A new and less familiar economic environment has emerged in the United States and other countries. Our collective futures now include slower potential growth, lower long-term interest rates, and persistently weak inflation. This new landscape demands we think differently about how to balance and achieve price stability and full employment objectives. The following is adapted from a speech by the president and CEO of the Federal Reserve Bank of San Francisco to the conference “Inflation Targeting—Prospects and Challenges” in Wellington, New Zealand, on August 29.

I’m delighted to be here in my capacity as president and CEO of the Federal Reserve Bank of San Francisco—and to help mark the 30th anniversary of New Zealand’s commitment to an explicit inflation-targeting regime. It was the first of its kind and has influenced central banks around the world.

But to be effective, monetary policymaking must continually evolve. We live in a dynamic world that demands we remain humble about what we know—and curious about what we might learn.

New Zealand is a great example of this. You haven’t been complacent during the past 30 years. Indeed, you recently moved to an explicit dual mandate—one that requires both price stability and full employment.

This is a framework we have a lot of history with in the United States. So you might think I will be providing some lessons from our experience with balancing these two objectives.

And I’d like to. But the situation isn’t that simple. The world has changed since we first took on a dual mandate more than 40 years ago. And things are different. In the United States, here in New Zealand, and in countries around the world, a new—and less familiar—economic environment has emerged.

Our collective futures now include slower potential growth, lower long-term interest rates, and persistently weak inflation. This new landscape demands we think differently about how to balance and achieve our price stability and full employment objectives. Today I will share how I’m thinking about these issues from my seat at the San Francisco Fed.

A new economic environment

To understand the new environment we face, we first have to look back to the past. And here I will use the United States as an example.

When I started working at the Federal Reserve in 1996, I learned three important facts—the “deep” parameters of central banking. First, the potential growth rate of the U.S. economy averages around 3.5%. Second, the real neutral rate of interest—or r-star—changes over time but is well-bounded away from zero, mostly in the range of 2% to 3% or higher (Congressional Budget Office 2019, Laubach and Williams 2003, FRB New York 2019, Christensen and Rudebusch 2019). Third, unemployment and inflation are strongly linked through the Phillips curve.

Fast forward to 2019. These facts—these deep parameters—feel like a distant memory. As of June, participants of the Federal Open Market Committee put longer-run potential growth in the United States at about 1.9%. Estimates of the long-run neutral rate of interest were penciled in at just 0.5% (Board of Governors 2019b). As for the Phillips curve, most arguments today center around whether it’s dead or just gravely ill. Either way, the relationship between unemployment and inflation has become very difficult to spot.

Although the numbers may be a little different, the changes I’ve described are not unique to the United States. Global demographic shifts and lower productivity gains are tempering growth and reducing long-run interest rates in many countries (Holston, Laubach, and Williams 2017). And a number of central banks are finding that inflation is less responsive to labor market improvements than in the past.

These trends have important implications for monetary policy. Lower r-star and the zero lower bound mean we’ll have less room to maneuver when the next downturn occurs. One of the lessons learned from the financial crisis and its aftermath is that alternative tools like forward guidance and the balance sheet can be effective at stimulating economies. However, they’re still imperfect substitutes for the most effective tool at our disposal: traditional interest rate adjustments. And the fainter signal coming from the Phillips curve means we have less direct, real-time feedback about how monetary policy is playing out in the economy.

In other words, the jobs of central banks have gotten harder.

Uncertainty and tradeoffs

When I lay out the backdrop I just described, I’m almost always asked the same questions. First, if inflation isn’t rising, can we run the economy as hot as we want without consequence? And second, does monetary policy really affect inflation anymore?

Let me tackle the hot economy question first.

Despite many years of trying, I’ve been unable to find evidence of a “free lunch.” Actions always have consequences, and there are always tradeoffs to consider. Some are immediate, and some take time to develop.

The question is, what are the tradeoffs in today’s economic environment? If the normal tension between unemployment and inflation has weakened, how do we know whether we’ve achieved our full employment mandate?

Again I’ll turn to the U.S. experience. Our current expansion passed the 10-year mark in July—a U.S. record. Unemployment has fallen from 10% at its peak in October 2009 to near historic lows—just 3.7% in July. Other critical labor market indicators have also improved, including prime-age labor force participation, job-finding rates, wages, and income.

These improvements have been particularly notable for disadvantaged workers who often struggle to get a foothold in the workforce (Petrosky-Nadeau and Valletta 2019). Recent research I’ve done with colleagues examines this pattern closely (Aaronson et al. 2019). We looked into whether running a hot economy—compared with just a sustained expansion—provides extra benefits to marginalized groups.

We found that, when the unemployment rate drops below what is thought to be its long-run sustainable level, the benefits to marginalized groups increase. Said simply, the gains to running a hot economy disproportionately flow to groups that are historically less advantaged.

These findings are echoed in the comments we hear from workforce development and community leaders. They tell us that the current hot economy has allowed many of their constituents to get a second look from employers (Powell 2019).

This outcome is intuitive. When labor markets are tight and firms are competing for workers, they find new ways to fill jobs. They recruit more intensively, adjust hiring standards, and look to a broader pool of potential employees (Okun 1973; Davis, Faberman, and Haltiwanger 2013; Leduc and Liu 2019; Abraham and Haltiwanger 2019; and Modestino, Shoag, and Ballance 2016). These conditions create more opportunities for disadvantaged groups.

All of this means that assigning too much weight to our projections of the long-run sustainable rate of unemployment—or u-star—risks undershooting what the labor market can really deliver. Indeed, central banks in the United States and other countries have been marking down their estimates of u-star as unemployment rates have fallen (Board of Governors 2012, 2019b). And recent research in the United States and here in New Zealand points to non-inflationary rates of unemployment that are even lower than current estimates of the natural rate would imply (Petrosky-Nadeau and Valletta 2019; Crump et al. 2019; and Jacob and Wong 2018).

But as I said before… there is no free lunch. There are potential consequences to running a hot economy we need to consider.

For instance, an overly tight labor market might encourage businesses and workers to make decisions that have negative long-term effects on potential output. Some research has found that persistently strong economic conditions can pull young people out of school—a choice that may undermine their future job prospects and earning potential (Charles, Hurst, and Notowidigdo 2018; and Cascio and Narayan 2019). And anecdotal evidence suggests that firms may reduce investments in employee training and skill development to reduce the costs of rapid employee turnover.

We also have to think about how running the economy hotter affects financial stability. If interest rates get too low, and borrowing becomes too easy, imbalances in financial markets could once again develop. In the United States, I’m closely watching the high level of corporate debt, particularly among riskier firms. While I don’t view current corporate indebtedness as posing an acute financial stability risk, this vulnerability could amplify the macroeconomic impact of any shocks to the economy.

So we need to stay vigilant. But for now, the latest Federal Reserve Financial Stability Report judges that the U.S. financial sector remains resilient (Board of Governors 2019a). And if vulnerabilities were to increase further, there are instruments such as the countercyclical capital buffer that we might want to consider before making monetary policy more restrictive.

Putting this all together, where do I come out on the tradeoffs of running a hot economy? Right now, with little inflationary pressure and considerable uncertainty about the threshold for full employment, I’m biased towards including as many workers as possible in the expansion.

Every tenth counts

Now let me turn to the second question: Can monetary policy still affect inflation?

Looking at the data does give one pause. Inflation rates in many countries have remained stubbornly below 2% for more than a decade. This is despite considerable monetary stimulus and relatively healthy labor markets.

Now, some would argue that these misses are not really meaningful – just a couple of tenths. But in our new economic environment, every tenth counts. There are a number of difficulties that could arise with persistent misses on our 2% goal.

One of the most important benefits of inflation targeting was that it resulted in well-anchored inflation expectations. Households and firms became willing to smooth through idiosyncratic price shocks rather than incorporate them into wage demands or long-term contracts. This success is reflected in the research that shows expectations, rather than past inflation, have become the key determinant of future inflation (Jordà et al. 2019; and International Monetary Fund 2013).

But like most things, expectations can cut both ways. If we consistently fall short of our inflation target, expectations will drift down. We’re already seeing signs of softness in survey- and market-based measures of longer-run inflation expectations (Nechio 2015; and Lansing 2018).

Persistent misses on inflation will make the public more likely to incorporate these delivered outcomes into their plans. The anchor we worked so hard to achieve will move from the 2% target we talk about to the less than 2% inflation we deliver.

This is particularly worrisome given the proximity of the effective lower bound. Below-target inflation translates directly into less policy space to offset negative economic shocks. In very practical terms, if inflation expectations are a quarter point below our target when the next downturn arrives—and so are nominal interest rates—that’s one less rate cut at our disposal.

Monetary policy in a changing world

Looking ahead, persistently low inflation presents a new problem for monetary policymakers.

Thirty years ago, central banks around the world needed to tamp down rising inflation. The Reserve Bank of New Zealand responded by boldly introducing inflation targeting as a new monetary policy framework. Others quickly followed. These flexible inflation-targeting regimes played a large role in bringing inflation under control and in anchoring inflation expectations.

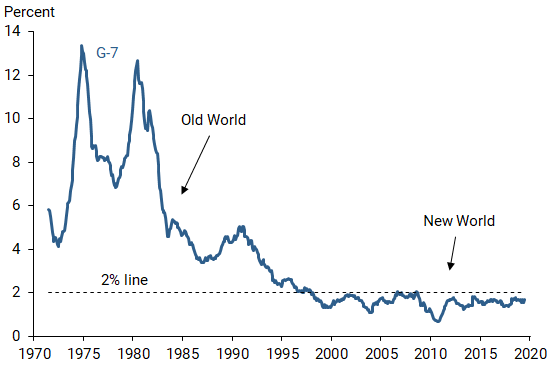

Today, we’re fighting a different battle. We’re fighting inflation from below our target. Figure 1 shows how dramatic the change has been.

Figure 1

Core CPI inflation, average for G-7 countries

Note: 12-month change in core consumer price index inflation.

Source: Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development.

As central bankers, we have to ask ourselves: Are we powerless to respond to these new dynamics? Or do we simply need new tools?

Our current tool, flexible inflation targeting, is by design forgetful. It lets bygones be bygones and makes no attempt to make up for past inflation misses. This worked well when inflation shocks were tilted to the upside and we had plenty of policy space to offset unwanted increases.

In our new world of low inflation and low r-star, this approach has clear challenges. It runs the risk of repeatedly delivering below-target inflation during expansions and leaving the economy with even less policy space when the next downturn hits.

Alternative strategies such as average inflation targeting and price-level and nominal income targeting explicitly include a makeup strategy. They ensure inflation misses balance out over time. While no magic bullet, these makeup approaches recognize that we’ll need to be intentional—rather than opportunistic—about offsetting inflation underruns (Svensson 1999; Nessén and Vestin 2005; Bernanke, Kiley, and Roberts 2019; and Mertens and Williams 2019).

Of course, any changes in our monetary policy framework require careful and deliberate thought. The current approach has been effective in keeping inflation low and steady through good times and bad. So the bar for change should be high.

But the future looks different than the past. And much like 30 years ago, the world we face today requires us to consider bold action. For now, we must fully use the tools we have. And looking ahead, we must adapt our monetary policy frameworks to deliver on the mandates we’re committed to: full employment and price stability.

Conclusion

There’s no question that our world has changed tremendously in recent years. And these changes have created challenges that we’re still learning how to address. But we’re working from strong foundations. Foundations that the Reserve Bank of New Zealand helped lay down 30 years ago.

I look forward to figuring out where we go next with you. Thank you.

Mary C. Daly is president and chief executive officer of the Federal Reserve Bank of San Francisco.

References

Aaronson, Stephanie R., Mary C. Daly, William Wascher, and David W. Wilcox. 2019. “Okun Revisited: Who Benefits Most From a Strong Economy?” BPEA Conference Draft, March 7–8. Forthcoming in Brookings Papers on Economic Activity.

Abraham, Katharine G., and John C. Haltiwanger. 2019. “How Tight Is the Labor Market?” Manuscript prepared for the Conference on Monetary Policy Strategy, Tools, and Communication Practices: Fed Listens Event hosted by Federal Reserve Bank of Chicago, June 3–4.

Bernanke, Ben S., Michael T. Kiley, and John M. Roberts. 2019. “Monetary Policy Strategies for a Low-Rate Environment.” AEA Papers & Proceedings 109, pp. 421–426.

Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System. 2012. “FOMC Projections materials, accessible version.” January 25.

Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System. 2019a. “Financial Stability Report.” May.

Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System. 2019b. “FOMC Projections materials, accessible version.” June 19.

Cascio, Elizabeth U., and Ayushi Narayan. 2019. “Who Needs a Fracking Education? The Educational Response to Low-Skill Biased Technological Change.” NBER Working Paper 21359 (revised).

Charles, Kerwin Kofi, Erik Hurst, and Matthew J. Notowidigdo. 2018. “Housing Booms and Busts, Labor Market Opportunities, and College Attendance.” American Economic Review 108(10), pp. 2,947–2,994.

Christensen, Jens H. E., Glenn D. Rudebusch. 2019. “A New Normal for Interest Rates? Evidence from Inflation-Indexed Debt.” FRB San Francisco Working Paper 2017-07 (revised), forthcoming in The Review of Economics and Statistics.

Congressional Budget Office. Various years. “Budget and Economic Data: Potential GDP and Underlying Inputs.” Report.

Crump, Richard K., Stefano Eusepi, Marc Giannoni, and Ayşegül Şahin. 2019. “A Unified Approach to Measuring u*.” BPEA Conference Draft, March 7–8. Forthcoming in Brookings Papers on Economic Activity.

Davis, Steven J., Jason R. Faberman, and John C. Haltiwanger. 2013. “The Establishment-Level Behavior of Vacancies and Hiring.” The Quarterly Journal of Economics 128(2), pp. 581–622.

Federal Reserve Bank of New York. 2019. “Measuring the Natural Rate of Interest.” Accessed August 29, 2019.

Holston, Kathryn, Thomas Laubach, and John C. Williams. 2017. “Measuring the Natural Rate of Interest: International Trends and Determinants.” Journal of International Economics 108, supplement 1 (May), pp. S39–S75.

International Monetary Fund. 2013. “The Dog That Didn’t Bark: Has Inflation Been Muzzled or Has It Just Been Sleeping?” Chapter 3 in World Economic Outlook: Hopes, Realities, and Risks (April), pp. 29–95.

Jacob, Punnoose, and Martin Wong. 2018. “Estimating the NAIRU and the Natural Rate of Unemployment for New Zealand.” Reserve Bank of New Zealand Analytical Notes AN2018/04, March.

Jordà, Òscar, Chitra Marti, Fernanda Nechio, and Eric Tallman. 2019. “Inflation: Stress-Testing the Phillips Curve.” FRBSF Economic Letter 2019-05 (February 11).

Lansing, Kevin J. 2018. “Endogenous Regime Switching Near the Zero Lower Bound.” FRB San Francisco Working Paper 2017-24 (revised).

Laubach, Thomas, and John C. Williams. 2003. “Measuring the Natural Rate of Interest.” Review of Economics and Statistics 85(4, November), pp. 1,063–1,070.

Leduc, Sylvain, and Zheng Liu. 2019. “The Weak Job Recovery in a Macro Model of Search and Recruiting Intensity.” FRB San Francisco Working Paper 2016-09 (revised). Forthcoming in American Economic Journal: Macroeconomics.

Mertens, Thomas M., and John C. Williams. 2019. “Monetary Policy Frameworks and the Effective Lower Bound on Interest Rates.” FRB San Francisco Working Paper 2019-01 (revised June).

Modestino, Alicia S., Daniel Shoag, and Joshua Ballance. 2016. “Downskilling: Changes in Employer Skill Requirements over the Business Cycle.” Labour Economics 41, pp. 333–347.

Nechio, Fernanda. 2015. “Have Long-Term Inflation Expectations Declined?” FRBSF Economic Letter 2015-11 (April 6).

Nessén, Marianne, and David Vestin. 2005. “Average Inflation Targeting.” Journal of Money, Credit, and Banking 37(5), pp. 837–863.

Okun, Arthur M. 1973. “Upward Mobility in a High-Pressure Economy.” Brookings Papers on Economic Activity 1973(1), pp. 207–261.

Petrosky-Nadeau, Nicolas, and Robert G. Valletta. 2019. “Unemployment: Lower for Longer?” FRBSF Economic Letter 2019-21 (August 19).

Powell, Jerome H. 2019. “Economic Outlook and Monetary Policy Review.” Speech to the Council on Foreign Relations, New York, NY. June 25.

Svensson, Lars E.O. 1999. “Price-Level Targeting versus Inflation Targeting: A Free Lunch?” Journal of Money, Credit, and Banking 31(3), pp. 277–295.

Opinions expressed in FRBSF Economic Letter do not necessarily reflect the views of the management of the Federal Reserve Bank of San Francisco or of the Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System. This publication is edited by Anita Todd and Karen Barnes. Permission to reprint portions of articles or whole articles must be obtained in writing. Please send editorial comments and requests for reprint permission to research.library@sf.frb.org