Since 2001, countries around the world have been working on crafting a new global pact to liberalize trade. Despite the difficulties of completing such a multilateral agreement, it remains a worthwhile goal for two reasons. First, a global pact offers cost and efficiency benefits that can’t be achieved under the kinds of agreements among smaller groups of countries that have proliferated in recent years. Second, a global agreement presents a unique opportunity to optimize the use of the world’s resources, thereby improving well-being around the world.

International trade dropped dramatically during the recent economic crisis. Yet, despite fears that the turmoil would prompt increased barriers against imports, countries generally refrained from widespread protectionism. In 2010, trade growth bounced back, a rebound that reflects, in part, the increasing importance of bilateral and regional trade agreements. China has agreements with Chile, New Zealand, Singapore, Pakistan, and Peru, and is currently working on deals with Costa Rica, Australia, Norway, and Switzerland. Japan has pacts with Chile, Indonesia, Malaysia, Mexico, the Philippines, Singapore, Switzerland, Thailand, and Vietnam, and talks are under way with Australia, India, and Korea. Since 2001, the United States has completed negotiations with Australia, Bahrain, Chile, Colombia, Korea, Morocco, Oman, Peru, Panama, Singapore, and six countries in Central America. Furthermore, the United States, Australia, Brunei Darussalam, Chile, Malaysia, New Zealand, Peru, Singapore, and Vietnam are currently working on a regional trade agreement, the Trans-Pacific Partnership. Canada, Mexico, and Japan have expressed interest in joining. (The World Trade Organization and the Office of the U.S. Trade Representative provide information on trade agreements.) Indeed, such Preferential Trade Agreements (PTAs) have proliferated in recent years.

Still, the trade arrangement that many economists believe would deliver even more benefits—a multilateral pact involving the majority of the world’s countries—remains stubbornly elusive. This is illustrated by the lack of progress in the World Trade Organization’s (WTO) ongoing Doha Round of trade negotiations. This Economic Letter provides an update on the status of the Doha Round, explains some of the differences between bilateral and multilateral agreements, and discusses why a multilateral agreement remains a worthwhile goal, despite the proliferation of more-limited agreements.

The Doha Round of trade negotiations

Economists have long recognized the benefits of free trade. If a country buys a product from another country at a lower price than it costs to produce it at home, it will be able to use its resources more efficiently. Of course, trade has distributional consequences. Trade does not affect all groups the same way. However, for the economy as a whole, free trade can improve well-being. From an even broader perspective, global free trade provides a means of achieving the most efficient allocation of worldwide resources.

Countries around the world are currently working to reduce trade barriers on a multilateral basis. The Doha Round is the WTO’s current effort at liberalizing trade among its 153 member countries. It was kicked off in 2001 when WTO members agreed to hold talks on a range of issues, including tariffs on manufactured products and agricultural subsidies (see WTO 2001).

Since then, country representatives have met numerous times, but have failed to reach a final agreement. Indeed, in November 2010, the WTO’s director general described the Doha negotiations as “at an impasse” (see WTO 2011). This inability to successfully conclude the talks raises the question of why countries should continue to push forward under the WTO’s large multi-country umbrella, given the proliferation of bilateral and regional agreements. There are two reasons: First, important differences exist between multilateral agreements and PTAs. Second, a global agreement offers unique economic opportunities.

Multilateral agreements versus preferential trade agreements

A global trade agreement involves virtually all countries in the world, while a PTA includes a more limited set of them. There are important differences between these two categories. For example, countries involved in PTAs may not take into account the effect of their pacts on trade with third-party nations that are not part of the agreements. In addition, a multiplicity of PTAs could create high levels of complexity in trade rules.

Trade creation versus trade diversion

Jacob Viner first explained how trade with countries not party to an agreement could affect the countries that are part of an agreement (see Viner 1950). He argued that trade agreements have benefits because the imports they promote may replace less-efficient domestic production, an effect he called “trade creation.” However, by giving preferential access to one particular trading partner at the expense of others, an importing nation may be diverting its purchases from a more-efficient, lower-cost country that is not part of the agreement. Thus, the importing country pays a higher price for products under the trade agreement because it has shifted to a higher-cost source. Viner termed this phenomenon “trade diversion.” The ultimate impact of a PTA involving fewer than all countries in the world depends on the trade-off between trade creation and trade diversion.

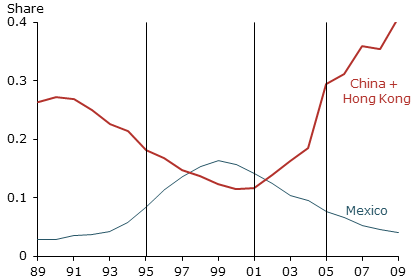

Figure 1

Composition of U.S. apparel imports

Source: U.S. Office of Textiles and Apparel.

To illustrate how trade diversion could work, consider U.S. trade in apparel. The United States has historically placed a variety of restraints on clothing imports. Figure 1 shows changes in U.S. apparel imports between 1989 and 2009. The figure highlights three important dates in the history of U.S. clothing import policy. At the end of 1994, NAFTA came into effect, reducing barriers on imports from Mexico. At the end of 2001, China joined the WTO, which reduced some constraints on U.S. apparel imports from that country. And, at the beginning of 2005, the Multi-Fiber Agreement (MFA), a system of quotas on worldwide U.S. apparel imports, officially ended. When it expired, some tariffs still restricted U.S. apparel imports, but the United States moved in the direction of unconstrained trade.

As Figure 1 shows, each of these events changed the preferences the United States extended to its trading partners and was accompanied by shifts in sources of U.S. imports. After NAFTA’s enactment, Mexico’s share increased substantially, while China’s share fell. Of course, other factors, such as Mexico’s geographical proximity to the United States, played a role. But changes in trade barriers were instrumental in this shift (see Evans and Harrigan 2005). Once the United States began to relax restrictions on Chinese imports, Mexico no longer enjoyed such preferential access to the U.S. market. Its share fell substantially, while China’s rose. Most markedly, when MFA apparel import quotas were completely eliminated at the beginning of 2005, China’s share increased dramatically. It went from 19% in 2004 to 41% in 2009, while Mexico’s fell from 10% to 4%. One recent study on NAFTA’s overall effects concluded that the agreement did indeed create trade diversion for the United States (see Romalis 2007).

The “spaghetti bowl” syndrome

Figure 2

“Spaghetti bowl” of trade agreements

A second way that a multilateral agreement differs from a multiplicity of PTAs involves the potential complexity of trade rules created by a series of arrangements between different pairs of countries (see Bhagwati 1995). In Figure 2, each of the colored shapes represents a country, while each of the lines represents a trade agreement between a pair of countries. This type of proliferation of agreements has been termed a “spaghetti bowl” because there are so many overlapping bilateral arrangements among nations. Such a complex mesh of relationships could have the unintended effects of raising the cost of trade and distorting production patterns across countries. These consequences may emerge from two aspects of a plethora of trade agreements: rules of origin and tariff rates.

Rules of origin set out standards determining where a particular product originates. They specify that, in order for a product to be deemed to originate from a certain country, a meaningful portion of that product’s value must come from that country. Rules of origin are put in place to eliminate cheating, whereby one country imports a product from a non-partner country and then re-exports it to the free-trade partner. Satisfying rules-of-origin requirements has become increasingly complex, since production processes now stretch across multiple countries. When an assembling country sources inputs from a number of other countries and then exports the finished product to another final market, it becomes difficult to determine exactly where the product originates. Since each PTA has its own rules of origin for particular parties to the agreement, meeting those requirements may become quite complicated.

Different trade agreements also lead to separate tariff rates on imports from different countries. For example, U.S. imports of a certain kind of men’s trousers from most countries face a duty of $0.61 per kilogram plus 15.8% of the product’s value. However, if the trousers are imported from Bahrain, Canada, Chile, Israel, Jordan, Mexico, Peru, or Singapore, no duty is imposed. Trousers from Australia incur an 8% tariff; from Morocco $0.62 per kilogram plus 1.6%; and from Oman $0.488 per kilogram plus 12.6%. For non-WTO member countries, a $0.772 per kilogram plus 54.5% tariff is imposed. (See http://www.usitc.gov/publications/docs/tata/hts/bychapter/1002c61.pdf. These rates are for HS number 6103.41.10.)

Rules of origin and the profusion of tariff rates increase the costs of trade, both for businesses involved in cross-border commerce and governments enforcing trade rules. Furthermore, they may distort production decisions as businesses navigate the web of rules and rates to minimize transaction costs.

Looking to the future

The WTO’s effort to work out a global trade agreement is justified not only by the costs and distortions that PTAs impose, but also because such a pact offers unique economic opportunities over and above what is available via more limited agreements.

As noted earlier, if a country buys a product from another country at a lower price than it can produce it at home, it will be able to use its own resources more efficiently. Multilateral free trade provides a great opportunity to optimize the use of the world’s resources, thereby improving well-being around the world. Broadly speaking, if all countries were to eliminate tariffs, then resources could be used in all countries in the most advantageous way possible. At present, only the WTO’s Doha Round offers the potential to achieve that goal.

As a final point, the worldwide proliferation of PTAs raises the question of whether they help or hinder progress on a multilateral deal. Economists actively debate this point. On one side are those such as Jagdish Bhagwati who argue that PTAs create stumbling blocks to world trade agreements. PTAs may be hindrances for a number of reasons. Most countries lack the administrative resources to pursue both regional and global negotiations. And they may hold back on reducing tariffs in multilateral negotiations so that reductions can be offered as bargaining chips in bilateral or regional trade talks.

Economists such as Richard Baldwin take the opposing view, arguing that PTAs are in fact building blocks.” Countries may feel pressured to participate in a broad agreement because they could lose out if their PTA partners shift trade toward countries involved in global negotiations. PTAs may also boost support for a broader free trade agreement when businesses maneuvering through a “spaghetti bowl” of rules and requirements recognize the benefits of a unified set of rules. Baldwin cites the example of the 1997 Information Technology Agreement. Because information technology production processes stretch across multiple countries, the benefits of a global agreement became apparent to the signatories.

Conclusion

Despite the difficulties involved in reaching an agreement involving so many countries, the WTO’s Doha Round deserves continued focus and effort. While countries have completed many bilateral and regional agreements, a broad multilateral agreement offers the possibility of additional, unique benefits.

References

Baldwin, Richard. 2006. “Multilateralising Regionalism: Spaghetti Bowls as Building Blocs on the Path to Global Free Trade.” The World Economy 29(11), pp. 1451–1518.

Bhagwati, Jagdish. 1995. “U.S. Trade Policy: The Infatuation with FTAs.” Columbia University Discussion Paper Series 726.

Bhagwati, Jagdish. 2008. Termites in the Trading System: How Preferential Agreements Undermine Free Trade. New York: Oxford University Press.

Evans, Carolyn L., and James Harrigan. 2005. “Distance, Time, and Specialization: Lean Retailing in General Equilibrium.” American Economic Review 95(1), pp. 292–313.

Romalis, John. 2007. “NAFTA’s and CUSFTA’s Impact on International Trade.” Review of Economics and Statistics 89(3), pp. 416–435.

Viner, Jacob. 1950. The Customs Union Issue. New York: Carnegie Endowment for International Peace.

World Trade Organization. 2001. “Doha WTO Ministerial 2001: Ministerial Declaration,” WT/MIN(01)/DEC/1, November 20.

World Trade Organization. 2011. “Report by the Director General,” WT/MIN(11)/5, November 18.

Opinions expressed in FRBSF Economic Letter do not necessarily reflect the views of the management of the Federal Reserve Bank of San Francisco or of the Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System. This publication is edited by Anita Todd and Karen Barnes. Permission to reprint portions of articles or whole articles must be obtained in writing. Please send editorial comments and requests for reprint permission to research.library@sf.frb.org