Although bank small business loan portfolios continue to shrink, there are hints of possible stabilization. Among smaller banks, small business lending that is not backed by commercial real estate looks slightly healthier than small business lending that is secured by commercial property. Meanwhile, small commercial and industrial loans at larger banks are showing clear signs of a turnaround. Evidence from the 2001 recession as well as loan performance data suggest that small commercial and industrial loans at smaller banks may not be far behind.

Banks have pared their small business loan portfolios by over $47 billion since the pre-recession peak in 2007, with outstanding loans continuing to dwindle. In contrast, indirect evidence suggests that portfolios of loans to larger businesses have started growing again. The trends for small business loans are important because these enterprises play a vital role in the U.S. economy. Nonfarm businesses with fewer than 500 employees account for about half of private-sector output and employ more than half of private-sector workers. Moreover, relatively new businesses, most of which are small, generate a large share of new jobs.

In this Economic Letter, we investigate several small business lending trends, including a continuing shrinkage of bank loans in this category. However, the overall rate of decline may be easing. When we distinguish between large and small banks and between loans backed by commercial real estate and those not backed by commercial property, the signs are clearer of a possible move toward stabilization in small business lending.

Are bank loans important for small businesses?

About 93% of small businesses used some form of credit in 2003, according to that year’s Survey of Small Business Finances, the most recent survey in this series (Mach and Wolken 2006). Bank loans were not the only source of credit for such businesses. Many small businesses used other sources, such as trade credit, personal credit cards, or home equity loans. Still, about 60% used a bank loan as at least one of their sources.

Small banks may be particularly important for some types of small business credit. If a business has few assets or assets that are difficult to value as collateral, lender underwriting and monitoring must rely heavily on information about the borrower’s creditworthiness and the business’s ongoing prospects. Small businesses often do not have audited financial statements, so lenders frequently must rely on other information. Much of that information is most readily available locally. It might include knowledge about the local economy and community; the borrower’s industry, since some industries are concentrated locally or regionally; the borrower’s particular business; and the character, skills, and other personal attributes of the business owner or owners.

Berger, Klapper, and Udell (2001) argue that small banks have a comparative advantage over large banks in making such “relationship” loans, that is, loans that use this type of “soft” information. Soft information is more qualitative and subjective than “hard” information, such as financial statements, and may be relatively difficult to communicate. Assessments of the character of the business owner, a key element in many small business lending decisions, seems particularly subjective. In theory, both large and small local banks can easily obtain information about the business owner’s character. For example, loan officers may have repeated contacts with the borrower in both business meetings and informal social settings. However, loan officers at small banks may be able to use that information more easily than their counterparts at large banks because fewer layers of management are involved in lending decisions.

On the other hand, large banks may gain an edge with certain small businesses by using other approaches, such as asset-based lending, including lending on receivables, and small business credit scoring. Large banks have comparative advantages over small banks in these approaches. For example, they are better able to use small business credit scoring because of the extensive fixed costs associated with this method.

What do the data show?

Small business lending trends can be discerned from the data banks report in regulatory financial statements, known as Reports of Condition and Income, or Call Reports. We omit banks that specialize in either business or consumer credit card lending because the credit card market is so large that it can obscure trends in the small business lending types that are the focus here. We can measure the dollar volume of net lending, that is, new loans and line-of-credit usage minus pay-downs and write-downs, by tracking the year-over-year change in the dollar volume of outstanding business loans under $1 million as of June 30 each year from 1994 to 2011. We call these business loans under $1 million “small” loans. Of course, some loans under $1 million go to large businesses. Nonetheless, these small loans are a reasonable approximation of the volume of small business lending. Moreover, the trends we detect are comparable with those found by researchers (Rice and Rose 2010) looking at loans under $1 million made by a group of banks known to specialize in small business lending.

In the first part of the financial crisis, from June 30, 2007, to June 30, 2008, outstanding small loans from banks to businesses actually grew 3.1%. The growth was probably due at least partially to businesses drawing on lines of credit originated before the crisis struck, not from new lending. Businesses may have wanted to take advantage of these credit lines before loan commitments expired or to replace other credit sources that had been or were expected to be cut back. After that initial period, bank portfolios of small loans to businesses began to shrink. From June 30, 2008, to June 30, 2009, outstanding loans in this category dropped 2%. From June 30, 2009, to June 30, 2010, they fell an even faster 6.4%. However, from June 30, 2010 to June 30, 2011, contraction slowed to 5.5%.

We also compare trends in lending by large banks with at least $10 billion in assets with lending by small banks with less than $1 billion in assets. The larger banks are likely to have a comparative advantage in small business credit scoring, while the smaller banks are likely to have a comparative advantage in relationship lending. Call Reports distinguish loans used for business purposes that are under $1 million and secured by commercial real estate (CRE loans) from similarly sized commercial and industrial loans

that are not secured by real estate (C&I loans). We examine trends in aggregate business loan volume, that is, C&I plus CRE loans, as well as in those two categories separately. Banks do not report business loans that are collateralized by residential real estate. Such loans are incorporated into the mortgage category. All data are adjusted for mergers and acquisitions.

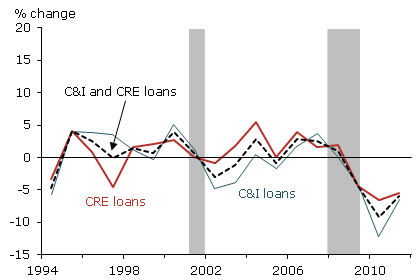

Figure 1

Changes in small business lending at large banks

Note: Year-over-year changes for loans originally valued less than $1 million made by institutions with at least $1 billion in assets, adjusted for mergers, including thrift acquisitions. Credit card banks omitted.

Source: Call Report.

The small business loan trend at large banks is similar to the trend for all banks. Aggregate small business loans at large banks shrank between June 30, 2008, and June, 30, 2009, at a steeper rate from then until June 30, 2010, and more slowly over the four quarters to June 30, 2011 (Figure 1). At those large banks, the rate of contraction moderated for small CRE loans and especially for small C&I loans.

The moderation in C&I contraction since mid-2010 is consistent with the results of the Federal Reserve’s quarterly Senior Loan Officer Opinion Survey on Bank Lending Practices, which gathers data from approximately 60 large domestic banks plus some U.S. branches and agencies of foreign banks. The July 2010 survey was the first to show an easing of standards on C&I loans to smaller businesses since late 2006 (Federal Reserve Board 2010).

But, whether positive growth in small C&I loans at large banks will soon occur and be sustained may depend on small business loan demand. The National Federation of Independent Business reports that about 25% of the small businesses it surveys cite poor sales as their main business problem. In contrast, only 3% cite financing as their main business problem, although 8% report that not all of their credit needs are satisfied (Dunkelberg and Wade 2011).

For its part, the continued sharp decrease in small CRE loans at large banks is consistent with the ongoing weakness in commercial real estate. In the office market, vacancy rates remain relatively high and rents are flat. CRE loans and residential mortgages have been the most important nonperforming asset categories at large banks (Greenlee 2010).

What about small banks?

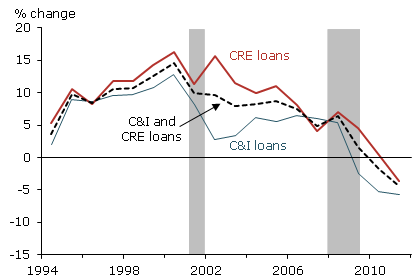

Figure 2

Changes in small business lending at small banks

Note: Year-over-year changes for loans originally valued less than $1 millon made by institutions with less than $1 billion in assets, adjusted for mergers, including thrift acquisitions. Credit card banks omitted.

Source: Call Report.

Figure 2 shows that the contraction in small C&I loan portfolios at small banks has virtually stabilized. Small C&I loan year-over-year growth rates in the 2000–2003 period bracketing the 2001 recession exhibited similar patterns at both small and large banks. This similarity indicates that certain factors tend to cause small C&I loan growth at small and large banks to move together through at least portions of the business cycle. This common pattern suggests that any distinctions in behavior between small and large bank C&I loan trends at this point in the current cycle is more a consequence of relatively minor differences in timing than of any fundamental contrasts between small bank and large bank small C&I lending that might affect how quickly each recovers after an economic contraction.

However, the 2007–2009 recession was significantly deeper and longer than the 2001 recession. It’s possible that current economic conditions will restrain recovery in small bank small C&I loans for an extended period. In this regard, loan performance may offer evidence. Banks report on the performance of all their C&I loans and do not separate out small C&I loans. Therefore, we estimate the aggregate small C&I loan nonperforming ratio at small banks by using the overall C&I loan nonperforming ratio at the subset of small banks that have at least 75% of the dollar volume of their C&I portfolio in loans under $1 million.

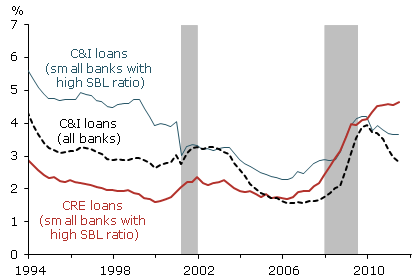

Figure 3

Delinquency rates for C&I and CRE lending

Note: Seasonally adjusted quarterly rates for CRE and C&I loans at small banks (less than $1 billion in assets) with high SBL ratios and for C&I loans at all banks. High ratio banks are determined by ratio of small business lending to total lending in given loan category. Credit card banks omitted.

Source: Call Report.

These loan performance data provide more evidence that small bank small C&I loans may be moving towards growth. Figure 3 shows that, according to our estimate, the small bank small C&I loan nonperforming ratio remains elevated after the run-up during the recession, but appears to have peaked and now be on a downward trend. The downward trend is steeper than immediately after the 2001 recession, as is the case for all C&I loans at all banks. In contrast, small bank small CRE loan portfolios show little sign yet of recovery. Figure 2 shows that the pace of lending contraction has quickened, while our nonperforming loan estimate shows a high and increasing level of delinquencies.

Conclusion

Although bank small business loan portfolios continue to shrink, hints of possible stabilization have recently appeared. For small banks, small business lending that is not backed by commercial real estate looks slightly healthier than small business lending that is secured by commercial property. Small C&I loans at larger banks are showing stronger signs of a turnaround than small C&I loans at smaller banks. But patterns observed during the 2001 recession and loan performance data suggest that smaller banks may not be far behind.

References

Berger, Allen N., Leora F. Klapper, and Gregory F. Udell. 2001. “The Ability of Banks to Lend to Informationally Opaque Small Businesses.” Journal of Banking and Finance 25(12), pp. 2127–2167.

Dunkelberg, William C., and Holly Wade. 2011. “NFIB Small Business Economic Trends.” National Federation of Independent Business, June.

Greenlee, Jon D. 2010. “Commercial Real Estate.” Testimony before the Congressional Oversight Panel Field Hearing, Atlanta, GA, January 27.

Federal Reserve Board of Governors. 2010. “The July 2010 Senior Loan Officer Opinion Survey on Bank Lending Practices.”

Mach, Traci L., and John D. Wolken. 2006. “Financial Services Used by Small Businesses: Evidence from the 2003 Survey of Small Business Finance.” Federal Reserve Bulletin, October.

Rice, Tara, and Jonathan Rose. 2010. “Small Business Lending at ‘Pure Play Banks.’” Unpublished paper, July.

Opinions expressed in FRBSF Economic Letter do not necessarily reflect the views of the management of the Federal Reserve Bank of San Francisco or of the Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System. This publication is edited by Anita Todd and Karen Barnes. Permission to reprint portions of articles or whole articles must be obtained in writing. Please send editorial comments and requests for reprint permission to research.library@sf.frb.org