The American Recovery and Reinvestment Act of 2009 (ARRA) was signed into law on February 17, and already its impact is being felt in state capitals around the nation. Governors and state legislators are incorporating expected stimulus funds into 2009-2010 budgets and a number of state public works projects predicated on ARRA funding already have begun.

- The economics of state allocations

- How are stimulus funds allocated to states?

- Are needy states getting more of the money?

- Conclusion

- References

The American Recovery and Reinvestment Act of 2009 (ARRA) was signed into law on February 17, and already its impact is being felt in state capitals around the nation. Governors and state legislators are incorporating expected stimulus funds into 2009-2010 budgets and a number of state public works projects predicated on ARRA funding already have begun. As states start spending these ARRA funds, the debate about their likely economic impact has taken on new life.

One question is whether federal stimulus funds are heading to those states best positioned to put the money to good use right away. That is, have the funds been allocated in a way that maximizes their potential impact on national economic growth? This Economic Letter addresses this question by comparing the degree of economic need in different states with each state’s expected share of ARRA funds. Such an analysis is important in evaluating the likelihood that stimulus money will be spent effectively. While it is too early to tell whether the overall stimulus package will have its intended effects, this review suggests that, by and large, the distribution of federal stimulus funds is indeed tilted toward those states most likely to spend the funds quickly and effectively.

The economics of state allocations

Of the $787 billion in ARRA, state governments will receive as much as $300 billion. The bulk of these state funds will be spread over four key programs:

- A $54 billion Fiscal Stabilization Fund meant primarily to stave off cuts in state education spending

- A $90 billion Fiscal Relief Fund meant to shore up financing for state Medicaid programs

- A $40 billion program to allow states to extend and increase unemployment insurance (UI) benefits

- At least $70 billion to fund transportation projects

The money going to states is meant to reduce their need to raise taxes or cut government spending to meet their constitutional balanced-budget requirements. According to ARRA proponents, such fiscal austerity could intensify the contraction of the national economy (see, e.g., Romer 2009).

The total impact of ARRA money going to states will depend on how quickly and productively states use the funds. How a given state spends its ARRA allocation will depend importantly on two factors: the restrictions tied to the use of the funds and the state’s budget position. For unrestricted funds, states facing more severe budget deficits will probably spend the money quickly. States in stronger fiscal health, however, potentially could receive more unrestricted money than they need to fund planned obligations and might save the excess by adding to their rainy day funds or transferring it to residents in the form of tax cuts. A good indicator then of how likely a state is to spend unrestricted federal funds immediately is its projected near-term budget deficit. I look at the relationship between state ARRA allocations and projected state budget gaps below.

For restricted funds, such as money earmarked for specific transportation projects, a different question is in order: Will these new public investments crowd out potential private investment, as some have argued (e.g., Becker and Murphy 2009), by drawing away productive resources such as capital and labor? The closer a state’s economy is to operating at capacity, the greater the potential for such crowding out. Below I also analyze whether ARRA’s transportation spending is expected to go disproportionately to states with the greatest idle productive capacity, which would reduce the potential for crowding out.

How are stimulus funds allocated to states?

The way in which ARRA funds will be distributed to states differs for each component of the stimulus package. For the $40 billion UI component, the federal government will almost fully reimburse each state’s cost of expanding and extending unemployment benefits. Hence, these funds will be allocated roughly in proportion to state unemployment rates. The other three ARRA state programs cited above are allocated according to formulas specified in the legislation, though each program also includes a small portion to be allocated at the discretion of the executive branch. The Fiscal Stabilization Fund, which is meant to prevent cuts in state education spending, uses the simplest of the three formulas. Aside from a small portion set aside for incentive grants, program funds will be allocated to each state according to a weighted average of its total population and its school-age population.

The Fiscal Relief Fund piggybacks on the existing formula for federal government assistance to state Medicaid programs and has three parts. The first is a simple scaling up of the existing federal share of a state’s Medicaid costs. Second, a so-called “hold-harmless” component is meant to offset cuts in federal support called for by the existing formula in states where per capita income grew rapidly in the last few years prior to the start of the recession. The third part provides for an additional increase in a state’s federal Medicaid share in proportion to the rise in the state’s unemployment rate during the recession. Taken together, the Fiscal Relief Fund’s three components direct the most support to states that have experienced the most rapid reversals in economic fortunes, where strong pre-recession economic growth was followed by rapidly rising unemployment and expanding Medicaid rolls.

The Fiscal Stabilization and Fiscal Relief Funds are partially restricted. They are meant to enable states to maintain spending on Medicaid and education above minimum thresholds laid out in the legislation. However, once a state has met those minimum requirements, stimulus funds from these two programs allow the state to shift resources to other parts of its budget. For practical purposes, these funds are largely unrestricted.

Are needy states getting more of the money?

Earlier I suggested that a reasonable indicator of how likely a state is to spend unrestricted ARRA funds immediately is its projected budget deficit. So one test of the legislation’s potential impact is whether states with bigger projected budget gaps are likely to receive disproportionate shares of the Fiscal Stabilization and Fiscal Relief Funds, the primary sources of unrestricted state money in ARRA. To answer this, I look at the Center on Budget and Policy Priorities data on projected state fiscal 2010 budget gaps, as well as the Center’s estimates of state Fiscal Stabilization and Fiscal Relief Fund allocations. The budget gap data are based on state reports forecasting the difference between revenue and spending, assuming no change in current state laws.

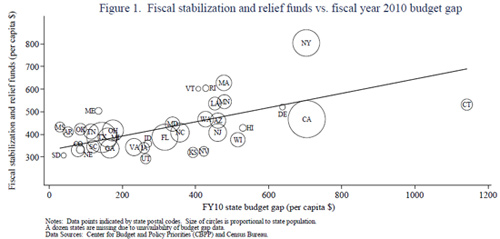

Figure 1 shows a scatter plot depicting the relationship between these projected budget gaps and the expected allocations of Fiscal Stabilization and Fiscal Relief Funds. Each point in the plot represents a state, identified by its postal code. Its placement along the horizontal axis indicates its per capita budget gap. Its placement along the vertical axis represents the per capita funds it is expected to receive. The size of the circle for each state is proportional to its population. Finally, the line running through the data points depicts the relationship between the two series as estimated by population-weighted ordinary least squares regression, a statistical technique for measuring correlation.

The figure clearly shows a strong positive correlation between a state’s degree of fiscal strain and the amount of federal stimulus funds it is expected to receive. A separate analysis indicates that this positive relationship largely reflects the allocation of Fiscal Relief Funds, rather than Fiscal Stabilization Funds. This is not surprising. Recall that the majority of the $54 billion Stabilization Fund is allocated to each state based on a weighted average of its total population and its school-age population. This means the per capita allocation of the Fund will be in proportion to the school-age share of a state’s total population. Of course, there’s little reason to expect these youth shares of the population to be correlated with projected budget deficits, and in fact they are not. And recall that the allocation of the $90 billion Fiscal Relief Fund favors states that experienced rapid economic growth leading up to the recession followed by steep declines during the recession. Such reversals of fortune also take a heavy toll on state budgets, so it’s not surprising that the Fiscal Relief funds are strongly correlated with these budget gaps.

I turn next to the issue of whether the impact of the restricted funds ARRA distributes to states could be hindered by crowding out of private-sector resources. Specifically, I assess whether transportation funds, the program’s largest source of restricted funds, will be allocated disproportionately to those states most likely to have idle capacity, especially unemployed labor. The bulk of ARRA’s transportation funds is expected to be allocated using the same formulas that the Department of Transportation (DOT) uses to distribute non-ARRA highway and other transportation funds to states. These formulas are based on factors such as a state’s total highway miles, and needed repairs to roads and bridges previously identified by DOT. They are not designed to account for a state’s economic condition, and there is no reason to expect a positive relationship between expected per capita ARRA transportation funds and unemployment rates. Data from the National Conference of State Legislatures and the Bureau of Labor Statistics confirm the absence of a positive correlation. In fact, a slight negative correlation exists, since less densely populated states tend to have more highway miles per capita. In addition, low-population-density states tend to be in better fiscal shape during this downturn, thanks largely to booms in their natural resources industries in recent years.

From the standpoint of maximizing the national economic impact of the stimulus package, this distribution of transportation spending clearly appears less than optimal. However, all states have seen substantial increases in their unemployment rates since the start of the recession, so it’s hard to argue that any state currently is at full employment and does not have idle capacity that can be put to use on major construction projects.

As far as maximizing its impact on national economic growth, ARRA’s allocation across states clearly is not perfect. The transportation funds are skewed toward states with lower unemployment rates, albeit rates above full employment levels. The Fiscal Stabilization Fund is distributed to states based on the age composition of each state’s population, which turns out, not surprisingly, to be unrelated to state fiscal health.

The Fiscal Relief Fund, however, appears to be well-targeted because it is geared toward those states with the most serious fiscal strains. And the sheer magnitude of the $90 billion fiscal relief program is enough to ensure that ARRA fiscal aid funds will in aggregate be allocated to those states most likely to spend the money quickly. What’s more, aid provided to states to fund additional unemployment insurance benefits is directly aimed at getting money into the hands of unemployed people, who are generally considered to have high propensities to spend rather than save.

So, while ARRA’s state allocations do not represent the absolute optimal stimulus, they are on the whole well directed. Overall, that means that the economic impact of this support for state governments is more likely to exceed than to fall short of forecasts.

Daniel Wilson

Senior Economist

Becker, Gary S., and Kevin M. Murphy. 2009. “There’s No Stimulus Free Lunch.” Wall Street Journal Op-Ed, Feb. 10.

Romer, Christina. 2009. “The Case for Fiscal Stimulus: The Likely Effects of the American Recovery and Reinvestment Act.” Speech delivered at Brookings Institution, Feb. 27.

Opinions expressed in FRBSF Economic Letter do not necessarily reflect the views of the management of the Federal Reserve Bank of San Francisco or of the Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System. This publication is edited by Anita Todd and Karen Barnes. Permission to reprint portions of articles or whole articles must be obtained in writing. Please send editorial comments and requests for reprint permission to research.library@sf.frb.org