New evidence based on listings of homes for sale from 2000 to 2019 suggests house prices adjust to monetary policy changes over weeks rather than years, faster than previously thought. Housing list prices fall within two weeks after the Federal Reserve announces an unexpected policy tightening, similar to responses of other financial assets. House prices respond more strongly to unexpected changes in long-term interest rates than to surprises in the short-term federal funds rate. Changes in mortgage rates following Fed announcements are key to explaining this rapid house price reaction.

The large role of the housing market in the U.S. economy makes it an important consideration for policymakers. For instance, residential investment and spending on housing services together accounted for 16% of U.S. GDP in the third quarter of 2022. However, unlike other financial assets that adjust rapidly to interest rate changes, past research found that house price growth is gradual and appears to be insensitive to changes in interest rates (Case and Shiller 1989). Summarizing that research, Kuttner (2013) observed that, while housing prices do adjust to monetary policy, these impacts materialize slowly, after around two years.

In this Economic Letter, we revisit the question of how long it takes for house prices to respond to monetary policy shocks. The analysis is based on our work in Gorea, Kryvtsov, and Kudlyak (2022), studying the effects of unanticipated changes in monetary policy on housing prices. We find that monetary policy surprises affect house prices far more quickly than commonly thought. Monetary policy impacts housing prices through list prices—the prices of properties for sale posted by sellers—within a matter of weeks instead of years. The response is driven largely by unanticipated policy changes to forward guidance and large-scale asset purchases. We find that these kinds of monetary policy changes increase interest rates for long-term mortgages. As mortgage rates increase, it becomes more expensive to buy a house at a given list price for buyers needing to finance the purchase. In response, sellers lower their list prices to be able to sell the property.

Measuring local house prices

We use data on home listings and sales from the CoreLogic Multiple Listing Service (MLS). The data contain detailed information on all housing units listed for sale on MLS platforms in the United States. This allows us to construct high-frequency zip code-specific indexes of both list and sales prices, whereas traditional house price indexes focus on final sales prices at monthly or quarterly frequency.

We focus on listings of single-family homes and apartments. Our sample includes over 92 million listings from 2001 to 2019. Each listing contains information on the list price, sale price, listing and sale dates, and characteristics of the property, such as the number of bedrooms and square feet of living space. For each zip code, we construct weekly indexes of list prices and sales prices for our sample period. The indexes reflect prices within each zip code after accounting for seasonal factors and any changes in the composition of houses in terms of their characteristics.

What are monetary policy shocks?

To identify the effect of monetary policy on house prices, we need a measure of monetary policy changes that are unexpected, so-called shocks. Changes in expectations about future interest rates represent information shocks that affect the market value of all interest-sensitive assets, including houses. A contractionary shock is one that leads people to expect higher interest rates now or in the future, causing economic growth to slow or reverse. Generally, this happens when the Federal Reserve unexpectedly raises the target for its short-term policy interest rate, known as the federal funds rate. This unexpected change tends to spill over into higher rates for loans, including mortgage loans, making them more expensive and potentially slowing down home purchasing. An expansionary shock is one that creates expectations for lower interest rates and causes the economy to grow.

In our analysis, we use the estimated monetary policy shocks from Swanson (2021), which reflect three types of monetary policy surprises. The first type is a shock to the federal funds rate, which happens when the Fed unexpectedly raises or lowers its target range. The federal funds rate historically has been the Fed’s primary policy lever. The second type of surprise is unexpected changes to the Fed’s communication about its plans for future interest rates, known as forward guidance. The third type of monetary policy surprise is related to the Fed’s large-scale asset purchases. Swanson (2021) measures these three monetary policy surprises by tracking market prices for certain financial assets that change immediately after the Fed’s monetary policy announcements.

How monetary policy surprises affect house prices

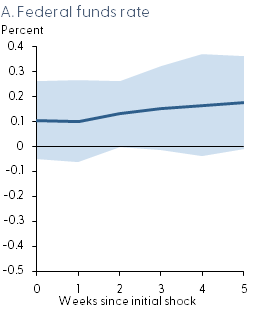

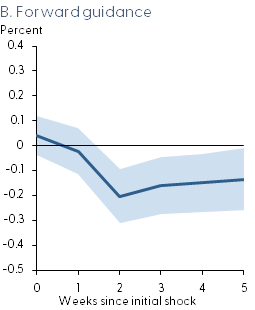

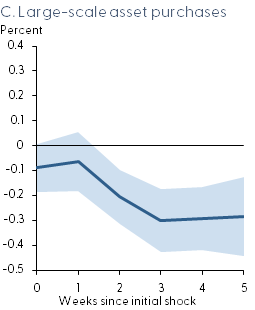

We estimate the response of house prices to monetary policy using a local projections method, a statistical tool proposed by Jordá (2005), which allows us to isolate the effect of shocks on the economic series of interest. Using this method, we trace out how house prices change in the weeks following a monetary policy action that brings about an unanticipated change in the federal funds rate, the Fed’s forward guidance, or the Fed’s large-scale asset purchases. The method also considers how monetary policy shocks interact with other economic conditions, including previous house price changes, and how the response differs across narrow areas (defined by zip codes). Figure 1 shows the estimated response of house prices to the three types of contractionary monetary policy shocks of a typical size, measured as a one standard deviation shock over our 2001–19 sample period.

Figure 1

Responses of housing list prices to three contractionary monetary policy surprises

Note: Responses to a one-standard-deviation contractionary shock; shading reflects a 90% confidence interval.

Panel A shows that the surprise in the federal funds rate—a short-term interest rate change—appears to have little effect on listed house prices. However, we find that housing list prices respond much more quickly than previously thought to unexpected changes in long-term interest rates. Panel B shows that a one standard deviation contractionary shock to forward guidance, which is typically associated with an increase in two-year Treasury rates of 4.6 basis points (0.046 percentage point), causes a 0.2% drop in house prices. A one standard deviation shock to large-scale asset purchases (panel C), which usually moves 10-year Treasury rates 5.4 basis points (0.054 percentage point), causes a larger and more protracted drop in house prices of 0.3%. These responses are large and surprising, considering that these shocks do not reflect immediate changes in short-term interest rates. The housing list price adjustments that we uncover occur within two weeks after monetary policy announcements, which is much faster than the two years found in past research.

The responses in panels B and C are similar in size to responses of financial assets on the day of a Federal Open Market Committee announcement, derived using the same surprise measures (see, for example, Tables 5 and 6 in Swanson 2021). The key difference is that financial assets tend to respond strongly on the day of the monetary policy announcement, and those responses tend to be larger for shocks to the federal funds rate than to forward guidance or large-scale asset purchases. For example, Swanson (2021) reports that the Standard & Poor’s 500 stock price index responds by –0.37% following a federal funds rate shock, compared with –0.14% for forward guidance shocks and 0.03% for large-scale asset purchase shocks.

How do monetary policy shocks flow through to house prices?

We next explore a channel through which monetary policy shocks affect house prices. When people buy homes in the United States, they usually take out a mortgage to pay off their home purchase over time. When the Fed raises interest rates, it raises the floor on interest rates paid on all loans in the economy, including mortgages. When mortgage rates rise, potential homebuyers face larger payments for the same house, increasing its annual and total cost for borrowers. Consequently, sellers might decide to lower their listing price if they worry that they will be unable to sell the property because buyers can no longer afford the increased cost of a mortgage. In this way, a tightening of monetary policy could cause list prices to fall.

To test this hypothesis, we examine how mortgage rates change in response to monetary policy shocks. We use data on 30-year fixed-rate mortgages from the Primary Mortgage Market Survey. We find that mortgage rates respond quickly and significantly to monetary policy surprises related to forward guidance and large-scale asset purchases. However, mortgage rates do not respond similarly to federal funds rate surprises, likely because mortgage rates are longer-term rates by design.

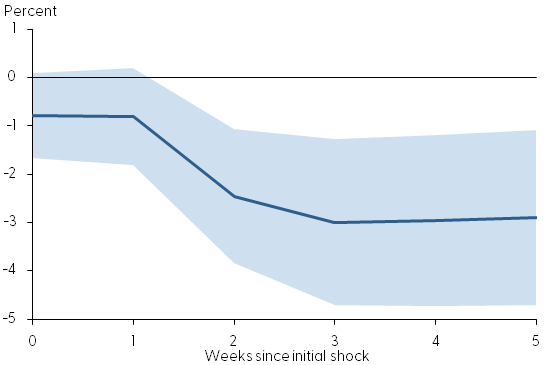

We next examine how much these monetary policy-driven changes in mortgage rates affect house prices. We find that a 1 percentage point increase in the mortgage rate generated by a monetary policy shock is associated with house prices falling immediately by 1% (Figure 2). Prices continue declining in the weeks following a monetary policy announcement and ultimately settle 3% lower three weeks after the shock.

Figure 2

Response of list prices to change in mortgage rates

Note: Responses to a one-standard-deviation contractionary shock; shading reflects a 90% confidence interval.

Conclusion

In this Letter, we show that house list prices respond to monetary policy surprises in a matter of weeks; this is contrary to the established research that suggests house prices take years to adjust. We find that short-term changes such as shocks to the federal funds rate have less of an impact than surprises to forward guidance and large-scale asset purchases, both of which affect long-term interest rates. This effect of monetary policy on housing prices occurs via changes in mortgage rates. When mortgage rates increase, list prices tend to decrease due to the higher total cost of owning a home. Our results on the rapid response of house prices to unexpected changes in monetary policy provide direct evidence regarding the speed of house price adjustments, which may help policymakers better anticipate the effects of policy actions.

Denis Gorea

Economist, European Investment Bank

Oleksiy Kryvtsov

Senior Research Officer, Bank of Canada

Augustus Kmetz

Research Associate, Economic Research Department, Federal Reserve Bank of San Francisco

Marianna Kudlyak

Research Advisor, Economic Research Department, Federal Reserve Bank of San Francisco

Mitchell Ochse

Economist, Bureau of Labor Statistics

References

Case, Karl E., and Robert J. Shiller. 1989. “The Efficiency of the Market for Single-Family Homes.” American Economic Review 79(1), pp. 125–137.

Gorea, Denis, Oleksiy Kryvtsov, and Marianna Kudlyak. 2022. “House Price Responses to Monetary Policy Surprises: Evidence from the U.S. Listings Data.” FRB San Francisco Working Paper 2022-16.

Jordà, Òscar. 2005. “Estimation and Inference of Impulse Responses by Local Projections.” American Economic Review 95(1), pp. 161-182.

Kuttner, Kenneth N. 2013. “Low Interest Rates and Housing Bubbles: Still No Smoking Gun.” Chapter 8 in The Role of Central Banks in Financial Stability: How Has It Changed?, eds. Douglas D. Evanoff, Cornelia Holthausen, George G. Kaufman, and Manfred Kremer. World Scientific Publishing Co. Pte. Ltd., pp. 159–185.

Swanson, Eric T. 2021. “Measuring the Effects of Federal Reserve Forward Guidance and Asset Purchases on Financial Markets.” Journal of Monetary Economics 118, pp. 32–53.

Opinions expressed in FRBSF Economic Letter do not necessarily reflect the views of the management of the Federal Reserve Bank of San Francisco or of the Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System. This publication is edited by Anita Todd and Karen Barnes. Permission to reprint portions of articles or whole articles must be obtained in writing. Please send editorial comments and requests for reprint permission to research.library@sf.frb.org