Over the past two years, both monetary and fiscal policy projections have been based on the view that declines in the long-run potential growth rate of the economy will in turn push down interest rates. In contrast, examination of private-sector professional forecasts and historical data provides little evidence of such a linkage. This suggests a greater risk that future interest rates may be higher than expected.

The aging of the labor force, weak productivity growth, and possible long-run supply-side damage from the Great

Recession have all suggested recently that the potential growth rate of the U.S. economy may be lower in the years

ahead. According to standard economic theory, such slower growth would push down the level of the natural rate of

interest. This natural rate, also called the neutral or equilibrium real interest rate, is the risk-free short-term

interest rate adjusted for inflation that would prevail in normal times with full employment (Williams 2003).

Moreover, a decline in the natural rate of interest would tend to lower every other real and nominal interest rate in

the economy. Therefore, understanding the linkage between economic growth and the natural rate is crucial for

forecasting all types of interest rates. Indeed, this linkage has been at the center of recent fiscal and

monetary policy forecasts. The Congressional Budget Office (CBO 2014) noted that its lower projections of U.S.

Treasury yields and the federal government’s future debt servicing costs partly reflected reductions in its forecast

for potential output. In addition, earlier this year, some Federal Open Market Committee (FOMC) participants appeared

to reduce their estimates of the natural rate of interest because of an expectation of slower growth ahead for

potential output.

This Economic Letter examines the linkage between growth and interest rates as embodied in recent

projections by FOMC participants, the CBO, and private-sector forecasters. Although forecasts of potential growth or

the natural rate are rarely reported, we can construct reasonable proxies from long-run forecasts of GDP growth, the

short-term interest rate, and inflation. In essence, the long-run nature of these forecasts strips out cyclical

variation and reveals the fundamental secular trends that underlie the concepts of potential growth and the natural

rate of interest.

Although in the CBO and FOMC policy projections long-run forecasts of growth and the real interest rate have fallen

together, private-sector forecasters do not anticipate a similar dual drop. In particular, the recent downward

revisions in private-sector expectations for long-run growth have been associated with no change in their long-run

projections of the real short-term interest rate. If the private-sector forecasters are correct, this would raise a

concern that the CBO and FOMC may have overestimated the effects of slower potential growth toward reducing interest

rates, which may introduce some upside risk to CBO and FOMC interest rate projections.

FOMC and CBO projections of growth and interest rates

In standard economic theory, the natural interest rate—that is, the short-term real interest rate at which the

economy would stay at full employment—is related positively to the growth rate of potential output. Higher potential

growth can affect the real interest rate via two key channels. First, it increases the returns on investment and thus

leads to higher investment demand. Second, because higher growth boosts future earnings, it leads forward-looking

households to consume more and save less. The combination of higher investment and lower savings raises the real

interest rate. As a result, higher potential growth would be associated with a higher natural rate (Laubach and

Williams 2003). Of course, this simple theory is not definitive, and in the real world, other factors may obscure or

overwhelm this relationship, including those highlighted in the recent debate about secular stagnation (Summers 2014).

Most importantly perhaps, in an open economy with international financial flows, the real interest rate is determined

by the interaction of growth, saving, and investment at a global level—rather than by developments in any

single country.

Because we do not directly observe the natural rate of interest or potential trend growth, we construct proxies from

long-run forecasts of real GDP growth and short-term real interest rates. Since the impact of cyclical shocks

diminishes over time, long-run projections should capture forecasters’ views of secular influences in the economy,

which are the factors that affect potential growth and the natural rate.

We first examine long-run policy projections of real GDP growth and the short-term real interest rate from the FOMC

and the CBO. FOMC forecasts are reported four times per year in the FOMC’s Summary of Economic Projections (SEP).

Long-run real GDP growth forecasts are available since 2009. Long-run forecasts of the equilibrium real interest rate

can be constructed since 2012 using long-run forecasts of the nominal federal funds rate and of inflation in the price

index for personal consumption expenditures. We use the midpoint of the forecasts’ central tendency, which excludes

the three highest and three lowest projections. The CBO’s long-run forecasts are available since 1996. We use the

average of five- to ten-year-ahead forecasts. We calculate the real interest rate forecast using projections of the

three-month Treasury bill rate and of inflation in the consumer price index (CPI). Based on historical differences

among the data series, we subtract 0.3 percentage point from the CPI inflation forecasts and add 0.2 percentage point

to the Treasury bill rate forecasts to make them broadly comparable to the FOMC projections.

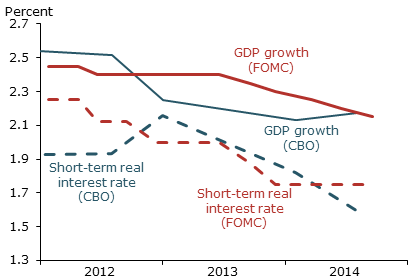

Figure 1

Long-run FOMC and CBO projections

Figure 1 depicts the evolution of the FOMC and the CBO long-run forecasts for real GDP growth and the short-term real

interest rate. Since the beginning of 2012, FOMC participants have lowered their projections of the short-term rate

from 2.3% to 1.7%, and one likely important factor behind this decline was the FOMC participants’ more pessimistic

outlook for long-run GDP growth, reflected in Figure 1. The June 2014 FOMC minutes described the connection: “Compared

with March, some participants revised down their estimates of the longer-run federal funds rate, with a lower

assessment of the longer-run level of potential output growth cited as a contributing factor for the majority of those

revisions” (Board of Governors 2014).

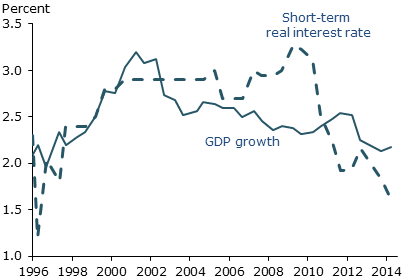

Figure 2

Long-run CBO projections

Figure 1 also shows that the CBO lowered its estimate of the short-term real interest rate by roughly 0.4 percentage

point since the beginning of 2012. Echoing the views of FOMC participants, the latest report on the long-term budget

outlook from the CBO (2014) emphasized that a key factor behind the declining real rate was the decline in potential

growth. This link between potential growth and the natural real interest rate is also evident in the CBO’s projections

since the mid-1990s, shown in Figure 2. The two series have a fairly close correlation of 0.5.

Evidence from private-sector forecasts and historical data

Are the views of FOMC participants and the CBO about the linkage between long-run growth and interest rates shared by

private-sector forecasters? Since 1986, the Blue Chip Economic Indicators has reported long-run forecasts from

business economists for growth and interest rates. We use the average five- to ten-year-ahead consensus forecasts for

real GDP growth and for the short-term real interest rate. We base the latter on projections of the federal funds rate

and CPI inflation adjusted by 0.3 percentage point.

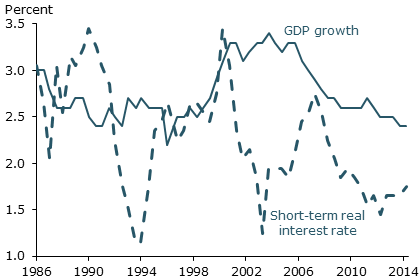

Figure 3

Long-run Blue Chip projections

Figure 3 shows the movements in the Blue Chip forecasts for real GDP growth and the short-term real interest rate.

Like the FOMC and CBO, private forecasters have also lowered their projections of long-run growth since 2012. However,

despite this weaker growth outlook, the Blue Chip long-run estimates of the short-term real interest rate have

actually edged up during this period. Furthermore, this recent episode is not unusual. Over the past three decades, it

appears that private forecasters have incorporated essentially no link between potential growth and the natural rate

of interest: The two data series have a zero correlation.

This evidence is surprising given the predictions of standard economic theory, but it is in line with some other

research findings. For instance, Goldman Sachs (2014) recently examined the effect of real per-capita GDP growth on

short-term real interest rates in 20 countries since the early 1800s. The report found no statistically significant

relationship between these two variables. Similarly, Carroll and Summers (1991) and Bosworth (2014) found at best a

weak positive relationship between growth and short-term real interest rates using data for a number of countries.

A strong positive link between higher growth and higher real interest rates depends in part on a decline in the

saving rate, arising from household assumptions about longer-term income. However, much research has instead found

that higher growth is associated with a higher saving rate (for example, International Monetary Fund 2014). In this

case, although higher growth would raise investment demand and put upward pressure on real interest rates, this effect

would be mitigated by a rise in the saving rate.

The Blue Chip results could be interpreted in three ways. First, it’s possible that the private forecasters are

naively ignoring an important growth and interest rate connection that is obvious in policy projections.

Alternatively, it is possible that the Blue Chip forecasters have a more subtle understanding of the many factors

other than growth that influence investment and saving in a way that masks a positive connection between potential

growth and the equilibrium real interest rate. Finally, the Blue Chip forecasters may correctly recognize that there

is no significant relationship between potential growth and the equilibrium real funds rate. If either the second or

third of these interpretations were true, it would imply that many FOMC participants and the CBO may have

overemphasized the effect that weaker potential growth has on damping future interest rates.

Conclusions and policy implications

In this Letter, we document a range of views about the link between potential growth and the natural

interest rate. In particular, while the CBO and many FOMC participants expect weaker long-run growth to translate into

lower interest rates, private-sector forecasts do not seem to share this view. Thus, future downward pressure on

interest rates may be more muted than indicated by current monetary and fiscal policy projections, which would

translate into an upside risk to these longer-term interest rate forecasts.

Sylvain Leduc is a vice president in the Economic Research

Department of the Federal Reserve Bank of San Francisco.

Glenn D. Rudebusch is director of economic research and executive vice president in the Economic Research Department

of the Federal Reserve Bank of San Francisco.

References

Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System. 2014. “Minutes of the Federal Open

Market Committee,” June 17–18.

Bosworth, Barry P. 2014. “Interest Rates and Economic Growth: Are They Related?” Brookings Institution Working paper.

Carroll, Christopher D., and Lawrence H. Summers. 1991. “Consumption Growth Parallels Income Growth: Some New

Evidence.” Chapter in National Saving and Economic Performance, eds. B. Douglas Bernheim, and John B. Shoven.

Chicago: Chicago University Press, pp. 305–348.

Congressional Budget Office. 2014. “An Update to the Budget and Economic

Outlook: 2014 to 2024.” August.

Goldman Sachs Global Macro Research. 2014. “Some Long-Term Evidence on Short-Term Rates.” U.S. Economics

Analyst 14(25, June 20).

International Monetary Fund. 2014. “Perspectives on Global Real Interest Rates.” World Economic Outlook,

Chapter 3.

Laubach, Thomas, and John C. Williams. 2003. “Measuring the Natural Rate of Interest.” Review of Economics and

Statistics 85(4, November), pp. 1,063–1,070.

Summers, Lawrence H. 2014. “U.S. Economic Prospects: Secular Stagnation, Hysteresis, and the Zero Lower Bound.”

Business Economics 49(2), pp. 65–73.

Williams, John C. 2003. “The Natural

Rate of Interest.” FRBSF Economic Letter 2003-32 (October 31).

Opinions expressed in FRBSF Economic Letter do not necessarily reflect the views of the management of the Federal Reserve Bank of San Francisco or of the Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System. This publication is edited by Anita Todd and Karen Barnes. Permission to reprint portions of articles or whole articles must be obtained in writing. Please send editorial comments and requests for reprint permission to research.library@sf.frb.org