Labor force participation among U.S. men and women ages 25 to 54 has been declining for nearly 20 years, a stark contrast with rising participation in Canada over this period. Three-fourths of the difference between the two countries can be explained by the growing gap in labor force attachment of women. A key factor is the extensive parental leave policies in Canada. If the United States could reverse the trend in participation of prime-age women to match Canada, it would see 5 million additional prime-age workers join the labor force.

The decline in labor force participation of U.S. men and women ages 25 to 54 stands in stark contrast with other industrialized nations, where participation rates for prime-age workers have increased over time. In this Economic Letter, we show how labor force participation rates have diverged for men and women in the United States and Canada. We find that three-fourths of the difference in participation between the two countries can be explained by the growing gap in labor force attachment of women. We discuss how employment and social policies in Canada have made it easier for women to remain in the labor force while raising children. Our findings suggest that policy interventions to reduce the structural barriers that keep many women on the sidelines could bring millions of prime-age Americans into the labor force.

U.S. labor participation is falling behind

The labor force participation rate (LFP) is defined as the fraction of the working-age (16 and older) population who are working or actively looking for work. Although many things influence participation rates, one of the primary determinants is age. For example, rates are lower for younger workers, ages 16 to 24, who are finishing schooling and for older workers, 55+, who are beginning to retire. A common way to abstract from these effects is to study labor force participation for people in their prime working years, ages 25 to 54. This allows us to more directly consider the other important factors affecting labor decisions.

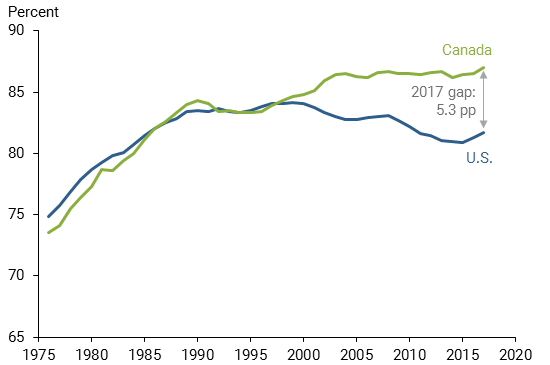

Figure 1 shows annual labor force participation rates for prime-age men and women in the United States and Canada from 1976 through 2017. The rates for both countries tracked closely for many years, rising steadily through 1991. This reflected the large-scale entry of prime-age women into the labor force. Growth slowed in both countries in the early 1990s, reaching nearly identical rates of 84%.

Figure 1

U.S., Canada prime-age labor participation, 1976–2017

Source: Current Population Survey (U.S.) and Labor Force Survey (Canada).

Since then, rates in the two countries have moved in opposite directions. U.S. prime-age workers have steadily withdrawn from the labor force, while labor force participation in Canada has gradually increased. These divergent trends have resulted in a substantial difference in the share of prime-age workers working or looking for work in the two countries. In 2017, 87% of prime-age workers in Canada participated in the labor market, compared with 81.7% in the United States, a 5.3 percentage point (pp) gap.

Drivers of the difference

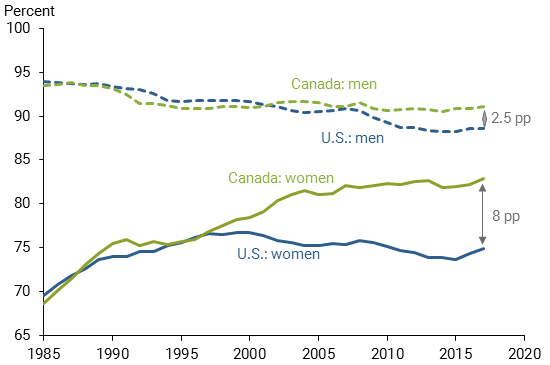

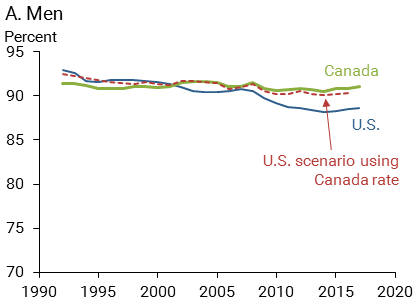

To better understand what might be behind the divergence in Figure 1, we compared participation rates for men and women separately. Figure 2 shows U.S. and Canadian participation rates by gender from 1985 through 2017 and reveals several interesting patterns. Among men, overall participation rates remained roughly similar in both countries until the Great Recession. U.S. men show a much sharper decline following the recession, and the recovery also has been slower and less complete. The net effect is a 2.5 percentage point gap in U.S.-Canadian prime-age male labor force participation in 2017.

Figure 2

Canada and U.S. prime-age labor participation by gender

Source: Current Population Survey (U.S.) and Labor Force Survey (Canada).

The patterns for women show notable differences from men in both the timing and the magnitude of the disparity in participation rates. First, the rate divergence between U.S. and Canadian prime-age women started much earlier, in the mid-1990s. Second, the emerging gap was the result of steady increases in labor force participation among Canadian women and steady declines in participation among U.S. women. The impact of these opposing trends is striking. In 1997, participation among women in the United States and Canada was nearly identical, close to 77%. By 2017, participation for Canadian women had risen to 83% while that for U.S. women had fallen to 75%, leaving an 8 percentage point gap. In fact, three-fourths of the divergence in labor market participation rates of prime-age workers between the two countries is explained by the gap in the participation rates of women, underscoring the importance of this difference.

Differences in participation by education

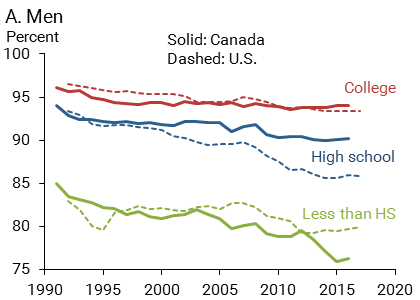

Research on labor market outcomes has found a strong link between educational attainment and labor force participation: more-educated workers participate at higher rates than less-educated workers. The link between education and labor force attachment is immediately apparent in Figure 3, which reports participation rates among workers of three levels of educational attainment for men and women in the United States and Canada: college degree, high school diploma, and less than high school diploma.

Figure 3

Labor force participations rates by educational attainment, 1990 to 2016

Source: Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD).

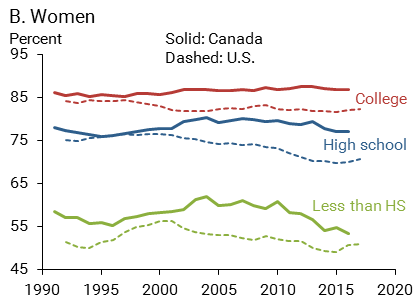

Both the United States and Canada had nearly identical rates of participation across levels of education in the early 1990s. Men in both countries experienced declining rates of participation during this period (Figure 3, panel A). However, the downward trend for men with a high school education was more pronounced in the United States, especially during the Great Recession. Another way to frame this is to consider what labor force participation would have been if prime-age men in the United States had the same rate of labor participation by educational attainment level as Canada. In this scenario, the dashed line in Figure 4, panel A reveals that nearly the entire gap in the participation of men between the two countries would be explained by the drop in participation of workers with a high school education.

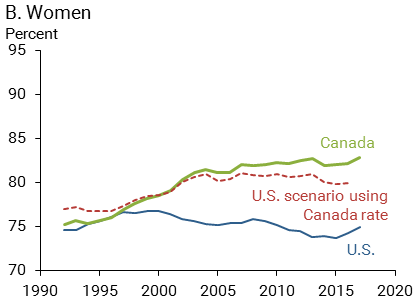

Figure 4

Scenario applying Canada labor participation rates by education to the United States

Source: Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD).

Turning to women, the differences in labor market participation for those with a high school and a college education across the two countries is striking (Figure 3, panel B). While similar in their attachment to the labor market up to the late 1990s, college-educated women in Canada continued to enter the labor force at a greater rate throughout the 2000s. In 2016, 87% of Canadian women with a college degree were in the labor market. Conversely, participation for U.S. college-educated women began to decline at the end of the 1990s and stood at 82% in 2016, 5 percentage points below college-educated Canadian women. Women with a high school education showed a similar divergence, with a 7 percentage point gap by 2016. The scenario asking what labor force participation would have been if prime-age women in the United States had the same rate of labor participation by educational attainment as Canada is very instructive. The dashed line in Figure 4, panel B reveals that most of the gap can be explained by the differences by education level. These differences at higher levels of education will be compounded in the future by the increasing gap in educational attainment between the two countries.

Overall, three-fourths of the gap in participation of prime-age workers between the two countries can be explained by the gap among prime-age women. If U.S. women of every level of educational attainment were to reach the participation level of Canadian women, the gap between women in the two countries would drop by 70% and U.S. women’s participation rate would rise from 74% to 80%.

What could account for the difference in behavior?

Over the past several decades, many industrialized countries have expanded policies to make it easier for women, particularly mothers, to stay in the labor force. A 1988 tax reform in Canada reduced the marginal tax rate of a second earner in a household. This had little effect on women’s labor supply, although part-time work by married women increased modestly for a time (Crossley and Jeon 2007). Since the mid-1990s, part-time employment for Canadian women has been on a downward trend and is currently at a level similar to their U.S. counterparts. Several other countries have promoted flexible work arrangements, which helps explain part of the gap in female participation between the United States and some industrialized countries (see Cascio et al. 2015), but not with Canada.

Two other sets of policies aimed directly at supporting parental attachment to the labor force have followed significantly different paths in the United States and Canada over this period: subsidizing childcare costs and parental leave.

The extent and availability of government subsidies for the cost of childcare varies greatly across Canadian provinces. Quebec, for instance, introduced universal childcare in the late 1990s. Typical monthly preschool fees in Montreal in 2015 were about CA$174 per month in Montreal, and CA$1,033 in Toronto (MacDonald and Klinger 2015). However, research on whether such policies have affected the labor participation decisions of mothers has found little evidence of their effectiveness. Rather, new plans simply replace existing childcare arrangements (Havnes and Mogstad 2011). Cascio and Schanzenbach (2013), for instance, found that universal preschool programs offered in Georgia and Oklahoma since the 1990s had little impact on the likelihood of mothers working.

Parental leave policies in Canada provide strong incentives to remain attached to the labor force following the arrival of a new child: a person’s job is protected with the same wages and benefits continuing to accrue during the leave, and a system of benefits funded out of employment insurance provides income replacement during the leave. Thus, a parent on leave maintains a continuous employment relationship, and this protection can last for up to 78 weeks in combination with existing maternal leave (with some variation across provinces).

Current parental leave policies in Canada arrived in several waves beginning in the late 1970s. This timing, along with variations in the timing of expansions across different provinces, has allowed research to track the positive effects of parental leave on mothers’ labor force participation rates (Baker et al. 2008). This is consistent with evidence on the effect from other countries’ leave programs compared with the limited policies available in the United States (Blau and Kahn 2013).

Summing up

The contrast between the incentives Canada and the United States offer prime-age workers to remain attached to the labor force is clear. A large pool of skilled potential workers could be encouraged to join the labor market with the right set of policies. By reversing the trend in participation of prime-age women to catch up with Canada’s labor market participation rate, the United States could add as many as 5 million prime-age workers to its labor force.

Mary C. Daly is president and chief executive officer of the Federal Reserve Bank of San Francisco.

Joseph H. Pedtke is a PhD student in economics at the University of Minnesota and a former research associate at the Federal Reserve Bank of San Francisco.

Nicolas Petrosky-Nadeau is a senior research advisor in the Economic Research Department of the Federal Reserve Bank of San Francisco.

Annemarie Schweinert is a PhD student in economics at the University of Wisconsin-Madison and a former research associate at the Federal Reserve Bank of San Francisco.

References

Baker, Michael, and Kevin Milligan. 2008. “How Does Job-Protected Maternity Leave Affect Mothers’ Employment?” Journal of Labor Economics 26(4), pp. 655–691.

Blau, Francine D., and Lawrence M. Kahn. 2013. “Female Labor Supply: Why Is the United States Falling Behind?” American Economic Review: Papers and Proceedings 103 (3), pp. 251–256.

Cascio, Elizabeth, Steven Haider, and Helena Skyt Nielsen. 2015. “The Effectiveness of Policies That Promote Labor Force Participation of Women with Children: A Collection of National Studies.” Labour Economics 36, pp. 64–71.

Cascio, Elizabeth, and Diane Whitmore Schanzenbach. 2013. “The Impacts of Expanding Access to High-Quality Preschool Education.” Brookings Papers on Economic Activity, Fall, pp. 127–178.

Crossley, Thomas F., and Sung-Hee Jeon. 2007. “Joint Taxation and the Labour Supply of Married Women: Evidence from the Canadian Tax Reform of 1988.” Fiscal Studies 28(3), pp. 343–365.

Havnes, Tarjei, and Magne Magstad. 2011. “Money for Nothing? Universal Childcare and Maternal Employment.” Journal of Public Economics 95, pp. 1,455–1,465.

Macdonald, David, and Thea Klinger. 2015. “They Go Up So Fast: 2015 Child Care Fees in Canadian Cities.” Canadian Centre for Policy Alternatives Report, December.

Opinions expressed in FRBSF Economic Letter do not necessarily reflect the views of the management of the Federal Reserve Bank of San Francisco or of the Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System. This publication is edited by Anita Todd and Karen Barnes. Permission to reprint portions of articles or whole articles must be obtained in writing. Please send editorial comments and requests for reprint permission to research.library@sf.frb.org