Place-based policies such as enterprise zones offer economic incentives to firms to create jobs in economically challenged areas. Evidence on the effectiveness of enterprise zones is mixed. There is no clear indication that they successfully create jobs. However, positive effects are evident for other policies, including discretionary subsidies that target specific firms, infrastructure spending that targets specific areas, and investment in higher education and university research.

Place-based policies refer to government efforts to enhance the economic performance of specific areas within their jurisdiction. Most commonly, place-based policies target underperforming areas, such as deteriorating downtown business districts in the United States or disadvantaged areas in European Union countries. But they can also be designed to improve the economic performance of areas that are already doing well, for example by encouraging further development of an existing cluster of businesses concentrated in a particular industry.

Do these place-based policies work? This question is difficult to answer because finding similar areas that were not targeted for assistance to use for an appropriate comparison is a challenge. Moreover, the local emphasis of these policies implies that we have to account for the possibility that workers and businesses may move in response to policy incentives. This mobility can lead to benefits going to those who were not originally targeted. A further concern is that, even if a place-based policy benefits one area, it can reduce economic activity in another area, which raises the question of whether these policies increase overall economic activity. This Economic Letter distills some key lessons from research on place-based policies drawn from an extensive review of recent research (Neumark and Simpson, forthcoming). Compared with Wilson (2015), we focus on the measured impact of specific types of policies at the local level rather than broader considerations regarding the design of state and local tax incentives for businesses.

Types of place-based policies

The most prominent place-based policy in the United States is federal and state urban enterprise zones. For example, federal Empowerment Zones consist of relatively poor, high-unemployment Census tracts. They offer businesses tax credits of up to $3,000 per worker for hiring zone residents and (in the original zones) block grants of up to $100 million to be used for business assistance, infrastructure investment, and training programs. Benefits vary across state programs, but many also emphasize hiring credits.

An early place-based policy was the Tennessee Valley Authority (TVA) begun in 1933. This federal initiative sought to modernize the economy of the Tennessee Valley region (Kline and Moretti 2014) through large public infrastructure spending with an emphasis on hydroelectric dams to generate power sold locally to encourage manufacturing.

In the European Union (EU), Structural Funds support economic development in disadvantaged areas. European governments can also offer subsidies to businesses in these areas, in the form of discretionary grants for new capital investment with the aim of creating or maintaining jobs. Other European place-based policies directly aimed at firms include incentives to support industrial clusters. Sweden has also tried to use the location of new universities to increase local labor force skills and exploit university research to attract private-sector activity to an area.

Why use place-based policies

Place-based policies target areas, rather than people or firms. There are a number of rationales for place-based policies based on promoting economic efficiency. A core concept in urban economics is the idea of agglomeration economies, which posits that locations that are denser in jobs and people are more efficient and productive, perhaps because of learning shared among people, called “knowledge spillovers,” or because there are better matches between workers and firms. The flip side is that firms and workers relocating to one area may reduce agglomeration economies in the areas from which they move. Because of this, a rationale for place-based policies based on agglomeration requires that the overall gains outweigh the losses, which can be hard to establish.

One argument about agglomeration is that bringing high-skilled workers to an area generates benefits for the productivity of other workers, although the trade-off across areas remains. Another argument is that there are agglomeration effects within industries, so that promoting industrial clusters can be beneficial.

There are also distributional arguments for place-based policies. Policymakers might want to create jobs in a poor urban area even if this entails fewer jobs in other locations, especially if getting poor people to move to other areas to find jobs is difficult or ineffective (as suggested in Ludwig et al. 2013). But mobility responses can complicate matters. For example, if workers move into an area after a hiring credit increases wages and employment, house prices and rents could also rise, generating gains for property owners who are not the intended beneficiaries. Moreover, some of the job market benefits go to those who moved in, while original residents may be pushed out by higher rents.

Evidence on the effects of enterprise zones

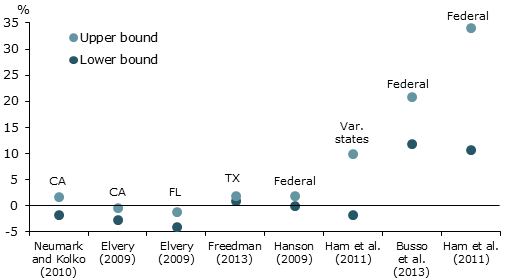

These considerations imply that assessing evidence on place-based policies such as enterprise zones requires looking at the many margins on which outcomes can change. To estimate the effects of enterprise zones, researchers try to construct valid comparison areas where benefits do not apply, such as similar areas close to the zones or areas that met the criteria for designation as enterprise zones but were not selected. While the findings are mixed, evidence generally does not support the conclusion that enterprise zones create jobs. Figure 1 displays the range of estimates from eight recent studies of enterprise zone effects on the percent change in employment. In most cases the different estimates come from alternative statistical approaches; an exception is the Ham et al. (2011) state-level estimates, where the range is over different states. The first five studies in the figure find no evidence of employment effects. However, the last three provide evidence of large positive effects. The Ham et al. (2011) state-level estimates are potentially suspect; their estimates suggest some of the largest employment effects occur in states with little to no hiring credits, while California’s large hiring credit had among the smallest effects.

Figure 1

Range of enterprize zone effects on employment

In assessing federal programs, Busso et al. (2013) find large positive effects of federal Empowerment Zones. Although this finding differs from much of the literature, it is possible that it reflects a unique feature of these zones—specifically, large block grants. The Ham et al. (2011) estimates for federal programs are even larger, yet this study finds some effects on other outcomes, particularly in reducing poverty, that are larger for federal Enterprise Communities, which had more restricted hiring credits and did not receive major block grants. In our view this casts doubt on the study’s findings, and we omit it from some of the discussion below. Finally, the Hanson (2009) study also examines federal Empowerment Zones and finds little evidence of an employment effect.

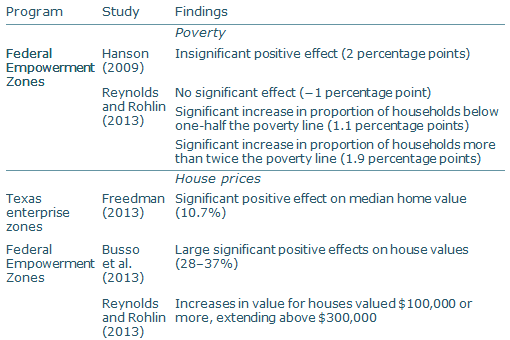

Even if there is some evidence that federal enterprise zones create jobs, assessments of their effectiveness must be tempered by other research findings summarized in Table 1. First, even though some research on federal Empowerment Zones finds some evidence of positive employment effects, other research fails to find evidence of reduced poverty, and points to some increases in the share of households falling below other low income thresholds. Second, there is consistent evidence of housing price increases, implying that benefits are received by unintended recipients. Other results not included in the table sometimes point to negative spillover effects on nearby areas, suggesting that enterprise zones largely rearrange the location of jobs rather than creating more of them.

Table 1

Effects of enterprize zones on poverty and house prices

Our overall view of the evidence is that state enterprise zone programs have generally not been effective at creating jobs. The jury is still out on federal programs—Empowerment Zones in particular—and we need more research to understand what features of enterprise zones help spur job creation. Moreover, even if there is job creation, it is hard to make the case that enterprise zones have furthered distributional goals of reducing poverty in the zones, and it is likely that they have generated benefits for real estate owners, who are not the intended beneficiaries.

Evidence on other place-based policies

Neumark and Simpson (forthcoming) also compare studies of discretionary subsidies targeted to businesses in underperforming areas in European countries and location-based subsidies in the United States. These studies suggest positive effects on investment, employment, and productivity spillovers. The discretionary nature of these subsidies may help explain their success, because applications for subsidies pass through an initial scrutiny, and targeted outcomes can be monitored so that the payment of the subsidy is contingent on job or investment targets being met.

Evidence also suggests that higher-education institutions generate productivity spillovers that may be highly localized. Not surprisingly, these benefits are specific to industries with technological links to university research and that employ many university graduates. Some evidence finds that university research facilities attract high-tech, innovative firms to an area, which can help form industry clusters that may deliver longer-term benefits from agglomeration. Much of the evidence is from long-established universities, although research from Sweden points more directly to new universities increasing local labor productivity with benefits that do not appear to create negative effects in other regions.

Finally, analysis of the TVA program and EU Structural Funds indicates that infrastructure investment can deliver productivity growth in targeted regions, and can act as a redistributive tool across areas, although questions remain about how long these effects last.

Some promise, some pitfalls, and many unknowns

The extensive research on place-based policies indicates that some types of well-designed policies can be effective, while other policies do not appear to be. Policies that subsidize businesses based solely on their location are hard to defend based on the research record. Place-based policies used in a more discretionary fashion seem to work better, perhaps because policymakers can target subsidies where they will do the most good and also hold recipients accountable. And place-based policies that generate public goods such as infrastructure and knowledge appear beneficial, perhaps because these goods are underprovided by the private sector.

But even among the more effective policies, exactly what makes them work is unclear. Past research can provide some guidance, but the lack of consistent evidence means that any such policies need to be continually monitored and evaluated to see whether they actually deliver their intended benefits.

David Neumark is Chancellor’s Professor of Economics and Director of the Center for Economics & Public Policy at the University of California, Irvine, and a visiting scholar at the Federal Reserve Bank of San Francisco.

Helen Simpson is Reader in Economics at the Centre for Market and Public Organisation, University of Bristol.

References

Busso, Matias, Jesse Gregory, and Patrick Kline. 2013. “Assessing the Incidence and Efficiency of a Prominent Place Based Policy.” American Economic Review 103, pp. 897–947.

Elvery, Joel. 2009. “The Impact of Enterprise Zones on Residential Employment: An Evaluation of the Enterprise Zone Programs of California and Florida.” Economic Development Quarterly 23, pp. 44–59.

Freedman, Matthew. 2013. “Targeted Business Incentives and Local Labor Markets.” Journal of Human Resources 48, pp. 311–344.

Ham, John, Charles Swenson, Ayse Imrohoroglu, and Heonjae Song. 2011. “Government Programs Can Improve Local Labor Markets: Evidence from State Enterprise Zones, Federal Empowerment Zones, and Federal Enterprise Communities.” Journal of Public Economics 95, pp. 779–797.

Hanson, Andrew. 2009. “Local Employment, Poverty, and Property Value Effects of Geographically-Targeted Tax Incentives: An Instrumental Variables Approach.” Regional Science and Urban Economics 39, pp. 721–731.

Kline, Patrick, and Enrico Moretti. 2014. “Local Economic Development, Agglomeration Economies, and the Big Push: 100 Years of Evidence from the Tennessee Valley Authority.” Quarterly Journal of Economics 129, pp. 275–331.

Ludwig, Jens, et al. 2013. “What Can We Learn about Neighborhood Effects from the Moving to Opportunity Experiment?” American Journal of Sociology 114, pp. 144–188.

Neumark, David, and Jed Kolko. 2010. “Do Enterprise Zones Create Jobs? Evidence from California’s Enterprise Zone Program.” Journal of Urban Economics 68, pp. 1–19.

Neumark, David, and Helen Simpson. Forthcoming. “Place-Based Policies.” In Handbook of Regional and Urban Economics, volume 5, eds. Gilles Duranton, Vernon Henderson, and William Strange. Amsterdam: Elsevier.

Reynolds, C. Lockwood, and Shawn Rohlin. 2013. “The Effects of Location-Based Tax Policies on the Distribution of Household Income: Evidence from the Federal Empowerment Zone Program.” Unpublished manuscript, Kent State University.

Wilson, Daniel J. 2015. “Competing for Jobs: Local Taxes and Incentives.” FRBSF Economic Letter 2015-06 (February 23).

Opinions expressed in FRBSF Economic Letter do not necessarily reflect the views of the management of the Federal Reserve Bank of San Francisco or of the Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System. This publication is edited by Anita Todd and Karen Barnes. Permission to reprint portions of articles or whole articles must be obtained in writing. Please send editorial comments and requests for reprint permission to research.library@sf.frb.org