The European Central Bank recently raised its target interest rate for the first time since the 2008 financial crisis. When compared with a simple interest rate rule, this rate hike appears consistent with the euro area’s nascent economic recovery and rising inflation. However, economic conditions vary greatly among the countries in the euro area and the ECB’s new target rate may not be suitable for all of them.

During the 2008 financial crisis, several central banks, including the European Central Bank (ECB), reduced their target rates to historically low levels in response to deteriorating economic conditions, including rising unemployment and severe disruptions in financial markets. Recently, the ECB reversed course. At its April 2011 meeting, it announced the first increase in its target rate since the crisis, a 0.25 percentage point (25 basis points) rise to 1.25%. Given the economic turmoil in several countries of the European periphery, the question is how this increase might affect different euro-area members. This Economic Letter looks at the ECB move in the context of a Taylor rule, a widely used guideline for monetary policy rates. A standard Taylor rule is applied to the euro area and its member countries, and the policy rates predicted by this rule are compared with the ECB’s target rate path.

Euro-area Taylor rule recommendation

The Taylor rule is a policy guideline that generates recommendations for a monetary authority’s interest rate response to the paths of inflation and economic activity (Taylor 1993). According to one version of this rule, policy interest rates should respond to deviations of inflation from its target and unemployment from its natural rate (Rudebusch 2010). A simple version of this rule is:

Target rate = 1 + 1.5 x Inflation – 1 x Unemployment gap.

The target rate recommended by the rule is a function of the inflation rate and the unemployment gap. That gap is defined as the difference between the measured unemployment rate and the natural rate, that is, the unemployment rate that would cause inflation neither to decelerate nor accelerate. The literature shows that this simple rule or close variations approximate fairly well the policy performance of several major central banks in recent years (see Taylor 1993 and Peersman and Smets 1999).

To analyze recent ECB interest rate movements, I apply the version of the Taylor rule described above to the euro area’s unemployment gap and inflation. I then compare the target rate recommended by the Taylor rule with the ECB’s actual policy rate. For comparison, I do a similar exercise for the Federal Reserve.

To generate Taylor rule policy rates for both the United States and the euro area, I use measured rates of unemployment and natural unemployment rates estimated by the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD). I use core inflation rates, which exclude volatile energy and food prices. U.S. researchers frequently use core inflation because it tends to predict medium-term inflation better than headline inflation. To make results comparable, I also use core inflation for the euro area and its member countries. The ECB explicitly focuses on headline inflation, so I perform the same exercise with that measure. With both core and headline inflation, the results are qualitatively unchanged.

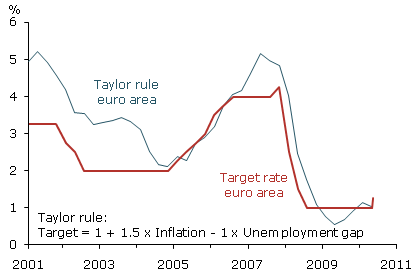

Figure 1

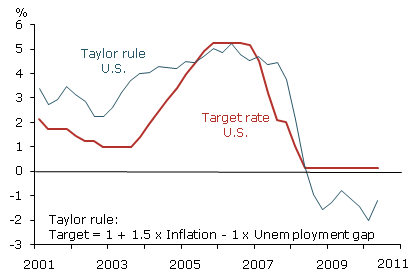

Taylor rule recommendations and target rates

A. Euro area (quarterly average)

B. United States (quarterly average)

Sources: Eurostat, OECD.

Figure 1A compares policy rates recommended by the Taylor rule for the euro area over time with the actual target rates set by the ECB. It shows that, since 2005, the actual target rate has generally closely matched the rate recommended by the Taylor rule. In particular, the ECB’s recent policy rate increase was in line with the Taylor rule recommendation. Figure 1B shows the same exercise for the United States. It indicates that, since 2005, the actual U.S. policy rate has also generally lined up with the Taylor rule prediction. However, the United States has recently deviated from the Taylor rule, which since 2008 has recommended a negative interest rate target. Negative nominal interest rates are not practical possibilities, so the actual target rate has had to stay near its lower bound of zero.

Core inflation levels in the United States and the euro area have been similar. But the U.S. unemployment gap is about twice as large as the euro area’s gap, a sign that the European economy is recovering faster from recession than the U.S. economy. The larger U.S. unemployment gap is the main reason why the Taylor rule policy rate recommendation for the United States is lower than its recommendation for the euro area.

Although Taylor rule recommendations for the euro area have been consistent with the ECB’s target rate movements since 2005, the question remains as to what rates the Taylor rule recommends for individual euro-area member countries. In fact, inflation rates and, more importantly, national economic output and unemployment vary significantly within the euro area. If macroeconomic conditions are different among member countries, then Taylor rule recommendations may also vary. In particular, the Taylor rule may suggest lower target rates for the so-called peripheral countries that have been caught in the sovereign debt crisis.

Periphery versus core

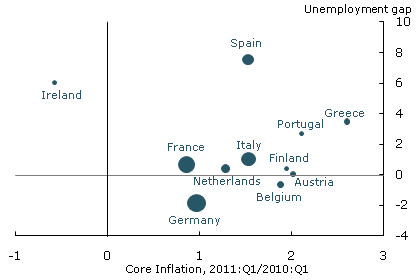

Figure 2

Euro-area unemployment gap and core inflation

Sources: International Monetary Fund and OECD.

Notes: Size of dots indicate country share of total euro-area GDP. OECD provides only the nonaccelerating inflation rate of unemployment for the above countries in the euro area.

Figure 2 shows core inflation rates and unemployment gaps for selected euro-area countries, along with their relative size in the area. The figure illustrates a marked divergence between the peripheral countries of Greece, Ireland, Portugal, and Spain and the so-called core European countries of Austria, Belgium, France, Finland, Germany, and the Netherlands. Germany’s economy is booming, while Spain has an unemployment gap of almost 8 percentage points. Overall, the peripheral countries have much higher unemployment gaps than the core countries. At the same time, inflation varies significantly in the peripheral countries.

A simple Taylor rule could be applied to each euro-area country individually to generate a policy interest rate recommendation for that country. However, for simplicity, I designate member countries as part of either the euro area’s core or periphery. I then look at Taylor rule interest rate recommendations for those two groups. Each country is weighted according to the size of its real GDP. The peripheral group is made up of Greece, Ireland, Portugal, and Spain, while the core group consists of the previously mentioned core countries plus Italy. Although Italy is often categorized as a peripheral country, its inflation rate and unemployment gap are more comparable to the euro area’s core countries.

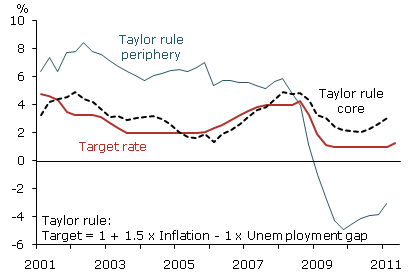

Figure 3

Policy rules: Periphery vs. core (quarterly average)

Sources: Eurostat, OECD.

Figure 3 compares the paths of rates recommended by the Taylor rule for the euro area’s core and periphery with the actual ECB policy target rate. As noted earlier, the ECB’s actual target rate seems to be in line with the Taylor rule recommendation for the euro area as a whole. But things look very different when the Taylor rule is applied separately to the euro area’s core and periphery. The policy target rate recommended by the Taylor rule for the peripheral countries remains negative. The ECB’s actual policy rate is well above the rate recommended by the Taylor rule for the periphery, but below the Taylor rule recommendation for the core. This is not surprising. The core countries are well along the path of economic recovery. But the peripheral countries are still struggling to recover from the sovereign debt crisis. They are implementing a range of reforms and fiscal adjustments, which have impeded overall economic recovery (see Nechio 2011). It is uncertain whether the peripheral countries will be able to grow fast enough to generate the income they need to service their sovereign debt obligations. Increases in interest rates may make reaching such growth levels even more challenging.

Strikingly, Figure 3 shows that a divergence between the ECB’s actual target rate and the rate recommended by the Taylor rule for the peripheral countries is not new, but has reversed itself. Before the 2008 crisis, the ECB target rate lay below the level predicted by the Taylor rule for the peripheral countries. In fact, from the inception of the euro to the 2008 financial crisis, the actual ECB policy rate was below the rate predicted by the Taylor rule for the peripheral countries and more in line with Taylor rule recommendations for the core euro-area countries. During the financial crisis in 2008, the peripheral countries fell into deep recession, which was followed by a debt crisis from which they have yet to recover. By contrast, recovery in the euro-area core has been more robust. These events reversed the historic pattern and positioned the ECB policy rate above the Taylor rule recommendation for the peripheral countries.

Conclusion

When members of a monetary union are experiencing different macroeconomic conditions, a single policy rate is unlikely to fit circumstances in all countries. Currently, the ECB’s target rate seems to be in line with a Taylor rule recommendation for the euro area as a whole. However, economic differences between peripheral and core euro-area countries are sharp. The core countries are recovering, while the peripheral countries still have large unemployment gaps. Thus, the ECB target rate is not in line with Taylor rule recommendations for the peripheral countries.

For the euro area as a whole, the Taylor rule fit has been quite good since 2005, as it has been for the United States. This is not to say that the Taylor rule necessarily indicates optimal policy. Rather, it can be viewed as a “rule of thumb” that has matched ECB policy well over some periods. But the wide gaps in the Taylor rule’s current recommendations for the euro area’s core and periphery show that one size cannot fit all when economic conditions in two regions of a monetary union are so markedly different.

The euro area’s problem of a “one-size-fits-all” monetary policy is not unique. In the United States, economic conditions have frequently differed dramatically across regions. The Federal Reserve does not set different monetary policies for different parts of the country. Nevertheless, the tensions over monetary policy in a union of many separate countries are likely to be greater than tensions in a single country. The United States can rely on its relatively high labor mobility and on fiscal policy to counter economic weakness, for example, options that may not be fully available to the euro area’s heavily indebted peripheral countries.

Reference

Nechio, Fernanda. 2011. “Long-Run Impact of the Crisis in Europe: Reforms and Austerity Measures.” FRBSF Economic Letter 2011-07 (March 7).

Peersman, Gert, and Frank Smets. 1999. “The Taylor Rule: A Useful Monetary Policy Benchmark for the Euro Area?” International Finance 2(1, April), pp. 85-116.

Rudebusch, Glenn. 2010. “The Fed’s Exit Strategy for Monetary Policy.” FRBSF Economic Letter 2010-18 (June 14).

Taylor John B. 1993. Macroeconomic Policy in a World Economy: From Econometric Design to Practical Operation. New York: W. W. Norton & Company.

Opinions expressed in FRBSF Economic Letter do not necessarily reflect the views of the management of the Federal Reserve Bank of San Francisco or of the Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System. This publication is edited by Anita Todd and Karen Barnes. Permission to reprint portions of articles or whole articles must be obtained in writing. Please send editorial comments and requests for reprint permission to research.library@sf.frb.org