As the U.S. housing market has moved from boom in the middle of the decade to bust over the past two years, the sources of mortgage funding have changed dramatically. The government-sponsored enterprises—Fannie Mae, Freddie Mac, and Ginnie Mae—now own or guarantee an overwhelming share of originations. At the same time, non-agency mortgage securitization and loans retained in lender portfolios have largely dried up.

The period following the 2001 recession through 2006 is rightly called a housing boom. House prices and net borrowing by households surged in the early part of the decade, easily outpacing growth in household income. But, with the onset of the financial crisis and the failure of many mortgage market participants, access to mortgage finance declined dramatically. This Economic Letter summarizes some of the key ways that the mortgage market evolved during the boom years and during the ensuing housing market bust. It focuses on changes in the way loans were made and funded and how loan characteristics themselves changed.

Sources of mortgage finance

One of the distinguishing features of the U.S. housing finance system is the role played by the capital markets in funding residential mortgages (see Green and Wachter 2007). The direct link between housing finance and the capital markets is through securitization of home loans in various types of mortgage-backed securities (MBS). The pooling of mortgages into MBS permits the separation of loan origination and funding, as well as the transfer of risk. Also, depending on the type of MBS, securitization can facilitate the separation of credit risk—the possibility that borrowers default on their mortgages—and market risk, defined as changes in the value of a portfolio of mortgages as interest rates move and borrowers prepay. Securitization transforms relatively illiquid loans into highly liquid securities. In addition, pooling mortgages from different geographic regions serves as a way for investors to diversify away from shocks to local housing markets.

With the development of MBS and other types of structured financial products, banking institutions, including commercial banks, savings institutions, and credit unions, have slowly but steadily ceded market share to capital market investors in holding residential mortgage assets in portfolio. According to Federal Reserve flow of funds data, the banking institution share of total mortgage assets declined from a peak of about 75% in the mid-1970s to about 35% in 2008. Much of the decline in banking institution housing portfolios over this period was related to the expansion of the government-sponsored enterprises (GSEs) Fannie Mae, Freddie Mac, and Ginnie Mae. The GSEs purchase mortgages for securitization and guarantee MBS against credit risk.

Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac require that mortgages conform to certain standards to qualify for securitization. For example, mortgages must meet set size limits and underwriting guidelines. Ginnie Mae guarantees the repayment of principal and interest on MBS backed by federally insured loans, such as Federal Housing Administration (FHA) or Department of Veterans Affairs loans. Unlike Fannie Mae or Freddie Mac, Ginnie Mae is explicitly backed by the U.S. government.

Starting in the late 1990s, the GSEs’ near-exclusive hold on residential MBS issuance was challenged by so-called non-agency, or private-label, securities issued by brokerage firms, banks, and even homebuilders. Non-agency securitizations are conceptually very similar to agency securitizations. Lenders sell loans to an arranger, which then packages the loans, creates securities with claims to the cash flows of the loans, and sells the securities to investors (see Bruskin, Sanders, and Sykes 2000). However, in contrast to agency MBS, purchasers of non-agency securities are exposed to credit risk as well as market risk. Also, non-agency securitizations are more complex, involving many specialized parties. In recent years, securities were typically separated into tranches and structured to create different payoffs—more complicated arrangements than typical of agency securitizations. At its peak in late 2007, non-agency securitizations accounted for nearly 20% of outstanding mortgage credit.

An avalanche of research and commentary has examined why non-agency securitization grew so fast during the housing boom. One argument suggests that policymakers were worried that the GSEs were becoming too big and systemically important. These fears led to the imposition of caps on GSE portfolios, giving a boost to alternative sources of mortgage funding as the demand for housing finance boomed. Another story points to the decline in economic and financial market volatility that took place in the 1990s, especially in the first part of the decade. This phenomenon may have led to an increase in lending to previously marginal borrowers—a development that was probably not unique to mortgages but occurred in other asset markets as well.

Loans and loan characteristics, then and now

As noted above, GSE securitization involves loans that conform to size and underwriting guidelines. Mortgages that found their way into private securitizations were nonconforming according to one or more of these criteria. Differences in the characteristics of GSE and non-agency mortgages are observable in the data collected by LPS Applied Analytics, which tracks loan terms and performance as reported by mortgage servicers. LPS collects data from nine of the top ten mortgage servicers, accounting for approximately 60% of the total residential mortgage market.

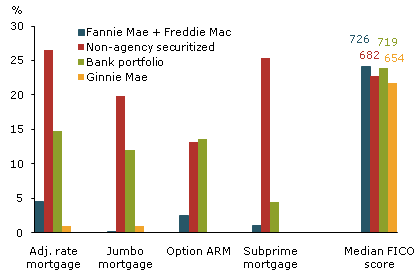

Figure 1

Mortgage characteristics, 2006

Source: LPS Applied Analytics.

Figure 1 shows some of the important differences between GSE-owned or guaranteed mortgages and mortgages that were securitized through non-agency channels or retained in the original lender’s portfolio. The data are from 2006, the peak year for non-agency securitizations. Compared with mortgages purchased by the GSEs, non-agency securitizations were much more likely to involve adjustable-rate mortgages, including option ARMs, to be rated as subprime, and to have less-than-full documentation of borrower income and assets. The median FICO credit score for the non-agency securitizations was about 30 points lower than for the mortgages held or guaranteed by Fannie Mae or Freddie Mac and much closer to the credit scores typically associated with loans guaranteed by Ginnie Mae. Compared with Ginnie Mae, however, the non-agency securitizations tended to involve a much greater share of adjustable-rate mortgages. Indeed, in 2006, non-agency securitizations appear to have gained market share by partially displacing Ginnie Mae’s position among borrowers with low credit quality and expanding into the market for jumbo loans, which exceed GSE size limits.

Regional patterns in growth of non-agency MBS

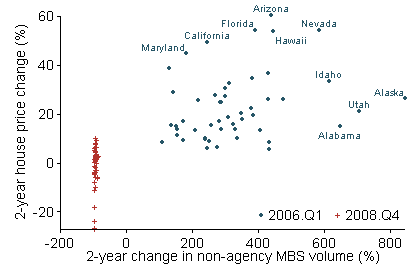

Figure 2

Regional changes in mortgage market structure

Figure 2 provides regional detail on how mortgage lending funded by non-agency MBS evolved over the decade. The data here are based on two-year changes in loan origination volumes calculated at two points in time: the boom from the first quarter of 2004 through the first quarter of 2006, and the bust from the fourth quarter of 2006 through the fourth quarter of 2008. I include both purchase loans and refinances, as well as first-lien mortgages and second liens on owner-occupied properties.

The figure reveals a suggestive correlation between growth in mortgage finance and growth in house prices during the boom years. States with the highest proportions of mortgages subject to non-agency securitization tended to experience more pronounced price appreciation. It may have been that lenders and investors expected house prices to continue to rise in these fast-growing states and consequently became relatively less averse to the risk of lending. Indeed, if house prices were expected to keep climbing, default risks on mortgages would be expected to fall, holding all else constant. The reverse story is more controversial, namely that the growth in credit availability spurred by non-agency securitization actually may have helped fuel house price appreciation (see Mian and Sufi 2009.

In the bust period after the boom, house prices have fallen sharply and lending supported by private-label securities has greatly diminished. Apparently, the retreat of lenders and investors from the nonconforming segment of the market has less to do with the fundamentals in regional housing markets and more to do with a system-wide shock.

Rise and fall of non-agency securitization

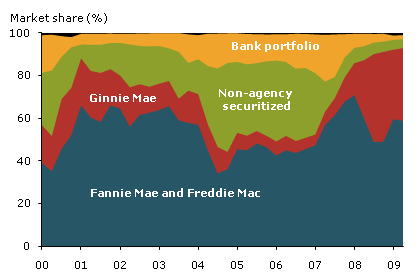

Figure 3

Investor type shares of new loan originations

Note: Black area refers to “other.”

As noted above, the sources of mortgage finance have shifted as the housing market has gone from boom to bust. Figure 3 plots the evolution of these funding sources over the past decade. Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac combined have consistently been the largest players in the market, owning or guaranteeing about half or more of the mortgages in the sample at any given time. Non-agency securitization peaked in the first quarter of 2006, when it accounted for nearly 40% of new originations. Finally, the share of mortgages retained in the originating institution’s portfolio averaged about 15% throughout the boom, but has fallen considerably since.

The most noticeable feature of Figure 3 is the abrupt change in financing patterns beginning in the middle of 2007. This period, of course, marks the onset of the financial crisis and the contraction of nonconforming loan originations. Figure 3 shows dramatic declines during this time in both non-agency securitization and originations of loans retained in the lending institution’s portfolio. In the present day, when Ginnie Mae’s activities are included, the three GSEs are providing unprecedented support to the housing market—owning or guaranteeing almost 95% of the new residential mortgage lending.

This shift in mortgage finance has had a profound impact on the types of borrowers receiving loans. In the fourth quarter of 2006, approximately 10% of originations in our sample were labeled by originators as “subprime.” For the entire universe of mortgages, subprime loans are estimated to have made up about 20% of originations in 2006. By the first quarter of 2008, the subprime share was effectively zero. Since then, increased FHA lending—identified here by Ginnie Mae’s share—has revived this segment of the market. After plummeting in early 2008, the share of borrowers with FICO credit scores lower than 660 has returned to just higher than 20%, the same share as when subprime securitization peaked in 2006.

The collapse of nonconforming loan originations has had a particularly strong impact on the higher end of the market. The share of jumbo mortgages was nearly 9% at the peak in 2006. By the end of 2008, jumbo loans accounted for just 3% of new originations. Meanwhile, in another big shift, option ARMs made up about 6% of originations in the fourth quarter of 2006. By year-end 2008, option ARMs had vanished from the data set.

Conclusion

Mortgage originations have slowed considerably over the past two years. According to Federal Reserve flow of funds data, household net borrowing backed by home mortgages has fallen every quarter since the beginning of 2006, and is now negative for the first time since the 1970s. It is difficult to disentangle the role played by declining demand for mortgages from the declining supply of credit. Lender surveys, such as the Federal Reserve Senior Loan Officer Opinion Survey, have consistently reported that borrower demand has declined over the course of the recession. Credit supply problems, however, still appear to be a major problem affecting the housing market. With the vast majority of current mortgage lending now intermediated in some form by the GSEs, it will be difficult for the housing market to return to normal.

References

Bruskin, Eric, Anthony Sanders, and David Sykes. 2000. “The Nonagency Mortgage Market: Background and Overview.” In The Handbook of Nonagency Mortgage-Backed Securities, 2nd edition, eds. Frank Fabozzi, Chuck Ramsey, and Michael Marz. Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons.

Green ,Richard, and Susan Wachter. 2007. “The Housing Finance Revolution.” Prepared for the 31st Economic Policy Symposium: Housing, Housing Finance & Monetary Policy.

Mian, Atif, and Amir Sufi. 2009. “The Consequences of Mortgage Credit Expansion: Evidence from the U.S. Mortgage Default Crisis.” Quarterly Journal of Economics 124(4, November).

Opinions expressed in FRBSF Economic Letter do not necessarily reflect the views of the management of the Federal Reserve Bank of San Francisco or of the Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System. This publication is edited by Anita Todd and Karen Barnes. Permission to reprint portions of articles or whole articles must be obtained in writing. Please send editorial comments and requests for reprint permission to research.library@sf.frb.org