Remarks as prepared for delivery.

Good morning. Thank you, Laura for that kind introduction. And thank you to all of you in the audience who do such important work for families, communities, and the economy. It is my distinct honor to be here and I look forward to our conversation.

But before we turn to our dialogue, I thought I would offer some opening remarks.

No matter where I go or who I talk to these days, I hear a similar refrain: “housing, will it get better?” Concerns span generations, geographies, income levels, and all races and ethnicities.1 Indeed, according to a recent poll by the Cato Institute, 87 percent of Americans worry about the cost of housing, and nearly 70 percent worry their kids and grandkids won’t be able to buy a home.2

Affordable housing shortages are not new. What’s different today is how many people are affected—a large and growing number, more than at any other time in our living history.

You don’t have to go too far to see this. As people regularly in the field, this is your day to day. In our travels at the San Francisco Fed, we find it everywhere. In communities that have struggled for decades, like urban centers and rural areas, to ones newer to the issues like Boise, Idaho, Salt Lake City, Phoenix, Las Vegas, the list goes on.

This culminates in the sentiment that housing is broken. That it’s falling short of our collective expectations, not only to provide shelter, but also to support growth, community, and an economy that works for all.

Today, I will discuss how we got here, and what it will take to change the equation. My message is clear: collective problems require collective efforts, and it will take all of us—community development, nonprofits, government, and business—working together to achieve greater access to housing.

But before I get started, let me remind you that the remarks I make today are mine and do not necessarily reflect the views of anyone else in the Federal Reserve System.

Long-standing, Worse Now

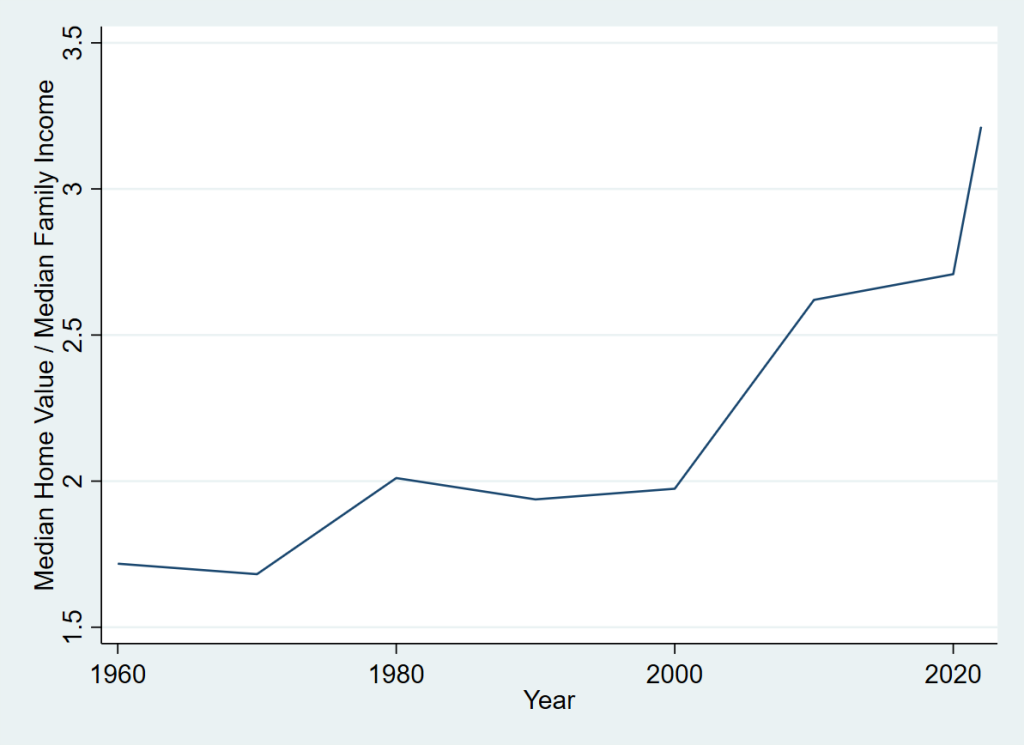

So, why are so many Americans worried about housing costs? The affordability data tell the story. The figure (Figure 1) shows median home values relative to median family income for the past six decades. This calculation allows us to track affordability without undue influence of interest rates or business cycles.

Figure 1

Housing affordability over time

By this measure, housing has become increasingly more expensive. In 1960, the typical home was worth about 1.7 times the median family’s income.3 By 2022, that ratio had risen to well over three. Almost double. While the affordability gap has been accumulating for 50 years, it’s widened considerably in the past 20.

Many things contribute to this decline in affordability, but one key variable is supply. Again, the data tell the story. The next figure (Figure 2) shows housing starts relative to the overall population.4 Focusing on the green line, which smooths through the year-to-year fluctuations in the series, housing supply has dropped precipitously since the 2008 financial crisis and now is near its recent historical low.

Figure 2

Housing supply over time

And this is the root of our problem. With so few homes available to meet demand, the value of homes has soared.

And this transmits through the economy. Limiting affordability not only for home buyers but for renters as well. The latest data show that about half of all renter households are experiencing a cost burden—spending more than 30 percent of their income on rent and utilities, a notable increase over previous years.5

Putting these facts together, it’s no wonder that so many Americans are talking about housing.6

Everyone’s Problem

But this is not a problem just for those who are looking for a home. Whether we know it or not, it affects our collective well-being. When people are stressed about their housing situation, their health and productivity suffer.7 It also affects their decision-making, about where to work, reside, and how to participate in their community.8, 9

This point was brought home to me during a visit to Orange County, California. I was meeting with a group of local restaurant owners. We were talking about the challenges of finding and keeping workers. When I asked about housing, the room changed. Everyone had stories of loss. Loss of longtime employees who couldn’t afford the ever-increasing commute distances, loss of interested applicants who departed when they found out the cost of housing, and loss of opportunities to serve their customers and grow their businesses due to lack of staff. To them, housing was failing, and no one was winning.

This story is not unique. I am sure each of you has heard many. Together, they remind us that housing is more than a basic need. It is an essential part of well-being, and well-being is an essential part of a thriving community and a healthy economy.10 If we miss on something so fundamental, everyone feels it, and we are collectively worse off.

Getting Our Housing in Order

So, what should we do?

As I said, collective problems call for collective solutions. So, we will all have to participate.

Let’s first start with what the Fed can do.

One lever that we and other regulatory agencies have is the CRA, which has brought you all together this week. The CRA has played a significant role in driving investment into low- and moderate-income communities, 11 and it is an important tool for ongoing housing solutions.

The Federal Reserve also contributes through our core monetary policy responsibilities, to create a stable and healthy economy with price stability and full employment.12 These goals were given to us by Congress and are the foundation of a sustainable economy that works for all.

As you know, we have been missing on our price stability mandate for the past two years. Rising housing costs have been a key driver of these misses, boosting inflation and worsening affordability.13 This burden has fallen especially harshly on those least able to afford it.14 That is why the Federal Reserve has been so focused and resolute on getting inflation down.

Of course, I recognize that higher interest rates also raise housing costs. But these adjustments are temporary and needed to bring down inflation. History has taught us that price stability is the single best mechanism to ensure sustainable growth. Without this condition, the economy, the labor market, and the housing market all falter. That is why we are committed to finishing the job.

Ultimately, however, the tools of the Fed are limited. We can create the economic conditions for housing, but our efforts will not be sufficient to rebalance the housing equation. This will require other important players in the economy.

Fortunately, many have already taken up the charge. Governments, businesses, and communities are recognizing the problems, forging partnerships, and creating solutions. Often taking on third rails of policy to do it.

Take governments. Many are tackling longstanding barriers to development, like land use rules, zoning laws, and planning policies.15 The idea is to change the way space is used, to allow for more housing, sometimes denser housing, and ultimately create greater affordability. States as diverse as Oregon, Maine, and Utah and cities like Minneapolis are engaged in activities like these.16

Businesses and business organizations are also actively working on housing, recognizing that to grow their businesses, employees need a secure place to live. In my home state of California, the Santa Rosa Metro Chamber of Commerce is partnering to finance the construction of more homes.17 And just down the road from here, in Donald, Oregon, GK Machine is building a housing development to support its manufacturing employees. Importantly, these efforts are not limited to coastal states or urban centers. In Spencer, Indiana, a town of roughly 2,500 people, a medical device manufacturer is building homes for employees.18 The point is, challenges are everywhere, and businesses are rising to meet the occasion.

Finally, there are communities, the ones you’ve been working with for decades. They’re expanding their partner networks and building alliances across a wide range of sectors including public, private, and nonprofit. With this new breadth of partners comes the potential for new scale.

We’re seeing this play out in places like Riverside County, California, where a largely agricultural community aims to build 10,000 new units of affordable housing over the next 10 years. They’re doing this through partnerships with many players, importantly led by community.19 Here in Portland, we already see an outcome of such efforts. Community partners joined forces to turn a blighted property with no future into a four-story, multifamily, affordable housing development.20 These are examples of collective efforts leading to solutions that scale to the problem.

I see the fact that governments, businesses, and communities are joining with all of you as the type of focus and scale we need to change the equation on housing. The problems have gotten bigger than any single action. And none of us will be as strong alone. Good work done independently is good. Good work done together is great.

Home Truths

In the end, what we are really talking about is not housing, it’s home.

The dignity people deserve is a place to call their own and the freedom to choose it. When these things are constrained, lives are affected.

A few years back, I was driving from Boise, Idaho, to Twin Falls. I pulled into a highway gas station and found myself in a conversation with a young couple moving across the state. They were ready, but not excited. They told me they had to move. They were expecting a new baby and could no longer afford to live where they had grown up. So, they were venturing away from home and family for more affordable housing.

They will likely make it. Forge a new path. But is this what we really want?

That’s the conversation we need to have about housing.

And you are the people to carry this forward.

Thank you.

Footnotes

1. Joint Center for Housing Studies (2023, 2024).

2. Ekins and Gygi (2022).

3. The source for this figure is decennial Census data for 1960-2000 and American Community Survey (ACS) data for 2010, 2020, and 2022. This plotted ratio of median home values relative to median family income provides a straightforward measure of overall national home affordability. The plot shows that home affordability is the worst it has been in at least 60 years.

4. See Bernstein et al. (2021) for an earlier version of this figure and related analysis.

5. Joint Center for Housing Studies (2024).

6. Ekins and Gygi (2022).

7. See Singh et al. (2019) regarding impacts of housing disadvantage on mental health, Pribesh and Downey (1999) regarding impact on schooling outcomes, and Collinson et al. (2024) regarding impacts of evictions.

8. See Blumenberg and Siddiq (2023) regarding impact on commuting decisions, Plantiga et al. (2013) regarding impact on location decisions.

9. See https://www.frbsf.org/research-and-insights/blog/beyond-the-numbers/2022/10/13/beyond-the-numbers-inflation-concerns-persist-in-federal-reserves-twelfth-district/ for San Francisco Fed example; http://clevelandfed.org/publications/multimedia-storytelling/storytelling-affordable-housing for Cleveland Fed example; https://fedcommunities.org/articles/housing/ for Federal Reserve System examples.

10. See, for example, Ramakrishnan, et al. (2021).

11. According to Federal Financial Institutions Examination Council (2023) data, CRA data from banks in 2022 reported more than $150 billion in community development lending and nearly $284.6 billion in small business lending. These figures do not reflect all mortgages issued by banks subject to CRA to low- and moderate-income households.

12. https://www.federalreserve.gov/aboutthefed.htm

13. House price indexes were growing at historically high rates but have since slowed with the increases in interest rates. See Kmetz, Louie, and Mondragon (2023).

14. Joint Center for Housing Studies (2024).

15. Addressing these barriers allows for greater density and aims to promote greater affordability. See Terner Center for Housing Innovation (2019) and Minot (2023) for local government examples of local land use policy reforms. See Manji et al. (2023) for a review of 144 state laws passed in 20 states over several decades to support housing production, whether by requiring jurisdictions to plan for new housing, setting state standards for local land use and planning policies, offering incentives to advance housing-related goals, and/or imposing penalties for failing to carry out housing-related obligations.

16. See State of Maine (2022) regarding Maine’s 2022 legislation and Treskon et al. (2023) regarding Oregon’s 2019 legislation. See Liang, Staveski, and Horowitz (2024) regarding Minneapolis’ land use reforms adopted in 2020. See Manji et al. (2023) regarding Utah’s 2019 legislation requiring cities to show how they will address moderate-income housing needs in their General Plans. The law also allows the state to withhold funds from its transportation grant programs if cities fail to do so.

17. Santa Rosa Metro Chamber of Commerce (2021).

18. Ludden and Peñaloza (2023).

19. In Riverside County, California, the Lift to Rise Housing Catalyst Fund has started to bring together capital from public, private, and nonprofit partners to create 10,000 additional units of affordable housing over the next four years.

20. The Las Adelitas project is the public investment in the Portland, Oregon, Cully community. In addition to units of affordable housing, the development includes a community space and a new outdoor plaza.

References

Bernstein, Jared, Jeffery Zhang, Ryan Cummings, and Matthew Maury. 2021. “Alleviating Supply Constraints in the Housing Market.” Council of Economic Advisers blog, September 1.

Blumenberg, Evelyn, and Fariba Siddiq. 2023. “Commute Distance and Jobs-Housing Fit.” Transportation 50 (June), pp. 869–891.

Cohen, Rachel M. 2024. “What If Public Housing Were for Everyone?” Vox, February 10.

Collinson, Robert, John Eric Humphries, Nicholas Mader, Davin Reed, Daniel Tannenbaum, and Winnie van Dijk. 2024. “Eviction and Poverty in American Cities.” Quarterly Journal of Economics 139(1, February), pp. 57–120.

Ekins, Emily, and Jordan Gygi. 2022. “Survey Report: Cato Institute 2022 Housing Affordability National Survey.” December 14.

Federal Financial Institutions Examination Council. 2023. “Findings from Analysis of Nationwide Summary Statistics for 2022 Community Reinvestment Act Data Fact Sheet.” Last modified December 20.

Joint Center for Housing Studies. 2023. State of the Nation’s Housing 2023. Report, Harvard University.

Joint Center for Housing Studies. 2024. America’s Rental Housing 2024. Report, Harvard University.

Kmetz, Augustus, Schuyler Louie, and John Mondragon. 2023. “Where Is Shelter Inflation Headed?” FRBSF Economic Letter 2023-19 (August 7).

Liang, Linlin, Adam Staveski, and Alex Horowitz. 2024. Minneapolis Land Use Reforms Offer a Blueprint for Housing Affordability. Report, Housing Policy Initiative, The Pew Charitable Trusts.

Local Housing Solutions. n.d. General Obligation Bonds for Affordable Housing. Housing Policy Library, website accessed March 4, 2024.

Ludden, Jennifer, and Marisa Peñaloza. 2023. “Would You Live Next to Co-Workers for the Right Price? This Company Is Betting Yes.” NPR Morning Edition, May 2.

Manji, Shazia, Truman Braslaw, Chae Kim, Elizabeth Kneebone, Carolina Reid, and Yonah Freemark. 2023. Incentivizing Housing Production: State Laws from Across the Country to Encourage or Require Municipal Action. Housing Crisis Research Collaborative report, Terner Center for Housing Innovation and Urban Institute.

Minott, Owen. 2023. Pioneering Zoning Reforms in Grand Rapids, MI. Report, Bipartisan Policy Center.

Plantinga, Andrew, Cécile Détang-Dessendre, Gary Hunt, and Virginie Piguet. 2013. “Housing Prices and Inter-Urban Migration.” Regional Science and Urban Economics 43(2, March), pp. 296-306.

Pribesh, Shana, and Douglas B. Downey. 1999. “Why Are Residential and School Moves Associated with Poor School Performance?” Demography 36(4, November), pp. 521–534.

Ramakrishnan, Kriti, Elizabeth Champion, Megan Gallagher, and Keith Fudge. 2021. Why Housing Mobility Matters for Upward Mobility: Evidence and Indicators for Practitioners and Policymakers. Research report, Urban Institute, January 12.

Santa Rosa Metro Chamber of Commerce. 2021. “Affordable Housing Partnership Announces First Three Developments to Build New Homes in Sonoma County.” March 25.

Singh, Ankur, Lyrian Daniel, Emma Baker, and Rebecca Bentley. 2019. “Housing Disadvantage and Poor Mental Health: A Systematic Review.” American Journal of Preventive Medicine 57(2), pp. 262–272.

State of Maine. 2022. “Governor Mills Signs Bills to Address Maine’s Housing Shortage.” Office of Governor Janet T. Mills newsroom, April 27.

Terner Center for Housing Innovation. 2019. Lessons in Land Use Reform: Best Practices for Successful Upzoning. Report, UC Berkeley (December 1).

Treskon, Mark, Jorge González-Hermoso, Noah McDaniel, and Dennis Su. 2023. Local and State Policies to Improve Access to Affordable Housing. Report, Urban Institute, August 21.

Williams, Mariden. 2021. “South Jordan City and Ivory Homes Partnership Yields City’s First Subsidized Workforce Housing Development.” South Jordan Journal, April 28.