Workers with a college degree typically earn substantially more than workers with less education. This so-called college wage premium increased for several decades, but it has been flat to down in recent years and declined notably since the pandemic. Analysis indicates that this reflects an acceleration of wage gains for high school graduates rather than a slowdown for college graduates. This pattern is most evident for workers in racial and ethnic groups other than White, possibly reflecting an unusually tight labor market that may have altered their college attendance decisions.

College graduates on average earn much higher wages than workers without a college degree. Because this higher earning potential lasts throughout a typical working life, the decision of whether or not to attend college has long-lasting consequences that extend well beyond labor market conditions when the decision is made. For most people considering college, the implied increase in lifetime earnings outweighs the cost enough to make college a sound financial investment, often with very high returns (Daly and Bengali 2014). This makes college education an important source of upward socioeconomic mobility within and across generations. As such, college is an important determinant of financial well-being, with varying impacts for different groups, for example those defined by race and ethnicity.

In this Economic Letter, we examine the evolving patterns in the college wage premium over time and across groups, updating and extending prior work on the topic (Valletta 2019). We examine recent patterns in how the overall wage gap between college graduates and high school graduates differs for workers across four broad racial and ethnic groups that account for most of the U.S. population: White, Black, Hispanic, and Asian including Pacific Islander. Our estimates show that, across all groups, the wage gap peaked in the mid-2010s but later declined a small but notable 4 percentage points to about 75% in 2022. This recent decline in the college wage premium has been most evident for groups other than White workers. Additional breakdowns suggest that the decline in recent years is attributable to more rapid wage gains for high school graduates rather than slower wage gains for college graduates. We interpret these patterns, highlighting the impact tight labor markets could have on people’s decisions of whether or not to attend college.

The college wage premium over time

The college wage premium is typically defined as the percentage difference between average wages earned by workers with a four-year college degree and those by workers with a high school diploma. Although wages differ substantially among individuals within the broad college and high school groups, we focus on this overall comparison because it can provide useful insights about the decision to attend college and its economic implications.

For our analysis, we use microdata from the Current Population Survey (CPS), the U.S. government survey that gathers information on about 60,000 households each month and is the basis for official statistics on the U.S. labor force. We focus on the sample of one-fourth of survey respondents who are asked each month about their wages and hours; we combine these responses over the 12 months of each year to yield large annual samples that are suitable for reliable comparisons across racial and ethnic groups.

These data allow us to assess patterns in the college wage premium, using standard statistical regressions to adjust the results for differences in the demographic and geographic composition of the sample across groups and over time. Valletta (2019) provides additional details on the methodology; as in that paper and other recent work (Autor et al. 2023), we exclude from our analysis respondents whose wages are not directly reported but instead are assigned by the survey administrators based on other characteristics. For our comparisons based on race and ethnicity, we define the groups in a mutually exclusive way, with no overlap: individuals who self-identify as Hispanic ethnicity are treated as such in our analysis unless their self-identified race is Black. We analyze data through the full year of 2022.

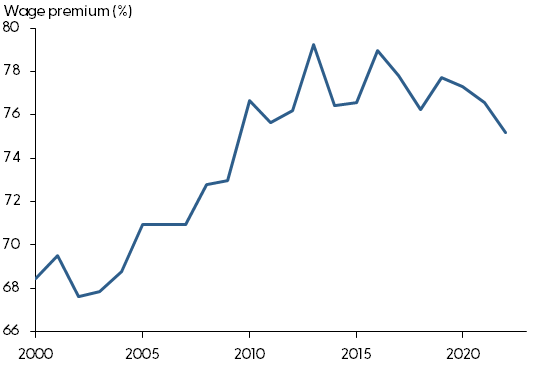

The results in Figure 1 show this estimated wage premium since 2000, expressed as percentages. For example, the figure shows that in 2000, wages for workers with at least a college degree were about 68% higher on average than wages earned by high school graduates. Our results extend and are in line with earlier work, which found that the wage premium rose substantially during the three decades starting in the 1980s but flattened out during the decade following the Great Recession of 2007–09 (Valletta 2019, Ashworth and Ransom 2019). With data for the three years since the COVID-19 pandemic began in 2020 included, the college wage premium has declined slightly, from a peak of about 79% in the mid-2010s to about 75% in 2022. This drop of 4 percentage points may seem small, but it is meaningful by comparison with the gain of about 10 percentage points in the years between 2000 and the mid-2010s.

Figure 1

Overall college wage premium

Source: Authors’ calculations from CPS earnings records.

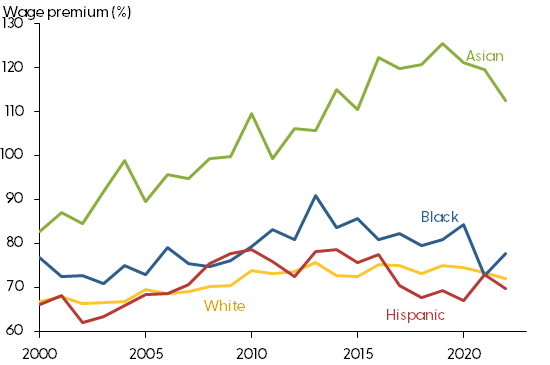

The overall pattern masks substantial variation across our four racial and ethnic groups. Figure 2 shows that the college wage premium is especially large for Asian workers, with college graduates earning more than twice what high school graduates earn. This reflects about a 120% premium, compared with about a 70–80% premium for the other three racial/ethnic groups. The college wage gap is also somewhat larger for Black workers than for Hispanic and White workers, although the premiums for those groups have largely converged in recent years. The higher college premium for Asian workers likely reflects differences in their choice of college majors, attainment of post-graduate degrees, and subsequent occupations.

Figure 2

College wage premium by race and ethnicity

Source: Authors’ calculations from CPS earnings records.

All four groups saw gains through at least the early part of the recovery from the 2007–09 recession. While the premium continued to rise for Asian workers, the premium flattened for White workers in the latter half of the recovery and fell for Hispanic and Black workers. Moreover, since the 2020 pandemic recession, the college wage premium edged down slightly for all groups except Hispanic workers.

The role of high school graduates’ wages in the college wage premium

Why did the college wage premium plateau and begin to decline? The change could reflect rising wages for high school graduates, falling wages for workers with a college degree, or a combination of the two. Both the latter half of the recovery from the 2007–09 recession and the labor market rebound after the 2020 pandemic recession were characterized by historically tight labor markets. Moreover, research indicates that tight labor markets during these two periods strengthened employment and earnings outcomes for lower wage and economically disadvantaged workers, such as certain racial/ethnic groups and those with only a high school education, compared with more advantaged groups, such as college graduates (Aaronson et al. 2019, Autor, Dube, and McGrew 2023). Together, these observations suggest that rising relative wages of high school graduates may help explain the reductions in the college wage gap.

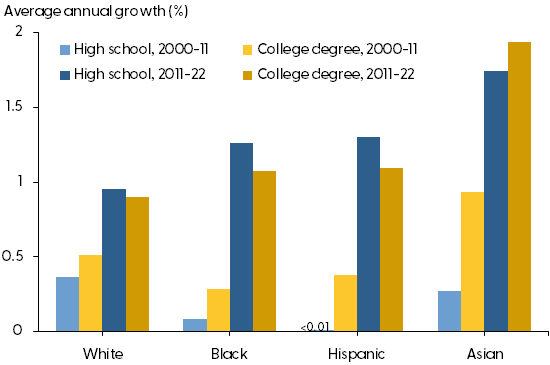

Figure 3 compares wage growth by educational attainment for our four racial/ethnic groups. For consistency with typical assessments of wage growth, we adjust wages for overall inflation. To highlight key trends, the figure shows compound annual wage growth rates from 2000 to 2011 and from 2011 to 2022. We split the sample in 2011 because wage patterns shifted around that year.

Figure 3

Real wage growth by race/ethnicity and education

Source: Authors’ calculations from CPS earnings records, deflated by the personal consumption expenditures price index.

The patterns in Figure 3 provide some support for the idea that the flattening and reversal in the college wage premium in recent years is explained primarily by faster wage growth for high school graduates rather than slower wage growth for college graduates. From 2000 to 2011, real wages grew slowly for all groups, about 0.5 percentage point or less annually, with the exception of notably more rapid growth for Asian college graduates. Since 2011, growth in real wages has picked up for all groups. However, wage growth accelerated more for high school graduates than for college graduates. This pattern is particularly pronounced for Black and Hispanic workers. For both groups, wages for high school graduates grew slightly faster than wages for college graduates, a notable reversal of the pattern of faster wage growth for college graduates before 2011. By contrast, since 2011 wages for White high school graduates and college-educated workers rose roughly the same amount, while wages for Asian college graduates rose more rapidly than those for Asian high school graduates. These patterns are consistent with the flat college wage gap for White workers and the rising gap for Asian workers over this period in Figure 2.

Although not shown in Figure 3, the pattern for Asian workers shifted during the pandemic. Real wages for Asian high school graduates picked up substantially and have risen more than for Asian college graduates since 2020. This underlies the drop in the college wage premium for this group after 2019, following substantial increases in prior years (Figure 2).

Discussion

Our analysis in this Letter indicates that the college wage premium stopped growing during the recovery from the 2007–09 recession, with an outright decline evident in recent years. We also explored variation in the levels and trends in college premiums across racial and ethnic groups. Notably, the decline in the college wage premium has been especially pronounced for Black and Hispanic workers, although it also occurred for Asian workers during the pandemic period of 2020–22. We find evidence that more rapid wage growth for high school graduates, rather than slower wage growth for college graduates, is the primary reason for the flattening or reduction of the college wage premium.

Our findings suggest that historically tight labor markets in recent years have changed relative wages, possibly altering the perceived benefits of a college education. The decision to attend college affects people’s lifetime earnings and hence transcends near-term labor market conditions. For example, recent research demonstrates that the college wage premium approximately doubles over the typical individual’s work life (Deming 2023). As such, focusing narrowly on short-term labor market incentives may distort people’s decisions of whether or not to attend college. This may be an important consideration given that the college wage premium has declined in recent years, particularly for workers in racial and ethnic groups other than White.

Regional Policy Economist, Economic Research Department, Federal Reserve Bank of San Francisco

Marcus Sander

Research Associate, Economic Research Department, Federal Reserve Bank of San Francisco

Senior Vice President and Associate Director of Research, Economic Research Department, Federal Reserve Bank of San Francisco

Cindy Zhao

Research Associate, Economic Research Department, Federal Reserve Bank of San Francisco

References

Aaronson, Stephanie R., Mary C. Daly, William L. Wascher, and David W. Wilcox. 2019. “Okun Revisited: Who Benefits Most from a Strong Economy?” Brookings Papers on Economic Activity 2019(1), pp. 333–404.

Ashworth, Jared, and Tyler Ransom. 2019. “Has the College Wage Premium Continued to Rise? Evidence from Multiple U.S. Surveys.” Economics of Education Review 69, pp. 149–154.

Autor, David, Arindrajit Dube, and Annie McGrew. 2023. “The Unexpected Compression: Competition at Work in the Low Wage Labor Market.” NBER Working Paper 31010 (March).

Daly, Mary C., and Leila Bengali. 2014. “Is It Still Worth Going to College?” FRBSF Economic Letter 2014-13, May 5.

Deming, David J. 2023. “Why Do Wages Grow Faster for Educated Workers?” NBER Working Paper 31373 (June).

Valletta, Robert G. 2019. “Recent Flattening in the Higher Education Wage Premium: Polarization, Skill Downgrading, or Both?” In Education, Skills, and Technical Change: Implications for Future U.S. GDP Growth, eds. Charles Hulten and Valerie Ramey, NBER-CRIW conference volume 313-3. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Opinions expressed in FRBSF Economic Letter do not necessarily reflect the views of the management of the Federal Reserve Bank of San Francisco or of the Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System. This publication is edited by Anita Todd and Karen Barnes. Permission to reprint portions of articles or whole articles must be obtained in writing. Please send editorial comments and requests for reprint permission to research.library@sf.frb.org