Thank you. It’s great to be in Portland. If I can find time, I like nothing better than to savor a cup of the excellent coffee Portland is famous for and then head over to Powell’s to dig through the stacks.

Today I’m going to talk about how the economy is doing and where I see it heading. I’ll highlight areas of strength, such as housing, and also some areas that have been holding us back, such as fiscal policy. I’ll offer my forecasts for economic growth, the job market, and inflation. And I’ll explain what the Federal Reserve is doing to keep the recovery on track and move toward the goals Congress has set for us, namely maximum employment and price stability. I should note that my remarks represent my own views and not necessarily those of others in the Federal Reserve System.

Since there are a lot of CFOs here, let me go straight to the bottom line: The economy has been improving for nearly four years now. I expect this improvement to continue and to gradually gain momentum. This outlook reflects a mixture of healthy growth by households and businesses, and the dampening effects of public-sector restraint. Overall, if we were in a car, you might say we’re motoring along, but well under the speed limit. The fact that we’re cruising at a moderate speed instead of still stuck in the ditch is due in part to the Federal Reserve’s unprecedented efforts to keep interest rates low. We may not be getting there as fast as we’d like, but we’re definitely moving in the right direction.

There is indeed little doubt that the economy is on the mend. The clearest evidence can be found in housing, by far the sector hit hardest during the recession. Mortgage rates have fallen to levels rarely, if ever, seen before. Typical fixed-rate mortgages are around 3.5 percent, putting them in reach of millions of households. Affordable mortgages fuel demand for homes, and that pushes up sales and prices. Year-over-year, house prices are rising at around a double-digit rate.

The recovery in home prices has all sorts of beneficial effects. Increasing numbers of underwater homeowners are finding themselves on dry land again. Their properties are now worth more than their mortgages, making them less likely to default. Meanwhile, other homeowners find their mortgages have dropped below the critical 80-percent-of-home-value barrier. That makes it easier to refinance at today’s low rates, freeing money to spend on other things.

Homebuilders are responding to rising sales and prices. New housing construction starts have risen by more than 45 percent over the past year. As one of my business contacts put it, anything related to housing is doing well—furniture, appliances, even the pickup trucks workers drive to construction sites. That’s quite a turnaround from the past few years.

If you own a home, you’re probably feeling a little better about things, even if you don’t refinance. The rising value of your property—and perhaps your 401(k) as well—may be making you feel wealthier. Many people have responded to their improved finances by spending more on a range of goods and services. When we put it together, housing-related demand, improved access to credit, and the effects of increased wealth all have spurred consumer spending. The latest data show that, on a per-person basis, consumer spending has fully rebounded from its steep decline during the recession.

Meanwhile, businesses are hiring and increasing production. Manufacturing of durable goods such as motor vehicles and appliances has regained its previous level after plunging more than 25 percent during the recession. The recovery in durable goods also reflects the effects of lower interest rates. Of course, many businesses are still cautious. But investment in plant and equipment continues to grow moderately and is on track for further gains.

In sum, conditions in the private-sector part of the economy have improved quite a bit and continue to get better. So why then is the economy as a whole poking along instead of speeding ahead? To understand that, we need to look at what’s happening in the public sector.

When the recession hit, state and local government tax revenue tumbled. Those governments responded by cutting spending and employment, which have still not recovered. Here’s one way to see the effect those cutbacks have had on the U.S. economy: On a per-person basis, production of goods and services is about 1 percent below its pre-recession peak. But if state and local government purchases today were what they were then, output per person would be roughly where it was before the recession.

The federal government is a different story. In response to the recession, the federal government cut taxes and boosted spending substantially, and that was a big plus for the economy when it was reeling. The $800 billion tax and spending package passed in 2009 was extraordinarily expansionary, and fiscal policy overall was more stimulatory than at any time since the Great Depression.2 But that stimulus has been phasing out in recent years, leading to a substantial swing in the effects of federal fiscal policy. More recently, higher taxes have come into the picture. Income tax rates were raised on upper-income Americans, and the Social Security payroll tax cut was allowed to expire. Now, on top of that, we have sequestration. In the period ahead, as the federal deficit shrinks, fiscal policy is likely to weigh on the economy even more. The federal deficit will decline by a substantial amount, on average approximately 1½; percent of gross domestic product every year for the three years ending in 2015, according to the Congressional Budget Office.

The United States is not the only country going through a period of budgetary restraint. In Europe, government spending has grown much slower than in other recent recoveries.3 Among countries that use the euro, recessions have caused tax revenue to tank, which widens budget deficits. In the face of those enormous deficits, governments have slammed the brakes on spending. But several of these economies are still contracting. Many analysts—and some policymakers as well—have begun to wonder if policies aimed at cutting deficits should be balanced with policies aimed at spurring growth.

For the United States, Europe’s struggles are a real crimp on growth. That’s because Europe is one of our major trading partners. Europeans are buying fewer American products than they would otherwise, which damps demand at a time we need it.

However, not all the news from overseas is bad. In Japan, the central bank has adopted a much more aggressive policy to promote growth. Specifically, the Bank of Japan has officially raised the level of inflation it is targeting from 1 to 2 percent, with a view to getting the country out of a prolonged deflationary spiral. That move may not seem like much. But in central banking circles, it’s stop-the-presses news. If the Bank of Japan succeeds in jump-starting growth, that should offset some of the economic drag coming from Europe.

I’ve gone over some of the pluses and minuses influencing the U.S. economy so you can get a sense of what’s driving our moderate growth. What does this mean for the job market? Well, things have been getting better there as well. Since the low point for employment following the recession, the economy has added over 6 million jobs. During the past six months alone, we’ve added 1¼; million jobs. The unemployment rate of 7.5 percent is down 2½; percentage points from its recession peak, with nearly half a percentage point of that decline occurring in the past six months.

One reason the jobless rate has been dropping so much is that a large number of people are leaving the labor force. Many of them are reaching retirement age or going back to school. But part of this exodus appears to be people who are giving up looking for work. It’s hard to say how long these discouraged workers will stay out of the labor force. I expect many of them will return as jobs become more plentiful.

Under these circumstances, I expect the unemployment rate to decline gradually over the next few years. My forecast is that it will be just below 7½; percent at the end of this year, and a shade below 7 percent at the end of 2014. I don’t see it falling below 6½; percent until mid-2015. This forecast of a gradual downward trend in the unemployment rate reflects the combined effects of expected solid job gains and a return of discouraged workers to the labor force.

I also see a gradual pickup in overall economic growth. Growth of gross domestic product, which is the nation’s total output of goods and services, is likely to be relatively sluggish in the second and third quarters as sequestration begins to bite. But I expect the economy to gain momentum after that. I project that inflation-adjusted GDP will grow almost 2½; percent this year and 3¼; percent next year.

For its part, inflation is quite low, with the Fed’s preferred measure of prices rising only 1 percent over the past year. Wages are increasing slowly and the labor market still has considerable slack, which should restrain future wage increases. In addition, increases in the prices of imported goods and services have been subdued. And the public continues to expect low inflation. I expect that the decline in inflation will prove to be temporary, and that inflation will climb slowly, but stay below the Fed’s 2 percent longer-run target over the next few years.

Earlier I noted that the economy’s improved performance stemmed in part from Federal Reserve policies. Let me describe what we’ve done and then shift to what we might do in the future. During the recession, the Fed acted quickly and aggressively. We pushed our benchmark short-term interest rate close to zero at the end of 2008. But that move was not nearly enough to offset the damage caused by the financial crisis and the housing collapse. We couldn’t push short-term interest rates any lower. So we had to devise new, unconventional ways to stimulate the economy.

Broadly, our unconventional policies have fallen into two categories: The first involves what we say, the second, what we do. As far as what we say is concerned, our approach is centered on what is known as forward guidance. Under forward guidance, the Fed’s policy committee releases public statements about the likely stance of policy in the future. The aim is to reduce public confusion and uncertainty about future Fed policy, and thereby help us achieve our policy goals. For example, let’s take the federal funds rate, our benchmark short-term interest rate. If the Fed’s policy committee states that it expects the federal funds rate to remain exceptionally low for an extended period, that will also drive down longer-term interest rates right away. And those longer-term rates have a lot to do with whether a young family buys a house or a car, or a business builds a new factory.

The Federal Reserve’s policy committee, the Federal Open Market Committee or FOMC, has issued forward guidance that spells out specific economic conditions that serve as thresholds for considering increases in the federal funds rate. In particular, the Committee’s policy statements have specified that we expect to keep the federal funds rate exceptionally low at least as long as, one, “the unemployment rate remains above 6½; percent”; two, “inflation between one and two years ahead is projected to be no more than a half percentage point above the Committee’s 2 percent longer-run goal”; and three, longer-term inflation expectations remain in check.4

With this forward guidance in place, members of the public can adjust their expectations for future Fed policy as new information on the economy becomes available. They don’t need to wait for the Fed to issue a new statement. For example, a slowdown in economic growth might cause the public to think that the prospect of reaching a 6½; percent unemployment rate was falling further back in time. They would then expect the Fed to wait longer to raise the federal funds rate, which would prompt them to push long-term interest rates down. And those lower long-term rates would help us achieve our monetary policy goals.

The second major unconventional policy category involves what we do. Here I am speaking of our program to buy a total of $85 billion of agency mortgage-backed securities and longer-term Treasury securities each month, often referred to in the financial press as QE3. Under the current and earlier asset purchase programs, we’ve bought more than $3 trillion in longer-term Treasury and mortgage-related securities. Fed purchases boost demand for these securities, bidding up their prices and lowering their yields. Lower Treasury and mortgage yields spill over into other markets, lowering longer-term rates across the board.5

The lower rates that stem in part from forward guidance and quantitative easing have big benefits for the economy. Take a homeowner with a $250,000 mortgage. With the decline in longer-term interest rates since 2009, that homeowner might be paying around $3,000 less on a mortgage each year, if he or she is able to refinance.

Similar to our forward guidance on the federal funds rate, the FOMC has linked our asset purchases to the outlook for the economy. Specifically, we’ve said we expect to continue buying longer-term Treasury and mortgage securities until the outlook for the job market improves substantially, provided inflation remains contained. In the statement issued by the FOMC after our meeting two weeks ago, we said we would adjust our securities purchases to ensure that monetary stimulus is at a level appropriate for economic conditions. That has been a principle of our ongoing open-ended securities purchase program since we started it in September. It means we will alter the size, pace, and composition of our purchases as necessary as the economy evolves.

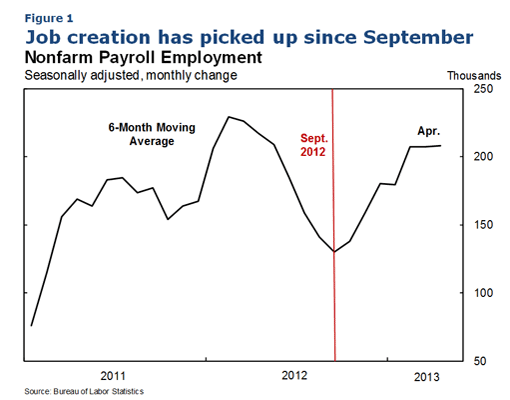

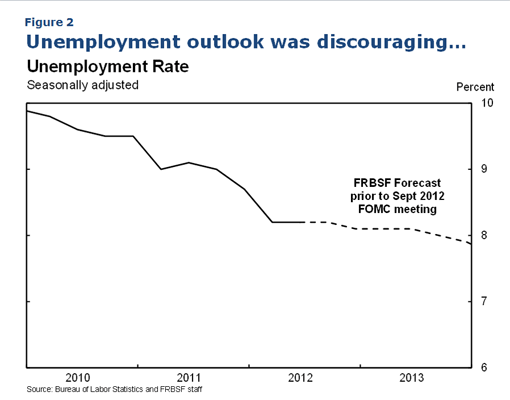

So, do economic conditions suggest we need to change the $85 billion in monthly securities purchases we’re currently making? To answer that, it’s useful to look at what conditions were when we launched the program last September. At that time, the economy was flashing warning signals. As Figure 1 shows, the pace of improvement in the labor market had slowed, with payroll growth declining. Moreover, the unemployment rate appeared to be stalled at about 8 percent, and we at the San Francisco Fed did not see the rate falling below that level till the final quarter of 2013, as shown in Figure 2.

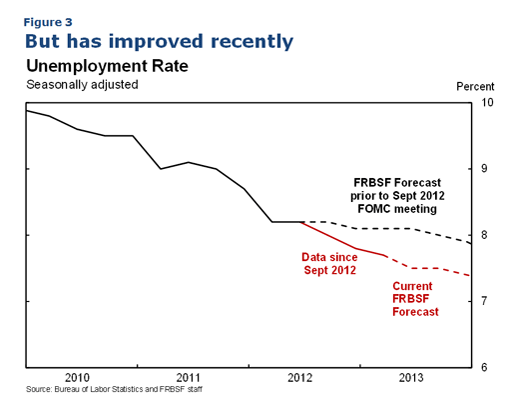

Since then, the labor market has improved considerably. The pace of job growth has picked up, averaging over 200,000 jobs per month over the past six months. And the unemployment rate has come down. Figure 3 shows that, in the seven months since our latest securities purchase program began, the unemployment rate has fallen faster than we had expected.

It’s clear that the labor market has improved since September. But have we yet seen convincing evidence of substantial improvement in the outlook for the labor market, our standard for discontinuing our securities purchases? In considering this question, I look not only at the unemployment rate, but also a wide range of economic indicators that signal the direction the labor market is likely to take.

Economists at the San Francisco Fed have identified a very good set of indicators for this purpose that tell us what labor market conditions are likely to be six months in the future. They include well-known labor market measures, such as private payroll employment growth and initial unemployment insurance claims. But they also include measures that are not as well known, such as growth in temporary help employment and survey data on the share of households that find jobs hard to get.

Consistent with the payroll and unemployment data I mentioned earlier, most of these indicators look healthier than they did in September. What’s more, nearly all of them are signaling that the labor market will continue to improve over the next six months. This is good news. But it will take further gains to convince me that the “substantial improvement” test for ending our asset purchases has been met. However, assuming my economic forecast holds true and various labor market indicators continue to register appreciable improvement in coming months, we could reduce somewhat the pace of our securities purchases, perhaps as early as this summer. Then, if all goes as hoped, we could end the purchase program sometime late this year. Of course, my forecast could be wrong, and we will adjust our purchases as appropriate depending on how the economy performs.

It’s important to stress that even if we slow the pace of our purchases, it does not mean we would be tightening monetary policy or stepping back from our commitment to provide strong monetary support as the economy recovers. The stance of monetary policy would still be extremely stimulatory. In terms of our asset purchases, the evidence shows that the stimulus we are providing depends on the size of our balance sheet, not the rate at which we’re buying assets. So even when we reduce or halt new purchases, we’ll still have trillions of dollars of longer-term securities on our balance sheet exerting downward pressure on interest rates.

Of course, eventually we will adjust our policy stance back toward normal levels. When we do, it will be because changing circumstances have made an adjustment the best way to lead us toward our mandated goals of maximum employment and price stability. We recognize that much is uncertain when it comes to the economy, and we’ve thought a great deal about how best to manage our exit from these unconventional policies. I am confident that we will succeed in doing so. Thank you.

# # #

End Notes

1. I want to thank Bharat Trehan and Sam Zuckerman for their assistance in preparing these remarks.

2. See Lucking and Wilson (2012).

3. See Kose, Loungani, and Terrones (2013).

4. See Board of Governors (2012).

5. See Williams (2011, 2012).

References

Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System. 2012. “Press Release.” December 12.

Kose, M. Ayhan, Prakash Loungani, and Marco E. Terrones. 2013. “The Great Divergence of Policies.” Box 1.1 in World Economic Outlook: Hopes, Realities, and Risks. Washington, DC: International Monetary Fund, pp. 32–35.

Lucking, Brian, and Daniel Wilson. 2012. “U.S. Fiscal Policy: Headwind or Tailwind?” FRBSF Economic Letter 2012-20 (July 2).

Williams, John C. 2011. “Unconventional Monetary Policy: Lessons from the Past Three Years.” FRBSF Economic Letter 2011-31 (October 3).

Williams, John C. 2012. “The Federal Reserve’s Unconventional Policies.” FRBSF Economic Letter 2012-34 (November 13).