Household leverage in the United States and many industrial countries increased dramatically in the decade prior to 2007. Countries with the largest increases in household leverage tended to experience the fastest rises in house prices over the same period. These same countries tended to experience the biggest declines in household consumption once house prices started falling.

“[O]ver-investment and over-speculation are often important; but they would have far less serious results were they not conducted with borrowed money.” —Irving Fisher (1933)

In the United States and many other industrial countries, the recent financial crisis contributed to the longest and most severe economic contraction since the Great Depression. The rapid expansion in the use of borrowed money, or leverage, by households in recent years, is one factor that may help account for the virulence of the downturn.

In the years leading up to the crisis, a combination of factors, including low interest rates, lax lending standards, a proliferation of exotic mortgage products, and the growth of a global market for securitized loans fueled a rapid increase in household borrowing. An influx of new and often speculative homebuyers with access to easy credit helped bid up U.S. house prices to unprecedented levels relative to rents or disposable income. U.S. household leverage, as measured by the ratio of debt to personal disposable income, reached an all-time high, exceeding 130% in 2007 (see Glick and Lansing 2009). National house prices peaked in 2006 and have since dropped by about 30%. The bursting of the housing bubble set off a chain of events that pushed the U.S. economy into a severe recession that started in December 2007.

This Economic Letter shows that the recent U.S. experience is by no means unique. Household leverage in many industrial countries increased dramatically in the years prior to 2007. Countries with the largest increases in household leverage tended to experience the fastest rise in house prices over the same period. Moreover, these same countries tended to experience the most severe declines in consumption once house prices started falling. The common patterns observed across countries suggest that, as in the United States, the unwinding of excess household leverage via increased saving or increased default rates could be a significant drag on consumption and bank lending going forward, possibly muting the vigor of the economic recovery.

Household leverage and consumption: U.S. county data

The typical residential housing transaction is financed largely with borrowed money. The use of such leverage to purchase an asset magnifies the risk assumed by the buyer. If the value of the asset subsequently drops, as in a burst bubble, the debt incurred to buy the asset remains in place and the buyer must still repay the loan in full. If the debt exceeds the asset’s market value, refinancing options are limited. If the debt is very large relative to the buyer’s income, repayment can strain the buyer’s finances, forcing a reduction in other spending. And if the strain becomes too great, the buyer may be forced to default, shifting some or all of the loss to the lender or the taxpayer if the loan is government-insured.

Using data on household borrowing for the 450 largest U.S. counties by population, Mian and Sufi (2009a,b) provide evidence that the rapid rise in household leverage in recent years was a primary driver of the recession that began in December 2007. Their analysis identifies several important patterns. First, they find that house prices rose faster in areas where subprime mortgages were more prevalent. This suggests the existence of a self-reinforcing feedback loop in which new buyers with access to easy mortgage credit helped fuel the run-up in prices by bidding competitively for houses, which in turn encouraged lenders to ease credit even further based on the assumption that house prices would continue to appreciate indefinitely. Second, the authors find that for each incremental dollar of house price appreciation, the average homeowner extracted about 25 to 30 cents in cash via home equity borrowing, which was used primarily for consumption or home improvement. This indicates that house price appreciation fueled by easy mortgage credit was a significant driver of economic growth during the boom years. Third, they find that counties that experienced the largest increases in leverage tended to experience the sharpest rise in loan defaults and the most severe recessions, where severity is measured by the subsequent fall in consumption of durable goods or the subsequent rise in the unemployment rate. The last point suggests that recession severity in a given area reflects the degree to which prior growth there was driven by an unsustainable borrowing trend–one which came to an abrupt halt once house prices stopped rising.

Household leverage and consumption: International data

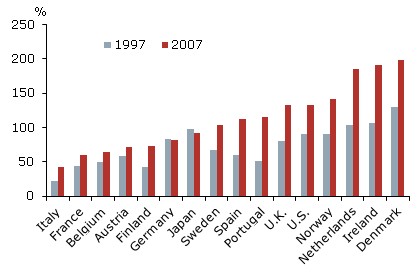

Figure 1

Household leverage ratios: Debt to disposable income

Note: The following countries use different data years: Japan 1997, 2006;Spain 2000, 2007; Ireland 2002, 2007.

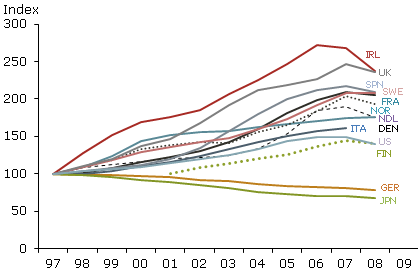

Figure 2

Real house prices, 1997-2008

Note: All series are indexed to 100 in 1997 except Finland, which is indexedto 100 at 2001.

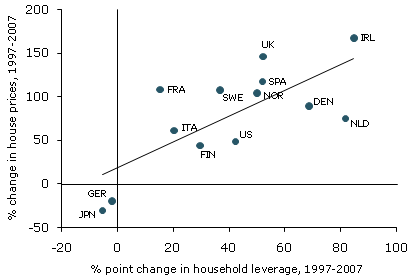

Figure 3

Household leverage and the run-up in house prices

Note: The plotted line depicts the best fit relationship in the data asgenerated by a simple least square statistical regression.

Figure 4

Household leverage and the decline in consumption

Note: The plotted line depicts the best fit relationship in the data asgenerated by a simple least square statistical regression.

As in the United States, household borrowing in many industrial countries grew rapidly in the years leading up to the financial crisis. Figure 1 depicts the increase in the household leverage ratio, defined as household debt as a percent of disposable income including transfers, in the United States and 15 other industrial countries over a 10-year period ending in 2007, according to data from the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development. Compared to the U.S. household leverage ratio of around 130% in 2007, leverage ratios were significantly higher in some countries, including Denmark (199%), Ireland (191%), and Netherlands (185%), but lower in others, such as Italy (43%), France (60%), Belgium (64%), and Germany (82%).

From 1997 to 2007, the U.S. household leverage ratio rose by 42 percentage points. Other countries experienced a greater increase in household leverage over the same period, including Ireland (+85 points), Netherlands (+82 points), Denmark (+69 points), Portugal (+65 points), Spain (+52 points), United Kingdom (+52 points), and Norway (+50 points). At the other end of the spectrum, leverage ratios rose only modestly in Austria (+13 points), Belgium (+14 points), and France (+15 points), while they actually declined in Germany (-2 points) and Japan (-5 points).

Figure 2 plots the trajectory of real house prices in the United States and other industrial countries since 1997. Austria, Belgium, and Portugal are omitted due to lack of data. Real house prices in the United States rose by roughly 50%, reaching a peak in 2006. House prices in other industrial countries also rose substantially and in most cases more than in the United States. At their peaks, prices rose the most in Ireland (172%), United Kingdom (146%), Spain (118%), and France and Sweden (108%), followed by Denmark, (89%), Netherlands (75%), and Italy (61%). These dramatic run-ups, which far exceeded the growth in disposable incomes over the same period, show that housing bubbles were widespread. The two exceptions were Japan and Germany, where real house prices fell over this period. However, both countries had previously experienced large run-ups in house prices during the late 1980s and early 1990s.

Figure 3 combines data from Figures 1 and 2. The scatter plot shows that countries exhibiting the largest increases in household leverage from 1997 to 2007 also tended to experience the fastest rise in house prices over same period. The pattern suggests that the link between easy mortgage credit and rising house prices held on a global scale.

Figure 4 shows that countries experiencing the largest increases in household leverage before the crisis tended to experience the most severe recessions, where severity is measured by the percentage decline in real consumption from the second quarter of 2008 to the first quarter of 2009. Consumption fell most sharply in Ireland (-6.7%) and Denmark (-6.3%), both of which saw huge increases in household leverage prior to the crisis. Consumption was flat or fell only slightly in Germany, Austria, Belgium, and France, which were among the countries that saw the smallest increases in household leverage before the crisis. Overall, the data suggest that recession severity in a given country reflects the degree to which prior growth was driven by an unsustainable borrowing trend. Of course, other factors besides leverage could have influenced the post-crisis consumption pattern. These include actions taken by policymakers in the respective countries to mitigate the economic fallout from the financial crisis.

Interestingly, King (1994) identifies a similar correlation between prior increases in household leverage ratios and the severity of the early 1990s recession using data for 10 major industrial countries from 1984 to 1992. Reviewing earlier historical episodes, he also notes that U.S. consumer debt more than doubled during the 1920s–a factor that probably contributed to the severity of the Great Depression in the early 1930s.

Conclusion

Going forward, the efforts of households in many countries to reduce their elevated debt loads via increased saving could result in sluggish recoveries of consumer spending. Higher saving rates and correspondingly lower rates of domestic consumption growth would mean that a larger share of GDP growth would need to come from business investment, net exports, or government spending. Debt reduction might also be accomplished via various forms of default, such as real estate short sales, foreclosures, and bankruptcies. But such deleveraging involves significant costs for consumers, including tax liabilities on forgiven debt, legal fees, and lower credit scores.

As countries begin to emerge from the recession, it is important to consider what lessons might be learned for the conduct of policy. History suggests that asset price bubbles can be extraordinarily costly when accompanied by significant increases in borrowing. During the recent housing bubble, underwriting standards were weakened and credit extension rose at abnormally high rates, creating a self-reinforcing feedback loop that drove house prices upward. In the aftermath of a global boom-and-bust cycle in credit and housing, financial regulators should take the necessary steps to prevent a replay of this damaging episode.

References

Fischer, Irving. 1933. “The Debt-Deflation Theory of Great Depressions.” Econometrica 1, pp. 337-357.

Glick, Reuven, and Kevin J. Lansing. 2009. “U.S. Household Deleveraging and Future Consumption Growth.” FRBSF Economic Letter 2009-16 (May 15).

King, Mervyn. 1994. “Debt Deflation: Theory and Evidence.” European Economic Review 38, pp. 419-445.

Mian, Atif, and Amir Sufi. 2009a. “The Consequences of Mortgage Credit Expansion: Evidence from the U.S. Mortgage Default Crisis.” Quarterly Journal of Economics, forthcoming.

Mian, Atif, and Amir Sufi. 2009b. “Household Leverage and the Recession of 2007 to 2009.” University of Chicago, Booth School of Business Working Paper.

Opinions expressed in FRBSF Economic Letter do not necessarily reflect the views of the management of the Federal Reserve Bank of San Francisco or of the Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System. This publication is edited by Anita Todd and Karen Barnes. Permission to reprint portions of articles or whole articles must be obtained in writing. Please send editorial comments and requests for reprint permission to research.library@sf.frb.org