours for already employed workers, not because unemployed people could only find part-time work. Second, the decline in part-time employment during the initial recovery from late 2020 to late 2023 was much faster than in previous recoveries.

This behavior was broadly consistent with other measures of labor market slack, such as the job-finding rate. Specifically, the labor market during the pandemic recession was likely not as weak as implied by the historically high unemployment rate alone (Kudlyak 2025). The run-up in unemployment was associated with government-mandated shutdowns caused by the pandemic rather than a typical recessionary slowdown in demand (Kudlyak and Wolcott 2024).

Finally, we find that involuntary part-time employment has been increasing since 2023. This contrasts with earlier business cycles, when it gradually decreased throughout the entire recovery until the onset of the next recession. However, the current increase is consistent with unemployment rising modestly and other measures of labor market slack weakening over the past two years (Avaradi et al. 2025). Our microdata analysis shows that worker transition rates into involuntary part-time employment from other employment are somewhat up, while transition rates out of involuntary part-time employment are down. Our analysis also shows that during the last year, the transition rate from unemployment to involuntary part-time work declined, and workers who end up in part-time work are more likely to remain stuck there. Though the levels are only slightly elevated, these patterns hint at labor market weakening.

Involuntary part-time employment and unemployment

We use monthly microdata from the Current Population Survey (CPS) to calculate the share of involuntary part-time workers from January 1994 through August 2025. The CPS classifies each individual into one of five labor force statuses: employed full time; employed part time for economic reasons, which we refer to as involuntary part-time employment; employed part time for noneconomic reasons, which we refer to as voluntary part-time employment; unemployed; and out of the labor force. Individuals who work less than 35 hours per week are considered part-time workers.

Our focus is on individuals who work part time but desire full-time work, as opposed to those who choose to work part time for noneconomic reasons, such as family commitments. These involuntary part-time workers represent underutilized labor market resources in the economy (Canon et al. 2014, Fallick 2025, and Valletta, Bengali, and van der List 2020). The Bureau of Labor Statistics includes these workers and individuals who would like to work but are not actively searching in a labor underutilization measure known as the U-6 rate, which is the broadest official alternative to the standard U-3 unemployment rate.

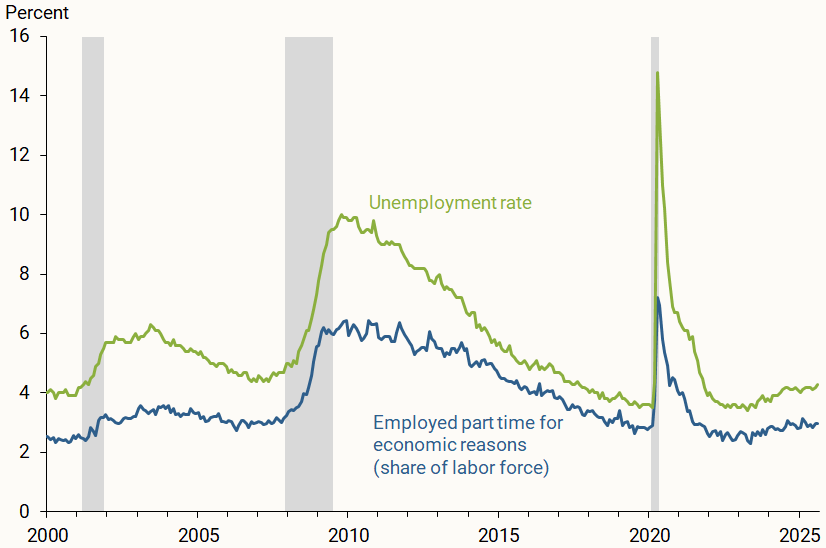

Figure 1 shows involuntary part-time employment as a share of the civilian labor force (blue line) as well as the overall unemployment rate (green line). Both series are countercyclical, increasing during recessions and declining during recoveries.

Figure 1

Involuntary part-time employment and unemployment

During the pandemic recovery, involuntary part-time work declined much faster than in previous recoveries. It fell below its pre-pandemic low within two years, ultimately reaching its lowest level in two decades. This contrasts with the recovery following the 2007-09 recession, when involuntary part-time employment remained elevated for an extended period (Valletta, Bengali, and van der List 2020).

Since 2023, involuntary part-time employment has increased from 2.5 to 2.9% of the labor force. During the same period the unemployment rate increased from 3.5 to 4.3%. To understand how involuntary part-time work behaved relative to the unemployment rate before and after the pandemic, we estimate a simple linear regression of involuntary part-time employment on the unemployment rate, using seasonally adjusted monthly data from January 1994 to February 2020. We then compare the predicted values from the regression to the actual series. We find that the predicted series closely matches the actual involuntary part-time employment series during the post-pandemic period, indicating that recent changes in the series follow typical historical patterns.

Slack business conditions or inability to find full-time work?

While overall behavior generally aligns with past experience, we use microdata to see if underlying behaviors have changed, possibly suggesting more concerns about the labor market.

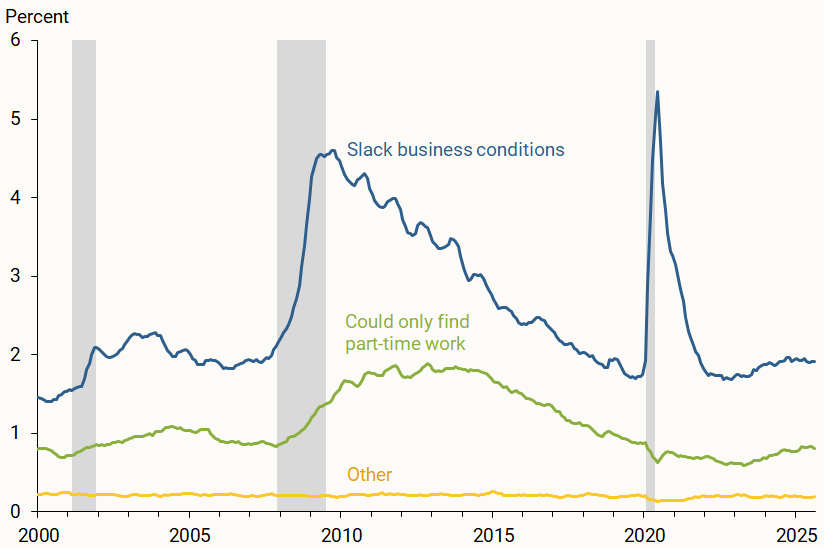

CPS data identify two main ways that workers can end up in involuntary part-time employment. The first is workers whose weekly hours were cut from full time to part time when labor demand was weak, also called slack business conditions. The second is workers who are only able to find part-time work. Figure 2 plots these groups of workers as shares of the labor force.

Figure 2

Reasons for involuntary part-time work, labor force share

Involuntary part-time employment due to slack business conditions (blue line) typically increases steeply during recessions and starts declining immediately once a recovery begins. Involuntary part-time employment due to only being able to find part-time work (green line) typically increases more gradually during recessions and continues to increase for some time into recoveries before eventually falling back slowly to pre-recession levels.

The COVID-19 recession and subsequent recovery broke from these historical patterns, and the increase and decrease in part-time employment were equally fast. The rapid spread of the pandemic prompted government-mandated shutdowns and stay-at-home orders, resulting in many workers being temporarily laid off while others saw their hours reduced from full time to part time. When restrictions were lifted, the effect on the labor market was far more immediate than the slow and uncertain recoveries from the Great Recession or the 2001 recession. The end of pandemic-related economic shutdowns, along with a series of fiscal stimulus bills, dramatically increased consumer demand and enabled a rapid return to full-time work across the economy.

Our two involuntary part-time employment categories reached their historical lows at the beginning of 2023. Since then, both categories have been increasing, though the rate due to reduced hours has flattened in recent months. While these measures of underemployment are still low by historical standards, their increase could signal underlying weakness in the labor market.

Why is involuntary part-time employment on the rise?

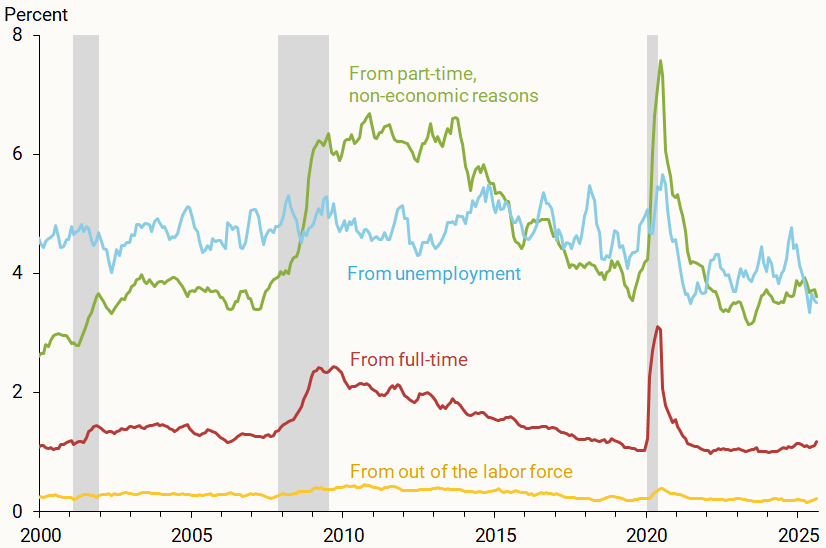

To understand why involuntary part-time employment has increased over the past two years, we examine how workers transition to and from involuntary part-time employment and other labor market statuses: full-time employment, voluntary part-time employment, unemployment, and out of the labor force. We construct the monthly transition rates by tracking individual records in the CPS from one month to the next.

Figure 3 shows the transition rates into involuntary part-time work from the other four labor market statuses. The transition rates into involuntary part-time work from full-time work (red line) and from voluntary part-time work (green line) both hit record highs in the COVID-19 recession and recovered quickly to pre-pandemic levels. Over the past two years, both series have increased from their recent low points. The transition rates from full-time work or from voluntary part-time work into involuntary part-time work have both increased. The increases suggest that a growing number of workers wanted to work full time but could not—either their full-time job was converted to part time or they could not find full-time work.

Figure 3

Transition rates into involuntary part-time work

Another development is the decrease in the transition rate from unemployment to involuntary part-time work (light blue line) from 4.8% in October 2024 to 3.5% as of August 2025. Detailed transition rates out of unemployment reveal an increase in transition rates from unemployment to full-time work or to working part time for noneconomic reasons. Thus, the decline in the rate of people moving from unemployment to involuntary part-time work has not been accompanied by declining transitions to other employment. Rather involuntary part-time work is being used less as a job destination from non-employment.

Figure 4 shows the transition rate from involuntary part-time employment to other labor market statuses as well as the rate of remaining in involuntary part-time employment over time (dark blue line). The rate of remaining in involuntary part-time employment has risen over the past few years, from 30.9% in August 2022 to 38.7% in August 2025. Additionally, these workers are having a more difficult time finding full-time work, as seen by the decline in the red line from 34.1% in January 2023 to 28.9% in August 2025.

Figure 4

Transition rates out of involuntary part-time work

Together, the developments captured by the transition rates to and from involuntary part-time work signal some weakening in the labor market over the past two years. Increasing numbers of part-time workers are finding themselves stuck in part-time employment. Though current levels of involuntary part-time work are relatively low, these developments are consistent with the rising unemployment rate over the same period, with both suggesting that labor market slack is increasing.

Conclusion

This Letter investigates the patterns of involuntary part-time employment over time and deviations from these patterns in the most recent recession and recovery.

The last two years have seen increasing levels of involuntary part-time employment, which contrasts with steady declines in previous recoveries. Worker transition rates between involuntary part-time employment and other labor force statuses show that fewer involuntary part-time workers were able to find full-time work and a growing number remained stuck in their current state. Though levels remain only slightly elevated, this pattern may hint at emerging cyclical weakness in the labor market.

References

Avaradi, Greeshma, Marianna Kudlyak, Brandon Miskanic, and David Wiczer. 2025. “Assessing the Recent Rise in Unemployment.” FRBSF Economic Letter 2025-09 (April 14).

Canon, Maria E., Marianna Kudlyak, Guannan Luo, and Marisa Reed. 2014. “Flows To and From ‘Working Part-Time for Economic Reasons’ and the Labor Market Aggregates in the Aftermath of the 2007–09 Recession.” FRB Richmond Economic Quarterly, Second Quarter.

Fallick, Bruce. 2025. “Part-Time for Economic Reasons During the Global Financial Crisis.” Federal Reserve Bank of Cleveland Working Paper 25-20.

Kudlyak, Marianna. 2025. “Unemployment and Inflation Dynamics in the Monetary Policy Armamentarium.” Chapter 16 in Getting Global Monetary Policy on Track, Hoover Institution Monetary Policy Conference Volume, edited by Michael D. Bordo, John H. Cochrane, John B. Taylor. Stanford, CA: Hoover Institution Press.

Kudlyak, Marianna, and Erin Wolcott. 2024. “Pandemic Layoffs and the Role of Stay-at-Home Orders.” Economics Letters 242(111894, September).

Valletta, Robert G., Leila Bengali, and Catherine van der List. 2020. “Cyclical and Market Determinants of Involuntary Part-Time Employment.” Journal of Labor Economics 38(1), pp. 67–93.

Opinions expressed in FRBSF Economic Letter do not necessarily reflect the views of the management of the Federal Reserve Bank of San Francisco or of the Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System. This publication is edited by Anita Todd and Karen Barnes. Permission to reprint portions of articles or whole articles must be obtained in writing. Please send editorial comments and requests for reprint permission to research.library@sf.frb.org