Central banks have a responsibility to share information in ways that improve the public’s understanding. This communication must be consistent enough that people can follow, and dynamic enough that it can adjust to the circumstances that are faced. Federal Reserve communications over the past 30 years have evolved to become significantly more transparent. The following is adapted from remarks presented by the president of the Federal Reserve Bank of San Francisco at the Western Economic Association International 100th Annual Conference in San Francisco on June 22.

It’s a complete pleasure to be here today and an honor to be speaking at the WEAI 100th annual conference. That’s quite a milestone, and a testament to the association’s enduring contributions to economic research. So, well done and happy anniversary.

Now, when Professor Maurice Obstfeld first invited me to speak, I thought of many topics worthy of focus. But one rose above all others, perhaps because it’s perennial, and that is central bank communication.

As researchers, and educators, you understand the importance of communicating. It is a large part of your jobs.

For central bankers, this value has often been harder to recognize. Even doubted. Communication has always come with questions: Should we communicate? How often? And what should we say?

On the question of “should we,” my answer is simple. Absolutely. Public institutions have an unequivocal obligation to share information. Central banks are no exception. It is a duty of public service to be transparent about and accountable for our actions.

But this itself is not a license to reflexively do more and more. Communication is also a responsibility, and it comes with an imperative to improve understanding. How to balance these objectives is the topic of my remarks today. I look forward to an active discussion. I want to emphasize that today I’m speaking broadly about central bank communication—my remarks are not about the Fed’s ongoing framework review.

The evolution of communication

Now, to understand where central banks might go, it is useful to know where we’ve been. And here I will narrow my focus to the Federal Reserve and the Federal Open Market Committee (FOMC).

For most of its history, the FOMC has worked under a veil of secrecy. This was intentional. Federal Reserve officials were either silent or purposely vague. As late as the June 2003 FOMC meeting, then-Chair Alan Greenspan advised participants to be “very vague” in response to questions about the conduct of monetary policy (see Federal Open Market Committee 2003). Chair Greenspan generally adhered to this approach, reputedly joking to reporters that “If I seem unduly clear to you, you must have misunderstood what I said” (Appelbaum 2012).

Instead, the Fed let financial markets learn about policies through inference, by watching movements in market interest rates. The FOMC released its first postmeeting statement in February 1994 and began to release a statement after every regularly scheduled meeting in May 1999.

The prevailing view was that less transparency promoted candid internal debate, minimized disruptive financial market reactions, and provided flexibility to respond to unexpected events (see the discussion in Federal Reserve History 2024 and Blinder et al. 2024). Moreover, many policymakers thought that they needed to surprise markets for policy to have an effect (Poole 2005).

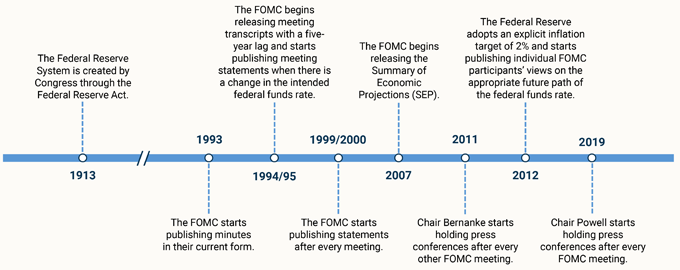

Today, the Federal Reserve is significantly more transparent, an evolution that has taken place over the past 30 years. The timeline in Figure 1 tells the story. (For a broad overview of the evolution of transparency, see Daly 2022). The FOMC now publishes meeting statements and minutes, economic projections and projected interest rate paths, a statement on longer-run goals and monetary policy strategy, and of course, an explicit inflation target (Board of Governors 2024). The Chair also holds postmeeting press conferences, and FOMC participants regularly provide their own commentary and views during intermeeting periods.

These enhanced communications have had considerable benefits. First, they have increased the public’s understanding of the Federal Reserve’s mandates and commitments. Second, as research has documented, clear monetary policy communication has helped anchor inflation expectations and helped the FOMC navigate economic shocks more effectively (Bundick and Smith 2023). Finally, these communications have allowed households, businesses, and financial markets to understand how policymakers see the economy and how they might react if things evolve differently than expected. (See, for instance, Swanson 2006. Also, recent work at the San Francisco Fed shows that the quarterly release of participant projections on the outlook for the economy and interest rates reduces investor uncertainty about the future path of interest rates. This effect is especially large around and following recessions, when uncertainty may be higher. The research will be discussed in a forthcoming FRBSF Economic Letter by Abdelrahman, Fresquet Kohan, Mertens, and Oliveira, based on past work by Mertens and Williams 2021). Ultimately, this improves the public’s ability to make good decisions.

Figure 1

Evolution of Federal Reserve Communications

Together this has improved transparency, credibility, and accountability. The reaction function of the FOMC is largely communicated through FOMC statements, the public remarks of the Chair and other FOMC participants, and the Summary of Economic Projections. All of these have helped build trust.

Given the success, many have asked if we should do more. Academics, analysts, and policymakers have offered a variety of suggestions. (See the presentations at the Federal Reserve Board of Governors’ Second Thomas Laubach Research Conference.) The ideas range from publishing details about the forecast and the risks, to doing scenario analysis, to simplifying the message and using social media to build understanding (Gorodnichenko, Pham, and Talavera 2025). Several central banks have started using scenarios in their communication with the public, including the Bank of Canada (2025), Bank of England (2025), and Sveriges Riksbank (2025). But only Sweden’s Riksbank has included a policy path in the scenarios. Former Fed Chair Ben Bernanke (2025) proposed the FOMC follow a similar tack.

The question is, how should we balance the need for transparency with the responsibility of improving understanding? To answer this question, I return to two periods of economic history.

History lessons

Let me start with the Global Financial Crisis, or GFC. As you likely remember, the recovery from the recession was painfully slow. Then-Chair Ben Bernanke and others grappled with how to implement monetary policy that was constrained by the zero lower bound on interest rates. Borrowing from academic research, they implemented a variety of alternative tools, including regular communications and strong forward guidance. This helped guide policy expectations toward a more accommodative stance, which helped support the recovery (see Campbell et al. 2017 and Bernanke 2020).

These detailed and definitive communications made sense. After all, inflation was below target, employment growth was weak, and markets weren’t sure how long the FOMC would be accommodative. In fact, markets regularly assumed interest rates would rise faster than FOMC participants expected. FOMC communications made the policy path clear and offered the support the economy needed to move back toward the dual mandate goals.

In that moment, the problem was clear, and the treatment was forceful. The success installed many of the communication tools as permanent features of the FOMC.

Then, about a decade later, the pandemic hit. Economic activity plummeted and financial markets teetered. The Fed cut interest rates close to zero and took emergency steps to support the flow of credit and liquidity. We committed to using the full range of our tools until the crisis had passed and economic recovery was well under way.

Notably, that included a commitment to keep interest rates near zero until we were confident that the economy was on track to achieve our employment and price stability goals (Powell 2020). We were very specific in our guidance, following what we had learned from the Global Financial Crisis. Our policies and communications helped stabilize markets, threw a lifeline to businesses and households, and put the economy on a quicker path to recovery (see Milstein and Wessel 2024 and Clarida, Duygan-Bump, and Scotti 2021).

This all worked, until it didn’t.

You know what happened. In 2021, inflation surged, and we needed to pivot. We raised rates aggressively and communicated strongly that we were resolute to restore price stability. These efforts have been successful and inflation is now near our 2% goal.

But looking back it could have been easier, especially on the people we serve. Our strong forward guidance in the aftermath of the pandemic firmly set public expectations, but then when the economy shifted, and inflation soared, it left people unsure about how we would respond. This concern fed into the rise in short- and medium-term inflation, which rose precipitously in this period. While there were many drivers of the global runup in inflation, and the subsequent rise in inflation expectations, our guidance likely didn’t help, at least initially (Glick, Leduc, and Pepper 2022; see Bernanke and Blanchard 2023 for a full review of the post-pandemic inflation episode).

The lesson for me from that period is that being definitive in highly uncertain times comes with a price. And we need to evaluate that price as we make future decisions about what to say. Words have power, which is a great tool. But words can be harder to reverse than the interest rate. They set expectations, which can be hard to change in the event the economy evolves differently than we expect (Walsh 2025).

Principles of communication

So, what do these two periods of history tell us? Mostly this: There is no single, simple answer. Effective communication requires a dynamic approach and continuous evaluation. What works in one situation may not work as effectively in another. Communication must be consistent enough that people can follow, and dynamic enough that it can adjust to the circumstances we face.

So, how should we choose when and what to do? For this, I look to principles.

The first is clarity. Anything we do should improve the public’s understanding of our goals, expectations, risks, or reaction function. We should always have a purpose for communicating and a way to evaluate our effectiveness. Second, any communication should enhance transparency, revealing how we think, how we make decisions, and why we reach the conclusions we do. This is the foundation of accountability. The final principle is flexibility. The economy is dynamic, and our communications must match it. Providing guidance about what we know, humility about what we don’t, and a commitment to respond to the world we get, even if it is different from the one we expect.

Like many things, these principles will sometimes be in tension, and central banks will have to balance the tradeoffs. In those moments, we need to return to why we do this at all. To be open and accountable to the public we serve.

Conclusion

I started at the Fed in 1996. I quickly learned that we were an institution that did a lot and said little. But that didn’t always serve the public. So, we changed.

But our journey shouldn’t stop here. Public institutions, like the Fed, have a responsibility to continually revisit how we communicate and how we can do better. It’s the right thing to do, and as history has taught us, it’s the best thing to do.

References

Appelbaum, Binyamin. 2012. “A Fed Focused on the Value of Clarity.” New York Times News Analysis, December 13.

Bank of Canada. 2025. Monetary Policy Report—April 2025.

Bank of England. 2025. Monetary Policy Report. Monetary Policy Committee, May.

Bernanke, Ben S. 2020. “The New Tools of Monetary Policy.” American Economic Association Presidential Address, Brookings Institution, Washington, DC. January 4.

Bernanke, Ben S. 2025. “Improving Fed Communications: A Proposal from Ben Bernanke.” Hutchins Center Working Paper 102, The Brookings Institution, May 16.

Bernanke, Ben S., and Olivier J. Blanchard. 2023. “What Caused the U.S. Pandemic-Era Inflation?” Peterson Institute for International Economics Working Paper 23-4, June 13.

Blinder, Alan, Michael Ehrmann, Jakob de Haan, and David-Jan Jansen. 2024. “Central Bank Communication with the General Public: Promise or False Hope?” Journal of Economic Literature 62(2, June), pp. 425–457.

Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System. 2024. “Statement on Longer-Run Goals and Monetary Policy Strategy.” Adopted effective January 24, 2012; as reaffirmed effective January 30, 2024.

Bundick, Brent, and A. Lee Smith. 2023. “Did the Federal Reserve Break the Phillips Curve? Theory and Evidence of Anchoring Inflation Expectations.” Review of Economics and Statistics.

Campbell, Jeffrey R., Jonas D. M. Fisher, Alejandro Justiniano, and Leonardo Melosi. 2017. “Forward Guidance and Macroeconomic Outcomes since the Financial Crisis.” NBER Macroeconomics Annual 31.

Clarida, Richard H., Burcu Duygan-Bump, and Chiara Scotti. 2021. “The COVID-19 Crisis and the Federal Reserve’s Policy Response.” Federal Reserve Board of Governors, Finance and Economics Discussion Series (FEDS) Paper 2021-35 (June).

Daly, Mary C. 2022. “This Time Is Different…Because We Are.” Speech at the Los Angeles World Affairs Council & Town Hall, Los Angeles, CA. February 23.

Federal Open Market Committee. 2003. “Transcript, June 24-25 Meeting.”

Federal Reserve History. 2024. “Transparency.” August 5.

Glick, Reuven, Sylvain Leduc, and Mollie Pepper. 2022. “Will Workers Demand Cost-of-Living Adjustments?” FRBSF Economic Letter 2022-21(August 8).

Gorodnichenko, Yuriy, Tho Pham, and Oleksandr Talavera. 2025. “Central Bank Communication on Social Media: What, To Whom, and How?” Journal of Econometrics 249(105869).

Mertens, Thomas, and John C. Williams. 2021. “What to Expect from the Lower Bound on Interest Rates: Evidence from Derivatives Prices.” American Economic Review 111(8, August), pp. 2,473–2,505.

Milstein, Eric, and David Wessel. 2024. “What Did the Fed Do in Response to the COVID-19 Crisis?” The Hutchins Center Explains, Brookings Institution, January 2.

Poole, William. 2005. “After Greenspan, Whither Fed Policy?” Remarks at the Western Economic Association International Conference (WEAI), San Francisco, CA, July 6.

Powell, Jerome H. 2020. “COVID-19 and the Economy.” Speech presented at the Hutchins Center on Fiscal and Monetary Policy, The Brookings Institution, Washington, DC (via webcast). April 9.

Sveriges Riksbank. 2025. Monetary Policy Report. March 2025.

Swanson, Eric T. 2006. “Have Increases in Federal Reserve Transparency Improved Private Sector Interest Rate Forecasts?” Journal of Money, Credit and Banking 38(3, April), pp. 791–819.

Walsh, Carl E. 2025. “Lessons for the FOMC’s Monetary Policy Strategy.” Working paper presented at the 2nd Thomas Laubach Research Conference, Washington, DC. May 15.

Opinions expressed in FRBSF Economic Letter do not necessarily reflect the views of the management of the Federal Reserve Bank of San Francisco or of the Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System. This publication is edited by Anita Todd and Karen Barnes. Permission to reprint portions of articles or whole articles must be obtained in writing. Please send editorial comments and requests for reprint permission to research.library@sf.frb.org