People of the United Kingdom voted to exit the European Union last June, a process dubbed “Brexit.” The persistent depreciation of the British pound since the vote suggests that U.K. economic conditions will be weakened over the long run following the separation from the EU. This projection of a persistent economic loss is based on the expected reversal of earlier gains from trade with other EU members and reduced cross-border labor flows.

On June 23, 2016, people of the United Kingdom voted to exit the European Union (EU), a process dubbed “Brexit.” According to polls and odds at betting sites, this outcome was unexpected, taking many, including financial market participants, by surprise. U.K. stock prices, real estate prices, and the British pound all took a dive in the wake of the announcement, and the pound remains well below its prevote level. In this Economic Letter we discuss fundamental macroeconomic forces that are likely to hold down U.K. economic growth and hence the value of the pound in the medium to long term.

The U.K. economy and Brexit

To understand the economic meaning of Brexit, it is useful to review some major aspects of EU membership as they apply to the United Kingdom. In addition to the free mobility of workers across borders, EU membership allows companies to move goods and services freely and to operate in all other member states, called passporting rights. By necessity, this requires a certain degree of harmonization of labor standards and regulation of markets for goods and services, with decisions adjudicated by the European Court of Justice. Not coincidentally, labor mobility, market regulation, and the European Court of Justice were three major aspects that Brexit supporters painted as harmful to the United Kingdom before the election.

One relevant distinguishing characteristic of the U.K. economy is the importance of its financial sector (McMahon 2016). Historically in the post-World War II period, a friendly regulatory climate for business in general and for the financial sector in particular led to the concentration of financial services in London. The efficiency gained from having industry know-how concentrated in a single location further contributed to London becoming one of the world’s largest financial centers. This specialization in financial services is apparent in U.K. international trade data. According to the most recent balance of payments data (Office for National Statistics 2016), in 2014 the country ran a trade surplus in financial services of 2.9% of GDP with the rest of the world, nearly half of that (1.2% of GDP) with the rest of the EU. By contrast, the United Kingdom ran a trade deficit in goods and other services of 4.9% of GDP, almost all of it (4.4% of GDP) with the rest of the EU.

The resulting wealth accumulation and improved quality of amenities has made London an attractive albeit expensive destination for skilled professionals. Over the years, EU passporting rights allowed global banks to establish their European headquarters in London and take advantage of these agglomeration effects, while relying on free mobility of labor to attract the necessary talent from all over the EU.

It was not clear immediately after the June 23 vote what form the new trade regime between the United Kingdom and the EU or the rest of the world would take. At one end of the spectrum is the so-called Norwegian model of paid access to the EU single market, which is closest to the current U.K. situation. However, this option was explicitly ruled out by Prime Minister Theresa May in her January 19, 2017, speech. At the other end of the spectrum is the so-called hard Brexit option, with little or no shared market access and significant restrictions on labor mobility, trade, and passporting rights. Other outcomes fall somewhere in-between. As of this writing, the hard Brexit option appears most likely, but details remain uncertain.

Exchange rate determination over the medium and long run

How does this all relate to the value of the pound? While there are many reasons for exchange rates to move on a day-to-day basis, over long periods of time exchange rates tend to respond to macroeconomic fundamentals.

In the long run, the real exchange rate, that is the relative purchasing power of a currency, is determined by the size and direction of a country’s external imbalances. Consider a borrowing country, one that consumes more than it produces and runs a trade deficit. Because a trade deficit means a net inflow of capital, the net demand for the borrowing country’s currency is high and its currency value must also be high. Conversely, a lending country that consumes less than it produces and runs a trade surplus has a net outflow of capital; thus, the net demand for that country’s currency is low and its currency value must also be low. For a given level of external imbalances, any increase in export prices relative to import prices, for instance due to a decline in the efficiency of the domestic economy, must be offset by a decline in the value of the domestic currency.

In addition, less productive countries, especially in the production of traded goods, also tend to have a more depreciated real exchange rate relative to more productive ones. Known as the Balassa-Samuelson effect, this results because lower productivity in tradable industries leads to lower real wages and lower prices of nontraded goods such as services relative to more productive countries.

In the short to medium run, financial market arbitrage connects the value of the currency today to prevailing interest rates and market expectations about the future value of the currency. Investors seeking high returns purchase assets of countries with high interest rates, thereby increasing the demand for and value of these countries’ currencies. Investors also buy more assets from countries whose currency is expected to appreciate. As a result, exchange rates react quickly to news about future exchange rates and interest rates. For example, news of weaker growth may raise expectations that the central bank will soon ease monetary policy, depressing the value of the currency today. This occurs because foreign exchange market participants, expecting that interest rates will decline and the currency will depreciate when monetary policy eases, adjust their portfolios immediately. Thus, the depreciation occurs at the time of the news, before the anticipated change. Expectations that a country’s currency will decline reduce the value of the currency today.

The implications are that the value of the pound today fluctuates in response to decisions by the Bank of England, investors’ expectations about future Bank of England decisions, and beliefs about the long-run value of the currency.

Why did the pound depreciate?

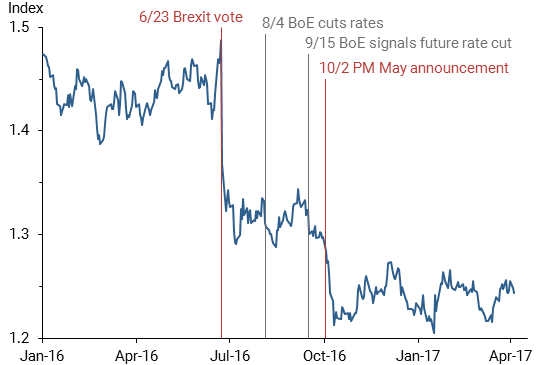

The pound depreciated sharply immediately following the Brexit vote (Figure 1, first vertical red line). This reflects market beliefs that Brexit would lead to a persistent decline in the real value of the pound. What could justify those beliefs?

Figure 1

Effects of events on pound sterling/dollar exchange rate

Even though there was no immediate economic slowdown after the vote, the potential exclusion from EU markets is likely to dampen potential growth in the United Kingdom in the coming years. Portes and Forte (2017) estimate that labor migration restrictions alone could lead to a 0.6% to 1.2% reduction in GDP by 2020. Before the vote, HM Treasury (2016) estimated that the long-term cost of separating from the EU would reduce GDP by 6% to 7.5% permanently, stating that “the U.K. would be permanently poorer if it left the EU.”

What will the impact of Brexit on the long-run real value of the pound be? At a fundamental level, Brexit is a deglobalization shock for the U.K. economy. By increasing barriers to trade, labor, and capital mobility, it will unravel some of the gains from trade in terms of increased specialization, efficiency, and productivity that the United Kingdom enjoyed as a member of the EU. In addition, the agglomeration effects that made London a preeminent global financial center will weaken. It is reasonable to expect that a post-Brexit United Kingdom will become both somewhat less specialized and less efficient. The corresponding decline in aggregate productivity will make its economy poorer than it would have been otherwise, which will weaken its currency.

This explains two distinct episodes of sharp depreciation of the pound in 2016: the June 23 vote itself and, when it became clear that Prime Minister May would proceed with Brexit on October 2. As market participants absorbed this news, they incorporated the expectations of lower future economic growth and a relatively less wealthy economy into their valuation of the pound.

If weaker growth were perceived as transitory, it might also trigger a more aggressive expansionary monetary policy by the Bank of England (BoE). In fact, the pound depreciated significantly on August 4, following the Bank’s interest rate cut, and again on September 15, when the Bank of England indicated that additional rate cuts were likely in the future (gray lines in Figure 1). The most recent projections from the Bank of England (2017) have revised expected policy rates downwards compared with those projected for the United States and other economies, potentially putting downward pressure on the pound.

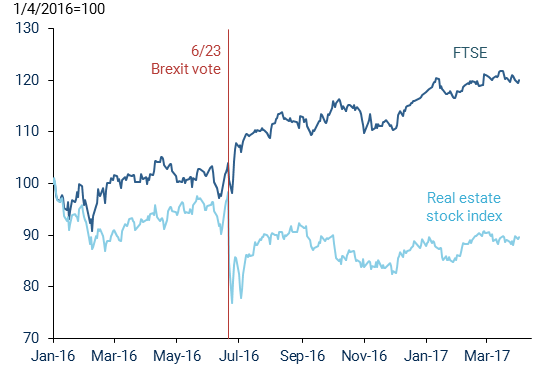

Other market developments are consistent with this interpretation of the decline in the value of the pound. According to the Balassa-Samuelson effect, the values of products traded more domestically, such as real estate, should fall relative to those traded more internationally. Moreover, if some global financial companies decide to move out of London, demand for office and residential space will recede. U.K. corporate and residential housing will become a less traded good. Indeed, as Figure 2 shows, the real estate stock index shows a sharp and persistent decline following the vote relative to the overall market index (FTSE).

Figure 2

U.K. overall and real estate stock prices

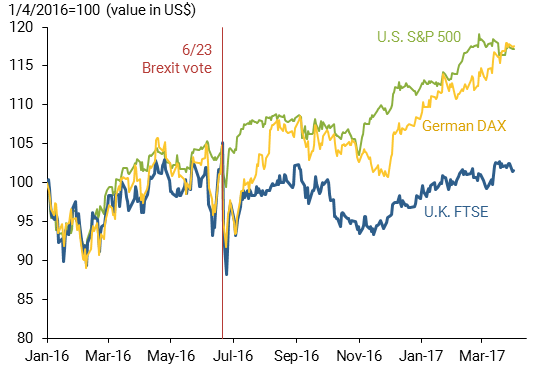

Given that the stock market captures investors’ long-run expectations, one might be surprised that the broad U.K. stock market index rebounded strongly after the initial drop in the wake of the vote. However, as Figure 3 demonstrates, the FTSE lost significant ground relative to the U.S. Standard & Poor’s 500 and German DAX when measured in U.S. dollar terms.

Figure 3

U.K., U.S., and German stock indexes valued in U.S. dollars

Beyond the fundamental reasons for the pound’s long-term decline, investors may also become more concerned about the nation’s ability to finance its trade deficit in the short term, which would also lower the value of the pound (Corsetti and Muller 2016).

Concluding thoughts: Near-term versus longer-term effects

The depreciation of the pound is not necessarily harmful to the British economy in the near term, however. A weaker pound gives a boost to both exporting and import-competing industries. One expected immediate effect of Brexit will be to stimulate the manufacturing sector at the expense of the financial industry. Moreover, the depreciation of the pound provides a one-time valuation gain for foreign currency-denominated assets held by U.K. residents. Calculations in Forbes, Hjortsoe, and Nenova (2016) using post-Brexit data suggest the depreciation has improved the United Kingdom’s net international investment position by roughly 25% of GDP, a significant windfall.

Yet, despite a possible boost to manufacturing exports and some valuation gains, the depreciation of the pound since the Brexit vote must reflect expectations of slower growth for the U.K. economy in the next few years and beyond. While some groups may gain from Brexit, the message from the foreign exchange and asset markets is clear: The overall size of the economy will eventually shrink relative to what it could have been if the United Kingdom had voted to stay in the EU.

Pierre-Olivier Gourinchas is a professor of economics and director of the Clausen Center for International Business and Policy at the University of California, Berkeley.

Galina Hale is a research advisor in the Economic Research Department of the Federal Reserve Bank of San Francisco.

References

Bank of England. 2017. “Inflation Report.” February.

Corsetti, Giancarlo, and Gernot Muller. 2016. “The Pound and the Macroeconomic Effects of Brexit.” Vox EU, June 18.

Forbes Kristin, Ida Hjortsoe, and Tsvetelina Nenova. 2016. “Current Account Deficits during Heightened Risk: Menacing or Mitigating?” Bank of England External MPC Unit Discussion Paper 46.

HM Treasury. 2016. “The Long-Term Economic Impact of EU Membership and the Alternatives.” April.

McMahon, Michael. 2016. “The Implications of Brexit for the City.” In Brexit Beckons: Thinking Ahead by Leading Economists, ed. Richard Baldwin. London: VoxEU, CEPR Press.

Office for National Statistics. 2016. “UK Balance of Payments, the Pink Book: 2016.” July 29.

Portes Jonathan, and Guiseppe Forte. 2017. “The Economic Impact of Brexit-Induced Reductions in Migration to the UK.” Vox EU, January 5.

Opinions expressed in FRBSF Economic Letter do not necessarily reflect the views of the management of the Federal Reserve Bank of San Francisco or of the Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System. This publication is edited by Anita Todd and Karen Barnes. Permission to reprint portions of articles or whole articles must be obtained in writing. Please send editorial comments and requests for reprint permission to research.library@sf.frb.org