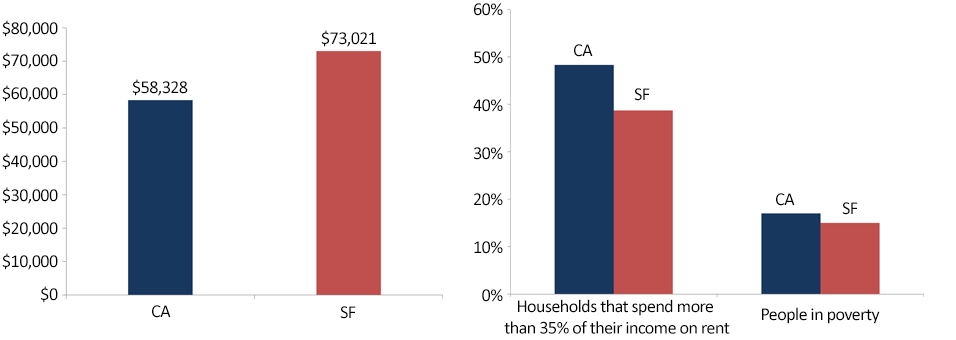

We all know that San Francisco is an expensive place to live. High cost of living has long been as characteristic of the city as the vibrant culture and foggy mornings. Yet, in recent years, housing costs have increased at a far steeper rate than in California as a whole. Today, the median cost of buying a home in the city is a million dollars, and the average asking rent is $3,057 – up nearly 10 percent from the year before. Amid these high costs, it’s worth asking how the city’s residents are getting by. When you look at some of the traditional metrics used to evaluate the health of a city, the answer is, surprisingly well. As reflected below, the median household income of the city is nearly $15,000 higher than that of California, and despite the exorbitant housing prices, the city has a smaller percentage of its population paying more than 35 percent of their income on rent than the state as a whole and a smaller percentage of people living in poverty.

Median Household Income, Rental Costs, and Poverty Rate in San Francisco

American Community Survey, 2012

While the data seems to indicate a city that is doing well on all fronts, it does not tell a complete story. Over the past five years, low-income individuals have been moving out of San Francisco at a much higher rate than they have been moving in. Whether by circumstance or choice, since 2008, the city has experienced a net loss of approximately 30,000 individuals with incomes less than $35,000.1

Migration Patterns of Individuals with Incomes less than $35,000

Moving to/from a Different County or State

American Community Survey, 2008-2012

Even with this net loss of low-income individuals, the percentage of lower-wage occupations in the area increased by 1 percent between 2008 and 2013,2 indicating that despite no longer being able to live in the city, many lower-income individuals are still working there. This raises new problems as workers are forced to commute farther for their jobs and may become disconnected from local economic opportunities. Innovative ways of thinking about affordable housing and transportation are attempting to address some of these issues, but there is no panacea, and the Community Development field is still trying to understand the breadth of the problem. We know that from a purely methodological standpoint, it is challenging to measure the true vitality of a city when the subject of our measurements is shifting so rapidly. Funding for social support services is often allocated based on quantitative metrics; therefore, it is important to ensure that those metrics are an accurate reflection of the “on the ground” conditions. These new problems require new ways of looking at data, and it seems that any measure of the health and wealth of a city should include a discussion not only of those who live there, but of those who can no longer afford to.

Notes

The views expressed here do not necessarily reflect the views of the management of the Federal Reserve Bank of San Francisco or of the Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System.