Some reports blame opioid use for part of the decline in labor force participation among adult men. Estimates based on workers’ compensation data shed light on the relationship between opioid prescriptions and the return to work among people who suffer work-related low-back injuries, for which opioid use is common. Differences in opioid prescribing patterns across locations demonstrate how various use of these medications can impact how quickly workers return to work. When opioids are prescribed for longer-term treatment, workers have considerably longer durations of temporary disability following an injury.

When used in accordance with evidence-based guidelines, opioids can help health-care professionals provide compassionate care for injured workers. However, what began as an effort to improve pain relief has developed into an opioid crisis of epidemic proportions (U.S. Department of Health and Human Services 2018). Aside from the direct adverse effects of opioid use and addiction, there may be important consequences for key economic outcomes. Indeed, some speculate that the rising use of opioids has contributed to the decline in U.S. labor force participation of men (Krueger 2017).

We study the effects of opioids on employment in the setting of workers’ compensation, using extensive and detailed data about workers’ injuries, medical treatment, and return to work following an injury. In this Economic Letter, we discuss new evidence on the relationship between opioid prescriptions and a proxy for the amount of time before injured workers return to work—the “duration of temporary disability.” Estimating the effects of opioids on return to work is challenging because other factors—such as injury severity—can drive both opioid use and return to work. We address this problem by using variations in opioid prescribing across small regions to mimic an “experiment” in which prescriptions for opioids differ for otherwise identical workers with similar injuries and jobs.

Background on opioids and work injuries

Opioid use is common among workers injured at work. Recent studies show that more than half of injured workers who are off work for more than seven days with pain medications and did not have surgery received an opioid prescription, many on a longer-term basis (Thumula, Wang, and Liu 2017). This raises the question: Given the risks from opioids, are there important benefits that might make the trade-off worthwhile? We focus on a key potential benefit from the point of view of workers’ compensation policy, the duration of disability. Although some of the adverse effects of opioid use would be expected to lengthen the duration of disability, there could also be some benefits, via pain reduction, that enable a faster return to work. To address this question, we examine the relationship between multiple measures of opioid prescribing and the time that injured workers spend on temporary disability benefits while recovering from an injury.

Work-related injuries represent a substantial share of injuries that occur among working adults. Nearly half of all trauma injuries for this group are work related and covered by workers’ compensation insurance; one in five injuries for soft tissue conditions are work related (Victor, Fomenko, and Gruber 2015). This suggests that the workers’ compensation system represents a consequential portion of the opioids prescribed to working-age adults.

Estimating the effect of opioid prescriptions on the duration of temporary disability

There is a relationship between opioid prescriptions and longer durations of temporary disability benefits. However, the direction of causation is not clear. For example, prescribing opioids for more severe injuries could independently lead to an association between opioid prescriptions and longer durations of disability. Opioid prescriptions may also be related to worker characteristics that result in longer time away from work unrelated to the prescription. Conversely, workers may choose to use opioids to speed up their return to work. Thus, we need to analyze the cause and effect relationship.

In recent work, we use a new research strategy to estimate the causal effect of opioid prescriptions on the duration of disability (Savych, Neumark, and Lea 2018). We focus on low-back injuries, which are common claims in workers’ compensation and exhibit a higher use of opioids—including the longer-term prescriptions on which we focus—than most other injuries (Thumula et al. 2017). In addition, evidence-based treatment guidelines recommend against long-term use of opioids for most of these cases, suggesting that some prescriptions may be excessive. Finally, our focus on a single type of injury makes it easier to compare workers with similar injury severity, and hence ensure that the variation in prescriptions is not driven by differences in type of injury or injury severity. Nonetheless, the results are similar when we do not restrict our analysis to low-back injuries.

To estimate the effects of longer-term opioid prescriptions, it is important to acknowledge potentially conflicting factors, such as injury characteristics and the mix of local jobs, that can affect both prescriptions and the speed of return to work. However, local prescribing patterns affect longer-term opioid prescriptions directly but do not independently affect return to work. Our strategy isolates the variation in prescriptions attributable to these patterns. Hence we can purge the influence of individual worker or provider preferences, injury severity, the local job mix, and other factors that could confound the empirical relationship between opioids prescribing and return to work.

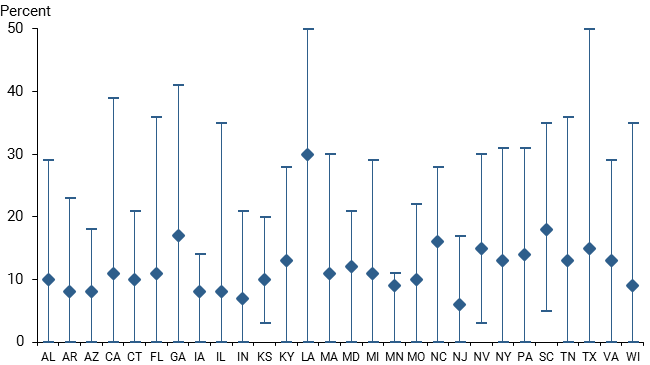

Our strategy uses the fact that local prescribing patterns vary substantially. For example, Figure 1 shows that hospital services markets—defined by hospital referral regions (HRRs)—demonstrate extensive variation both across states and within states in the percentage of low-back injuries that are treated with longer-term opioid prescriptions.

Figure 1

Longer-term opioid prescriptions as percent of injury treatments by state

Source: Savych, Neumark, and Lea (2018).

Note: Data reflect results across hospital referral regions (HRRs) within a state for 28 states from October 2008 through September 2013. Data show percentage of low-back injuries that receive longer-term opioid prescriptions; diamond markers show averages and top and bottom bar markers show maximums and minimums across HRRs for each state in the sample.

Despite this strategy, we might not fully uncover the causal effect of opioid prescriptions. For example, the industry mix of jobs in an area could influence both the speed of return to work and how providers treat injuries. Or other differences in workers’ compensation systems could influence both return to work and prescribing behavior. We systematically address such concerns in Savych et al. (2018) and conclude that they have little impact on our findings.

Evidence

We find no evidence that workers with any opioid prescription had longer duration of temporary disability; the estimate for this broader group is close to zero and statistically insignificant. Similarly, if we simply look at workers who received multiple prescriptions or prescriptions for a large opioid amount, the effect is not statistically distinguishable from zero.

The key difference is when we look at longer-term opioid prescriptions, defined as having opioid prescriptions within the first three months after an injury and three or more filled opioid prescriptions between the 7th and 12th months after an injury. This definition is intended to capture a very different kind of prescribing behavior than, say, prescribing opioids for short-term relief following surgery. When we characterize workers by whether they had longer-term opioid prescriptions, there is a strong effect lengthening the duration of temporary disability benefits—our proxy for time out of work. Workers with longer-term opioid prescriptions had durations of temporary disability that were 251% longer—more than triple the duration of similar workers with similar injuries who were not prescribed opioids. The finding is similar when we look at workers who received longer-term prescriptions for large amounts of opioids.

One can interpret these estimates as the effect of a policy change that eliminated longer-term opioid prescriptions. However, a more sensible policy question might be: What is a reasonable expectation for policy to actually reduce longer-term opioid use and, if such a policy succeeded, how much would we expect the duration of temporary disability benefits to fall? To get a handle on this question, consider a 5 percentage point decrease in longer-term opioid prescriptions among workers with low back injuries, from an average of 12% to 7% of cases. This decrease is a plausible policy effect, based on evidence from legislation in Kentucky aimed at reducing opioids through a prescription monitoring database, limiting the amounts prescribed, and educating providers (Thumula, 2017); the policy led to a 10 percentage point decline in claims with pain medications that included any opioids, and a 6 percentage point decline in claims with pain medications that had two or more opioid prescriptions. Based on our estimates, applying a similar policy change nationally across the states in our sample would translate to a 12.6% decrease in the duration of temporary disability, resulting in an average of 2.8 weeks shorter temporary disability for workers with low-back injuries.

Conclusions

In this Letter, we find that prolonged prescribing of opioids leads to longer duration of temporary disability benefits among workers with work-related low-back injuries. Our estimates indicate that longer-term opioid prescriptions roughly triple the duration of temporary disability benefits, compared to similar workers with similar injuries who do not get longer-term opioid prescriptions. On average, we do not find evidence of beneficial effects from opioids prescribed in workers’ compensation cases in the form of easing an individual’s return to work. One caveat is that, although we use a research strategy that should identify the causal effect of opioid prescriptions, without a true randomized experiment we cannot completely discount the possibility that our evidence reflects noncausal factors.

These findings suggest that—especially because longer-term prescribing of opioids is not typically recommended for low-back pain cases (ACOEM, 2008)—policymakers should do more to understand why workers are receiving opioids on a longer-term basis. In this way, policy interventions can be targeted toward reducing inappropriate longer-term use. Some states, including Florida, Texas, Kentucky, and Washington, have already implemented such policy changes, and research findings such as ours may help guide further interventions.

Our evidence cannot directly address what role opioids play overall in changes in labor force participation. However, our results are consistent with the effects of opioid prescriptions contributing to lower participation by lengthening the time injured workers remain out of work.

David Neumark is Distinguished Professor of Economics at the University of California, Irvine, a visiting scholar at the Federal Reserve Bank of San Francisco, and senior research fellow at the Workers Compensation Research Institute (WCRI).

Bogdan Savych is a public policy analyst at WCRI.

The views expressed are the authors’ and do not necessarily reflect those of WCRI or the Federal Reserve Bank of San Francisco.

References

American College of Occupational and Environmental Medicine (ACOEM). 2008. “Practice Guidelines Chronic Pain Chapter, revised 2008.” ACOEM, Elk Grove Village, IL.

Krueger, Alan B. 2017. “Where Have All the Workers Gone? An Inquiry into the Decline of the U.S. Labor Force Participation Rate.” Brookings Papers on Economic Activity, Fall, pp. 1–59.

Savych, Bogdan, David Neumark, and Randy Lea. 2018. The Impact of Opioid Prescriptions on Duration of Temporary Disability. Report WC-18-18, Workers Compensation Research Institute, Cambridge, MA.

Thumula, Vennela. 2017. Impact of Kentucky Opioid Reforms. Report WC-17-31, Workers Compensation Research Institute, Cambridge, MA.

Thumula, Vennela, Dongchun Wang, and Te-Chun Liu. 2017. “Interstate Variations in Use of Opioids, 4th edition.” Report WC-17-28, Workers Compensation Research Institute, Cambridge, MA.

U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. 2018. “What Is the U.S. Opioid Epidemic?” Accessed September 19.

Victor, Richard, Olesya Fomenko, and Jonathan Gruber. 2015. “Will the Affordable Care Act Shift Claims to Workers’ Compensation Payors?” Report WC-15-26, Workers Compensation Research Institute, Cambridge, MA.

Opinions expressed in FRBSF Economic Letter do not necessarily reflect the views of the management of the Federal Reserve Bank of San Francisco or of the Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System. This publication is edited by Anita Todd and Karen Barnes. Permission to reprint portions of articles or whole articles must be obtained in writing. Please send editorial comments and requests for reprint permission to research.library@sf.frb.org