Part-time work spiked during the recent recession and has stayed stubbornly high, raising concerns that elevated part-time employment represents a “new normal” in the labor market. However, recent movements and current levels of part-time work are largely within historical norms, despite increases for selected demographic groups, such as prime-age workers with a high-school degree or less. In that respect, the continued high incidence of part-time work likely reflects a slow labor market recovery and does not portend permanent changes in the proportion of part-time jobs.

The share of employed individuals working part time rose from about 17% in 2007 just before the recession to nearly 20% in 2009 and stayed near that level through mid-2013. Some observers worry that this stubbornly high prevalence of part-time work may be one feature of an unfavorable “new normal” in the labor market. However, understanding the current high incidence of part-time employment and what it means for the labor market requires taking a longer view than the most recent business cycle. In this Economic Letter, we examine part-time employment since 1976 and earlier, the period for which detailed data on part-time workers are available. The incidence of part-time work is little changed relative to the recession of the early 1980s once changes in survey measurement are taken into account. Nonetheless, increases for various demographic groups underlie this overall stability, a trend that has accelerated because of a recession-induced shift towards involuntary part-time work. Still, the elevated level of involuntary part-time work is likely to fall as the labor market recovery continues.

Trends in part-time work

The U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS) generally defines part-time workers as those who typically work fewer than 35 hours per week, including all the jobs they hold. Data on part-time employment are available from the Current Population Survey (CPS), the monthly survey of 60,000 households that is the source for the government’s official unemployment rate and related labor force measures. The BLS publishes several monthly series on part-time employment. We focus on the most commonly cited BLS part-time series definitions, from tables A-9 and A-8 of the BLS monthly Employment Situation Release. For consistency across our analyses, we calculated these series from the monthly CPS data files for the period from 1976 through June 2013, essentially replicating the published BLS series. Our series are generally displayed on an annual rather than monthly basis. The value for 2013 is based on the first six months of the year.

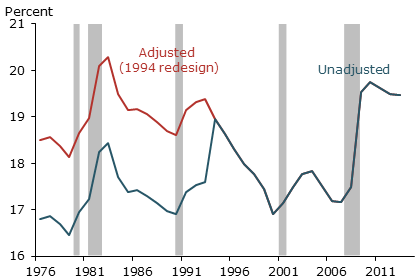

Figure 1

Part-time employment as a share of total employment

Source: CPS and authors’ calculations.

Note: Gray bars show NBER recession dates.

Figure 1 shows the annual average percentage of employed individuals working part time. The divided lines in the figure reflect the impact of a major redesign of the CPS survey in 1994. The redesigned survey posed questions about hours worked based on usual weekly hours, which allowed some people working 35 or more hours in the week of the survey to be classified as part time. As a result, measured part-time work increased abruptly. In assessing changes that span the pre- and post-1994 redesign period, it is important to adjust for this discontinuity. BLS staff members (Polivka and Miller 1998) have provided adjustment factors to account for the impact of the survey redesign. Because BLS adjustment factors are not available for the entire range of series that we analyze, we estimated our own adjustment factors based on a statistical analysis that incorporates business cycle and time components. This method yielded adjustment factors nearly identical to those of Polivka and Miller.

Figure 1 shows that part-time work typically increases in recessions, which reflects the cyclical reduction in labor demand that reduces hours worked along with increasing the unemployment rate. The increase in part-time work during the most recent recession was especially large, which is not surprising given the size of the cyclical downturn. However, the current level of part-time work is not high by historical standards based on comparison with the adjusted series for the pre-1994 period displayed in the figure. In particular, on a consistent basis, the part-time employment share peaked at 20.3% in 1983, slightly above the recent peak of 19.7% in 2010. By this standard, the level of part-time work in recent years is not unprecedented, although its persistence during the ongoing recovery is unusual.

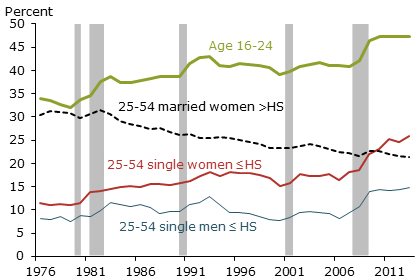

Figure 2

Part-time employment for selected groups

Source: CPS and authors’ calculations.

Note: Percent of total employment for each group. Gray bars show NBER

recession dates.

Demographic factors

The simple long-term comparison made above ignores relevant changes in the structure of the workforce. The most important of these is the change in the age structure, most notably the declining share of young workers. Various factors, such as financial dependence on their parents, school enrollment, relatively low skills, and, more generally, weak labor force attachment, have made young workers much more likely to work part time than older workers. Figure 2 shows the incidence of part-time work for selected demographic groups, adjusted for the 1994 survey redesign. Workers age 16 to 24 are much more likely than prime-age workers age 25 to 54 to work part time. Moreover, the prevalence of part-time work for the 16–24 age group has increased substantially over time. However, this has been more than offset by the shrinking proportion of this group in the workforce. It dropped from about 23% of employed individuals in the late 1970s to just over 12% in recent years, putting substantial downward pressure on the overall prevalence of part-time work.

The downward pressure on part-time work caused by the declining employment share of young workers was offset by an increase in the prevalence of part-time work among other groups, including prime-age unmarried male and female workers age 25 to 54 with a high school degree or less, as shown in Figure 2. By contrast, part-time work has declined for married women with more than a high school education. Overall, it appears that the decline in the pool of teenagers and married women who prefer to work part time was offset by increases in the proportion of part-time workers among other demographic groups who in the past were less likely to work fewer than 35 hours per week. The increase among these groups was especially large in the recent recession and its aftermath.

Reasons for working part time

Among part-time workers, the BLS distinguishes two main groups. The first consists of individuals working part time for economic reasons. They would prefer full-time work and are typically regarded as involuntary part-time workers. The primary economic reasons for working part time are business slack or unfavorable conditions that prompt employers to cut back hours, or the inability of a worker to find full-time employment. The second group of part-time workers consists of individuals who cite noneconomic reasons and are typically regarded as voluntary part-time workers in the sense that their status reflects individual preferences or needs rather than employer requirements. Noneconomic reasons primarily include medical conditions, child-care needs, other family or personal obligations, school or training, and retirement.

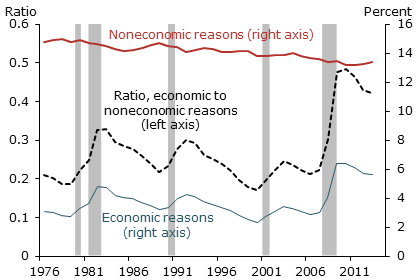

Figure 3

Part-time employment by reason

Source: CPS and authors’ calculations.

Note: Percent is share of total employment. Gray bars show NBER

recession dates.

Figure 3 shows the prevalence of the two categories of part-time work and their ratio, adjusted for the 1994 survey redesign. Most part-time work is for noneconomic reasons. However, the incidence of this category has been trending down over time. By contrast, part-time work for economic reasons has a substantial cyclical component, rising in recessions and falling in recoveries. The increase in the most recent recession was especially large.

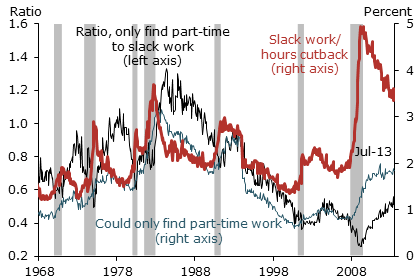

Figure 4

Part-time employment for economic reasons

Source: BLS/Haver Analytics and authors’ calculations.

Note: Seasonally adjusted data. Percent is share of total employment.

Gray bars show NBER recession dates.

Figure 3 shows that the prevalence of involuntary part-time employment has remained high. Further insight can be gleaned from a breakdown of the economic-reasons group into its primary subcomponents: slack work that causes hours cutbacks and an inability to find a full-time job. Figure 4 shows the prevalence of these two subcomponents and their ratio. The slack work subcomponent is highly cyclical, with increases and declines typically tied closely to recession dates (BLS 2008). Movements in the inability to find full-time work subcomponent tend to lag behind the slack work component. In 2012 and 2013 through July, this component continued to rise slightly as the slack work subcomponent fell. This is unsurprising given that the U.S. labor market has recovered only about three-fourths of the jobs lost during the recession and its aftermath, which leaves finding a full-time job still challenging for many workers. However, the ratio of this subcomponent to the hours cutback subcomponent remains low in historical terms, suggesting that general labor market slack remains the key factor keeping part-time employment high.

Discussion

We have shown that part-time work is not unusually high relative to levels observed in the past, most notably in the aftermath of the early 1980s recession. However, while the availability of young workers age 16 to 24 in the labor force is declining, the prevalence of part-time work has increased in that group. In addition, part-time work has been rising among selected groups of prime-age workers age 25 to 54, primarily those with limited education. Moreover, involuntary part-time work, that is, part-time work for economic reasons, remains high. These factors have fueled speculation that elevated rates of part-time work may be here to stay. However, it is more probable that the continued high incidence of individuals working part time for economic reasons reflects a slow recovery of the jobs lost during the recession rather than permanent changes in the proportion of part-time jobs.

An alternative interpretation of the persistent high level of involuntary part-time work due to an inability to find full-time work is that it reflects employer anticipation of the 30-hour cutoff for mandatory employee health benefits under the Affordable Care Act (ACA) of 2010. Media stories have suggested that some employers are only hiring part-time workers to minimize the cost of expanded health coverage. This phenomenon will probably continue, although perhaps at a slower pace due to the recently announced delay in implementation of the employer mandate to 2015.

In any event, both the impact of the law so far and the ultimate effect are likely to be small. Before the law was passed, most large employers already faced IRS rules that prevented them from denying available health benefits to full-time workers. These rules gave employers an incentive to create part-time jobs to avoid rising health benefit costs. Moreover, recent research suggests that the ultimate increase in the incidence of part-time work when the ACA provisions are fully implemented is likely to be small, on the order of a 1 to 2 percentage point increase or less (Graham-Squire and Jacobs 2013). This is consistent with the example of Hawaii, where part-time work increased only slightly in the two decades following enforcement of the state’s employer health-care mandate (Buchmueller, DiNardo, and Valletta 2011).

References

Buchmueller, Thomas C., John DiNardo, and Robert G. Valletta. 2011. “The Effect of an Employer Health Insurance Mandate on Health Insurance Coverage and the Demand for Labor: Evidence from Hawaii.” American Economic Journal: Economic Policy 3 (November), pp. 25–51.

Graham-Squire, Dave, and Ken Jacobs. 2013. “Which Workers Are Most at Risk of Reduced Hours under the Affordable Care Act?” UC Berkeley Labor Center Data Brief, February.

Polivka, Anne, and Stephen Miller. 1998. “The CPS After the Redesign: Refocusing the Economic Lens.” In Labor Statistics Measurement Issues, eds. John Haltiwanger, Marilyn Manser, and Robert Topel. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, pp. 249–289.

U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics. 2008. “Involuntary Part-Time Work on the Rise.” Issues in Labor Statistics 08-08 (December).

Opinions expressed in FRBSF Economic Letter do not necessarily reflect the views of the management of the Federal Reserve Bank of San Francisco or of the Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System. This publication is edited by Anita Todd and Karen Barnes. Permission to reprint portions of articles or whole articles must be obtained in writing. Please send editorial comments and requests for reprint permission to research.library@sf.frb.org