Download PDF (pdf, 1.0 mb)

Introduction

In recent years, numerous businesses have made headlines for refusing to accept cash as a form of payment. These businesses span a variety of industries, including airlines, eateries, sports stadiums, and general merchandise stores. This phenomenon is not just limited to a few cities, either. Cashless businesses have popped up across the country, including places like New York, Atlanta, and Chicago (Figure 1).

Figure 1

Sample of Cashless Businesses across the United States

This paper explores the impacts of businesses going cashless from various angles: the incentives and benefits for the retailer, the cost to consumers, the potential impact on cash use, and the legal implications and current laws around the subject.

Controlling Operational Costs Makes it Attractive for Businesses to Go Cashless

Much has been written already about why a business may consider going cashless, and most of these incentives are driven by cost and time savings.

Cashless businesses no longer have cash handling costs

Small- and medium-sized businesses are reported to pay tens of billions of dollars annually on cash handling expenses.1 Eliminating cash payments eliminates the costs associated with handling and transporting cash. Cashless businesses no longer need to pay banks fees to deposit and process cash and coin, nor do they need to pay for armored carriers to transport money to and from the bank.2 Additionally, these businesses no longer need to pay for employees to count and manage register balances throughout the day, enabling employees to spend more time helping customers instead. Given the fixed costs associated with accepting cash, it may be simpler and even more cost-effective for some businesses to not accept cash at all.

There are fewer opportunities for theft

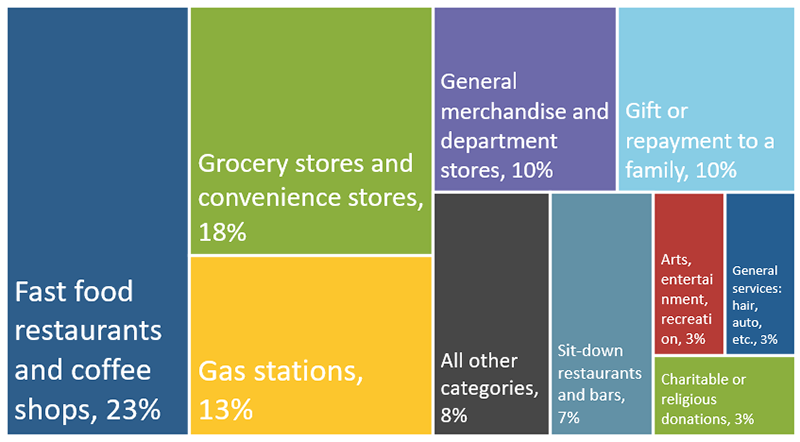

Not having cash on store premises also reduces opportunities for both internal and external robberies. Internally, businesses face a constant battle with employee theft, or “shrinkage.” The 2015 Retail Fraud Survey estimates that U.S. retailers lose $60 billion per year to shrinkage,3 though cash is just a portion of this loss, and the National Retail Federation’s 2018 Security Survey estimates the average dollar loss per dishonest employee to be $1,203.4 Externally, cash-intensive businesses can be targets for robberies. Nearly a quarter of U.S. robberies (26 percent) took place at some type of retailer—either a gas station, convenience store, or other commercial residence (Figure 2).5 When businesses forego cash on their premises, there may be fewer opportunities and incentives for internal and external theft.

Figure 2

2017 U.S. Robbery Locations

Transactions are faster

Counting cash can take time, both for the customer and the employee. Several businesses that have gone cashless have cited benefits like faster transactions and increased store throughput. Atlanta’s Mercedes-Benz Stadium found that its transition to exclusively card and mobile payment transactions not only reduced end-of-day reconciliation time but also resulted in quicker transaction times and lower wait times for customers.6 Salad chains Tender Greens and Sweetgreen found similar benefits from going cashless: Tender Greens estimates that cash transactions are four to five seconds slower than card transactions,7 and Sweetgreen found that its cashless locations processed 5 to 15 percent more transactions per hour.8 Particularly in high-volume businesses, these faster transaction times can translate to increased customer satisfaction, fewer opportunities for error in making change, and increased revenue.

By going cashless, businesses can decrease costs, reduce opportunities for theft, and offer customers a faster, more streamlined transaction experience.

Cashless Savings Come at the Cost of Financial Exclusion

While market forces and cost savings make it attractive to forego cash, the reasons not to go cashless fall under different categories of financial inclusion and consumer choice.

Some consumers are denied goods and services

Perhaps the strongest argument against going cashless is that the practice denies access to goods and services for a segment of consumers. While popular perception may be that no one uses cash anymore, nearly 6.5 percent of U.S. households were unbanked and did not have access to financial services in 2017. In other words, 6.5 percent of the U.S. population, or 8.4 million households, did not have a bank-issued debit or credit card.9 Adding in ‘underbanked’ households—households that have a bank account but use other financial services like money orders, payday loans, and check cashing—these numbers increase to 24.2 million households and nearly 19 percent of the U.S. population.9 These consumers rely heavily on cash to pay for their purchases. The 2019 Findings from the Diary of Consumer Payment Choice found that more than half (56 percent) of unbanked consumers’ transactions are made with cash.10

Even if cash-using consumers had the option to use prepaid cards to shop at cashless businesses, the switch is costly. Economist Oz Shy of the Federal Reserve Bank of Atlanta estimated the cost of this switch in a 2019 working paper that quantified the economic burden of cashless stores on consumers who do not own credit or non-prepaid debit cards. Shy found that only when the cost of using cash is two or more times greater than the cost of using a card is the consumer indifferent; at a lower cost differential, the consumer reports a loss of economic utility.11

Other consumers may trust or only have access to cash

Some Americans willingly choose to exclude themselves from the banking sector and value anonymity at the point of sale. In its 2017 National Survey of Unbanked and Underbanked Households, the FDIC found that one third of unbanked households don’t trust banks, and other participants avoided banks because of privacy concerns or unpredictable bank fees.12

Furthermore, other consumers may be using cash because they may momentarily only have access to cash. Non-cash payments, like cards and electronic payments, rely on the availability of card networks. Network disruptions, concerns about data integrity, and natural disasters can all render non-cash payments unavailable or unreliable.

Whether consumers are willingly using cash (out of privacy or distrust) or unwillingly using cash (due to network outages or lack of access to their accounts), cashless businesses deny these customers the opportunity to participate in a certain segment of the economy.

Businesses become vulnerable to card companies’ fees

While going cashless generally translates to cost savings for retailers, these retailers could also be dropping their cheapest form of payment. The Bank of Canada conducted a study of 500 businesses in 2008 and found that, for these retailers, cash was cheaper to accept than credit and debit cards. The study found cash to be cheaper than credit cards even at the lowest quartile credit card rate of 1.75 percent, and cash to be cheaper than debit cards for all transactions below $12.60 where merchants paid debit card fees as low as 7 cents.13 A more recent 2011 study by economist Layne-Farrar estimates the transaction costs associated with cash, check, and debit for five types of retailers, including quick serve retailers, big box discount stores, supermarkets, gas stations, and travel retail stores. The study found that even when including costs like point-of-sale transaction time, back office costs, counterfeit costs, and fraud prevention, cash was cheaper than debit in terms of cost per $100 of sales. Cash cost retailers $0.53 per $100 of sales, compared to $1.12 for signature debit and $0.81 for PIN debit. Her study did not include credit cards.

In addition to narrowing down their tender types to potentially more expensive forms of payment, cashless businesses also increase their vulnerability to card companies’ fees. When retailers swipe a customer’s credit card for payment, card companies charge them a ‘card-swipe’ or interchange fee for each debit and credit transaction. This fee is usually around one to two percent of the transaction total, and these interchange fees alone earned Visa and MasterCard a combined $43 billion in 2018.14 When businesses shift from cash or a blend of payment alternatives to card-only, they have little recourse when card companies raise fees, especially in a relatively concentrated card market. Regardless of where the ultimate incidence of these costs falls, the costs necessarily will be borne by either the retailer, in the form of lower margins, or by the consumer, in the form of higher costs.

The Rise of Cashless Businesses and their Impact on Cash

If the current trend of cashless businesses continues to gain momentum, the impact on consumer cash could be significant, particularly if the shift occurs in certain key industries.

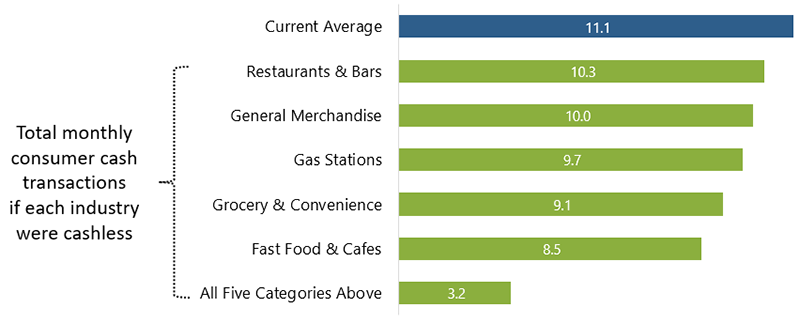

The Federal Reserve’s 2019 Findings from the Diary of Consumer Payment Choice, an annual study tracking a nationally representative group of U.S. consumers and their transactions over a three-day period, found that cash transactions were primarily driven by a few key categories (Figure 3). Nearly a quarter of cash transactions (23 percent) in 2018 were used for fast food-type purchases, such as coffee and grab-and-go meals. Grocery and convenience store purchases were the second leading driver of cash transactions, making up 18 percent of cash purchases, followed by gas (13 percent), general merchandise (10 percent), person-to-person (P2P) payments (10 percent), and sit-down restaurants (7 percent).

Figure 3

Categories of Cash Transactions

While there is no comprehensive registry of cashless businesses and their industries, many of the retailers making headlines fall under these same cash-intensive categories: fast food, restaurants, and general merchandise stores. The table in Figure 4A estimates the worst-case cash scenario if all businesses in these categories were to forego cash. For the categories mentioned earlier where there has been a rise in cashless businesses (fast food, grocery, general merchandise, restaurants), the table uses Diary data to calculate three columns:

- The average number of “in-person” brick-and-mortar payments made per consumer per month in this category,

- The average number of cash payments made per consumer per month in this category, and

- The category’s share of total cash payments. The Diary found the average consumer makes 11 cash transactions per month. This column takes column B (average number of cash payments made for this category) and divides it by 11.

Figure 4A

Average Number of Cash Payments per Person per Month

| Category | (A) Brick & Mortar Payments |

(B) Cash Payments |

(C) Category’s Share of Total Cash Payments |

|---|---|---|---|

| Fast Food & Cafes | 6.0 | 2.6 | 24% |

| Grocery & Convenience stores | 6.9 | 2.0 | 18% |

| Gas Stations | 4.1 | 1.4 | 13% |

| General Merchandise stores | 4.9 | 1.1 | 10% |

| Restaurants & Bars | 2.5 | 0.8 | 7% |

| Total per Month | 31 | 11 | 100% |

Figure 4B visualizes the data in table 4A. It shows that depending on the category and current amount of cash use within that category, a rise in cashless businesses can have a significant impact on cash use. If all businesses in the “Fast Food & Cafes” category went cashless, consumers would make 2.6 fewer cash transactions a month (out of the monthly average of 11 total cash transactions). This shift translates to a 24 percent reduction in monthly cash transactions. Similarly, if all “Grocery & Convenience stores” went cashless, there would be an 18 percent decline in cash transactions.

If we extrapolate this and suppose all businesses in the “Fast Food & Cafes,” “Grocery & Convenience,” “Gas Stations,” “General Merchandise,” and “Restaurants & Bars” categories (all five categories listed in Figure 4A) go cashless, monthly cash transactions would drop by 72 percent, decreasing from 11 to 3 cash transactions per consumer per month. In short, wide adoption of cashless practices can have a substantial impact on cash use.

Figure 4B

Average Number of Cash Payments per Person per Month

The Current Legal Landscape on Cashless Businesses

From a legal perspective, no federal statute currently mandates that businesses must accept cash. The closest relevant statute is the Federal Reserve’s “Legal tender” statute, Section 31 U.S.C. 5103, stating, “United States coins and currency [including Federal Reserve notes and circulating notes of Federal Reserve banks and national banks] are legal tender for all debts, public charges, taxes, and dues.” In other words, while cash is a valid way to pay for debts, it is not required to be accepted for goods and services. Private businesses are free to decide for themselves whether or not to accept cash, unless their state or local law says otherwise.15

In that spirit, two state governments have passed legislation banning cashless businesses. Massachusetts was the first state to have an official stance, with its 1978 “Discrimination Against Cash Buyers Amendment” requiring that the state’s merchants accept cash.16 New Jersey recently became the second state to ban cashless businesses, signing a bill in March requiring its stores and restaurants to accept cash at brick-and-mortar locations.17

Cities are beginning to take action as well. In February of 2019, Philadelphia passed legislation prohibiting cashless stores starting in July of 2019.18 San Francisco soon followed suit, passing an ordinance requiring brick-and-mortar businesses to accept payment in cash for goods and services in May of 2019.19 San Francisco’s legislation states, “The purpose of this [law] is to ensure that all City residents—including those who lack access to other forms of payment—are able to participate in the City’s economic life by paying cash for goods and many services.”20 Additional cities, including New York City, are considering similar legislation.21

Conclusion

The topic of cashless businesses is a complex and nuanced issue. On one hand, it can make economic sense for a business to go cashless. Transactions are faster, opportunities for theft are reduced, businesses may be less attractive robbery targets, and stores can eliminate cash handling costs. On the other hand, the move away from cash can symbolize, even inadvertently, support for financial exclusion of certain consumers. This trade-off raises a few philosophical questions: Do consumers have a right to use cash? Who bears responsibility for financial inclusion?

While the legal landscape remains mixed, some retailers are backing off their cashless plans. In 2018, in response to strong customer feedback, burger chain Shake Shack decided not to go fully cashless in their restaurants;22 AmazonGo announced plans in March to enable customers to pay with cash;23 and famously cashless salad chain Sweetgreen announced in April of 2019 that all of its locations will accept cash again after experimenting with going cashless for more than two years.24

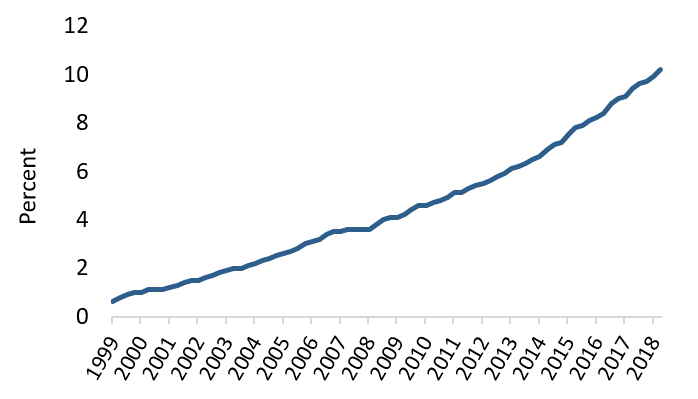

Even if the legal tide turns against cashless businesses, other emerging retail trends pose similar risks to financial inclusion and to cash. One increasingly popular brick-and-mortar trend is the “showroom model,” where customers can physically try on and interact with products but ultimately purchase them online.25 Another retail trend is the $57 billion “on-demand economy,” where consumers can order goods, meals, and services instantaneously through their smartphones.26 While these innovations can offer tremendous benefits to both retailers and consumers, they pose similar questions around financial exclusion. Both require consumers to pay with some type of electronic or card payment, and both deny consumers the opportunity to use cash. Still, e-commerce’s share of total retail sales reached 10 percent in 2019, with no signs of slowing down or stopping (Figure 5).

Figure 5

E-Commerce’s Share of Total Retail Sales

The Cash Product Office will continue to monitor the legal landscape around cashless businesses and, more generally, trends and changes in the retail space to understand their impact on consumer payment behavior and cash use.

Acknowledgements

This paper would not have been possible without the support and contributions of the following individuals: Alexander Bau, Jonathan Bromma, Amy Burr, Ben Gold, Natallia Koller, Kelly McGuire, Shaun O’Brien, and Margaret Riley.

About the Cash Product Office

As the nation’s central bank, the Federal Reserve ensures that cash is available when and where it is needed, including in times of crisis and business disruption, by providing FedCash® Services to depository institutions and, through them, to the general public. In fulfilling this role, the Fed’s primary responsibility is to maintain public confidence in the integrity and availability of U.S. currency.

The Federal Reserve System’s Cash Product Office (CPO) provides strategic leadership for this key function by formulating and implementing service level policies, operational guidance, and technology strategies for U.S. currency and coin services provided by Federal Reserve Banks nationally and internationally. In addition to guiding policies and procedures, the CPO establishes budget guidance for FedCash® Services, provides support for Federal Reserve currency and coin inventory management, and supports business continuity planning at the supply chain level. It also conducts market research and works directly with financial institutions and retailers to analyze trends in cash usage.

Footnotes

1. Southern California Public Radio. Why more and more LA businesses are refusing your cash. April 2018.

2. Vox. Why cashless retailers put low-income people at even more of a disadvantage. November 2018.

3. Forbes. New report identifies U.S. retailers lose $60 billion a year, employee theft top concern. October 2015.

4. National Retail Federation. National Retail Security Survey. 2018.

5. Federal Bureau of Investigation. 2017 Crime in the United States.

6. Mercedes Benz Stadium Payments FAQ.

7. SCPR. Why more and more LA businesses are refusing your cash. April 2018.

8. New York Times. Where a suitcase full of cash won’t buy you lunch. July 2016.

9. Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation. 2017 FDIC National Survey of Unbanked and Underbanked Households.

10. O’Brien, Shaun and Raynil Kumar. 2019 Findings from the Diary of Consumer Payment Choice.

11. Shy, Oz. Cashless Stores and Cash Users. Federal Reserve Bank of Atlanta. Working Paper 2019-11. May 2019.

12. Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation. 2017 FDIC National Survey of Unbanked and Underbanked Households.

13. Arango, Carlos and Varya Taylor. Bank of Canada. Merchants’ Costs of Accepting Means of Payment: Is Cash the Least Costly?. January 2008.

14. Wall Street Journal. Visa, MasterCard near settlement over card swipe fees. June 2018.

15. Federal Reserve System. Currency FAQs.

16. Boston Magazine. Should Boston Stop Using Cash? February 2016.

17. Politico. Murphy signs bill banning most cashless stores in New Jersey. March 2019.

18. New York Times. Philadelphia bans ‘cashless’ stores amid growing backlash. March 2019.

19. City and County of San Francisco. Board of Supervisors. Ordinance 190164.

20. SF Examiner. SF approves ban on cashless stores. May 2019.

21. CNN. Retailers want to go cashless. But opponents say that’s discriminatory. March 2019.

22. Eater. Shake Shack’s Grand Cashless Experiment Has Failed. May 2018.

23. TechCrunch. Cashierless AmazonGo stores are planning to accept cash. April 2019.

24. Bloomberg. Sweetgreen will once again accept cash. April 2019.

25. New York Times. Retailers experiment with a new philosophy: smaller is better. November 2017.

26. Inc. $57 Billion Dollar Opportunity: the State of the On Demand Economy in 2017.