Indeed, in December 2012, The Federal Open Market Committee (FOMC) announced numerical thresholds for the unemployment rate and inflation that will guide future policy decisions about the federal funds rate.

What Are the Numerical Thresholds?

The FOMC statement of December 2012 read (emphasis is added by me):

“To support continued progress toward maximum employment and price stability, the Committee expects that a highly accommodative stance of monetary policy will remain appropriate for a considerable time after the asset purchase program ends and the economic recovery strengthens. In particular, the Committee decided to keep the target range for the federal funds rate at 0 to 1/4 percent and currently anticipates that this exceptionally low range for the federal funds rate will be appropriate at least as long as the unemployment rate remains above 6-1/2 percent, inflation between one and two years ahead is projected to be no more than a half percentage point above the Committee’s 2 percent longer-run goal, and longer-term inflation expectations continue to be well anchored.”

To answer your first question, these thresholds apply to federal funds rate guidance only.1 They are not considered signals for ending the third round of large-scale asset purchases, frequently called QE3, which I will discuss shortly.

Also, the criteria are thresholds, not triggers for action. That is, reaching one of the thresholds does not mean the Committee will immediately begin raising the federal funds rate target.

This communication shines the spotlight on the unemployment rate. It is important to clarify that the 6.5% threshold is not the Committee’s longer-term objective for unemployment. In fact, the FOMC doesn’t have a specific numerical goal for the unemployment rate (as the maximum level of employment is largely determined by factors outside of the purview of a central bank2). However, FOMC participants do provide their estimates for the longer-run unemployment rate. For example, the minutes from the March 20, 2013 FOMC meeting show that the central tendency for those estimates was 5.2 to 6.0%.3 The 6.5% threshold mentioned in the FOMC statement is above this range because monetary policy affects the economy with a lag, meaning that it takes some time for policymakers’ actions to affect the economy.

Needless to say, the unemployment rate doesn’t capture the full picture of labor market conditions on its own. For instance, a decline in the unemployment rate is not necessarily a sign of strength in the labor market. The unemployment rate can temporarily decline when job seekers become discouraged and give up actively seeking employment, and thus are not included in the Bureau of Labor Statistics’ measure of the labor force.4 Thus, to gain a more balanced picture of the labor market health, policymakers look at a range of labor market indicators, such as changes in employment and hours worked.

With respect to the inflation threshold, it is expressed in terms of projected inflation one to two years in the future, rather than current inflation. This shows that the Committee focuses on the underlying inflation trend, rather than on transitory inflation fluctuations. Again, remember that it can take a fairly long time for a monetary policy action to affect the economy and inflation, so the Committee’s threshold has to account for this lag.

What are the pros and cons of using numerical thresholds?

Most of the FOMC participants favored replacing the calendar-based guidance that they had used between August 2011 and December 2012 with the numerical thresholds.5 By moving from stating for how long they expected a policy to be in place to providing numerical thresholds, the Committee aimed to clarify its future behavior. In turn, they hoped this would allow market expectations of future policy actions to adjust automatically when economic conditions change.

Introducing numerical thresholds has some potential disadvantages. Markets could misinterpret them as being the Committee’s longer-run objectives or as triggers for immediate increases in short-term rates. However, these risks can be mitigated through various FOMC communications, such as the Chairman’s press conference or FOMC members’ speeches.

When does the FOMC expect to begin increasing the federal funds rate?

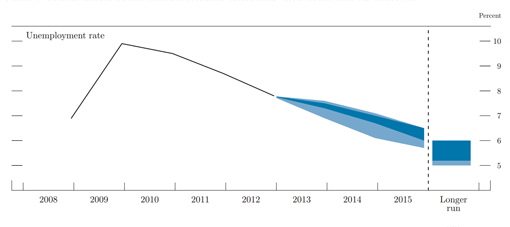

Now that we have discussed the numerical thresholds a bit, you might be wondering when the FOMC expects to begin raising the federal funds rate. Let’s turn to the Economic Projections from Federal Reserve Board members and Federal Reserve Bank Presidents, which are released quarterly. These contain forecasts from FOMC meeting participants over a three-year horizon for inflation, unemployment, real GDP, and the federal funds rate. According to the most recent projections available at the time of this response (March 2013 – pdf), most FOMC meeting attendees do not expect the unemployment rate to reach the 6.5% threshold until 2015. The central tendency of the projections for the unemployment rate ranges from 7.3 to 7.5% at of the end of 2013, 6.7 to 7.0% at the end of 2014, and 6.0 to 6.5% at the end of 2015. Unemployment rate projections in Figure 1 show the central tendency as darker blue and the full range of projections as lighter blue.

Figure 1. Unemployment Rate Projections of Federal Reserve Board Members and Federal Reserve Bank Presidents, March 2013.

Source: http://www.federalreserve.gov/monetarypolicy/files/fomcprojtabl20130320.pdf

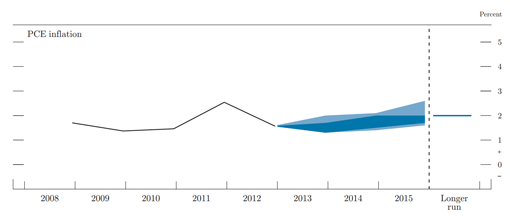

At that meeting, most attendees expected inflation to remain at or below the FOMC’s target of 2% (see Figure 2).

Figure 2. Inflation Projections of Federal Reserve Board Members and Federal Reserve Bank Presidents, March 2013.

Source: http://www.federalreserve.gov/monetarypolicy/files/fomcprojtabl20130320.pdf

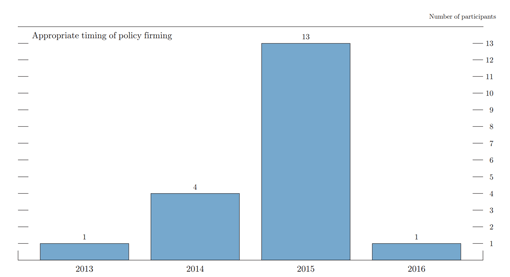

These two projections—elevated unemployment and subdued inflation over the next three years—suggest that most meeting attendees anticipate the federal funds rate will remain exceptionally low until 2015, given the information available as of March 2013. Indeed, as you can see from Figure 3, most believe that the initial increase in the target federal funds rate should occur sometime in 2015.

Figure 3. Overview of FOMC participants’ assessments of appropriate monetary policy, March 2013

Source: http://www.federalreserve.gov/monetarypolicy/files/fomcprojtabl20130320.pdf

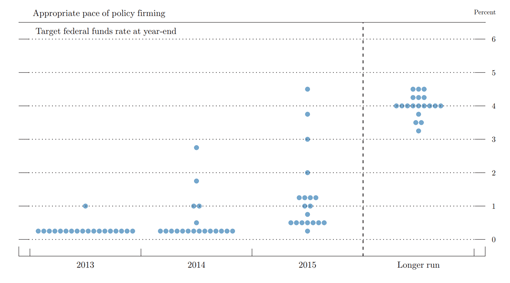

Figure 4 shows the FOMC meeting participants’ projections of the federal funds rate by year-end.

Figure 4. Appropriate Timing of Policy Firming, March 2013.

Source: http://www.federalreserve.gov/monetarypolicy/files/fomcprojtabl20130320.pdf

The median year-end 2015 projection for the appropriate federal funds rate target is 1%, which implies a cumulative increase of 0.75% over the course of 2015. If we assume that the federal funds rate would increase by increments of at least 0.25 percentage points at a time, the median projected value for the federal funds rate would be consistent with one to three increases in the target rate by the end of 2015.

What about QE3?

The Fed has also given some qualitative guidance for when it might begin to end QE3. The FOMC statement from March 20, 2013, states that the Committee will continue to purchase assets until the labor market outlook improves substantially, and they will take into account the costs and benefits of QE3 (emphasis added by me):

The Committee will continue its purchases of Treasury and agency mortgage-backed securities, and employ its other policy tools as appropriate, until the outlook for the labor market has improved substantially in a context of price stability. In determining the size, pace, and composition of its asset purchases, the Committee will continue to take appropriate account of the likely efficacy and costs of such purchases as well as the extent of progress toward its economic objectives.

There remains ambiguity on what constitutes substantial improvement in the labor market and there seems to be some disagreement among FOMC participants with respect to the costs and benefits of QE3. However, as of March 20, 2013 most of the Committee members view benefits as exceeding the costs and do not believe that labor market improvement have been substantial enough to warrant changes.6

For additional information on individual FOMC participant’s perspectives on these policies, please see:

December 12, 2012 Chairman’s Press Conference

Speeches of Federal Reserve Officials (Board of Governors)

Speeches of Reserve Bank presidents

Date of publication: Second Quarter 2013

End Notes

1. This discussion borrows heavily from Chairman Bernanke’s press conference after the release of this December 12, 2012 FOMC statement.

2. The Committee releases its estimate of the longer-run normal rate of unemployment in its quarterly Economic Projections. The Committee recognizes that such assessments are necessarily uncertain and subject to revision. You can find the FOMC’s estimates of longer-run normal rates of output growth and unemployment in the FOMC’s “Statement of Economic Projections.”

3. The central tendency excludes the three highest and three lowest projections for each variable in each year.

4. Please visit the Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS) website to learn more about how statistics about the unemployed are collected.

5. See the minutes of the December 2012 FOMC meeting.

6. See also Chairman Bernanke’s Semiannual Monetary Policy Report to the Congress of February 26, 2013, for additional discussion of costs and benefits of accommodative monetary policy.