A decrease in oil supply drives up oil prices, which can raise unemployment and inflation. To counter adverse effects on inflation, a central bank may choose to increase its policy rate, potentially reducing economic activity further. Changing interest rates can thus shape how unexpected oil price changes affect the economy. In recent years, interest rates have become more sensitive to unexpected oil supply news. However, market-based long-term U.S. inflation expectations did not shift significantly in response to oil supply news, suggesting that the public’s inflation expectations remain well anchored.

Supply-side shocks, such as unexpected reductions in oil production or supply chain disruptions, create difficult economic conditions for policymakers to address. For example, an unexpected decline in the oil supply can raise oil prices, causing input costs to increase. Companies facing higher input costs may raise prices, which increases inflation and can lead consumers to reduce their demand for those goods, depressing economic activity and potentially raising unemployment. Central banks face a tradeoff between responding to the rise in inflation and to the rise in unemployment. In particular, the central bank may tighten monetary policy following a negative shock to the oil supply. While this would lean against rising inflation or increases in perceived future inflation, it could also further dampen economic activity.

The Federal Reserve’s ability to address such a situation depends in part on how markets expect it to respond to the oil supply shocks and how anchored market inflation expectations are to the Fed’s stated goals. Analyzing financial market responses to past oil supply shocks thus provides important insights into both the transmission of supply shocks and the ability of the Fed to effectively address them.

In this Economic Letter, we study the sensitivity of the two-year Treasury yield and long-term inflation expectations to oil supply news. We allow the sensitivity of interest rates to vary over time to examine whether the responsiveness of interest rates has changed over different economic episodes. Our analysis suggests that interest rates were more sensitive to oil supply surprises in 2022–23 relative to the pre-2021 period, though the sensitivity decreased slightly in the last few months of 2024. Furthermore, we find that inflation expectations showed little change in recent years, suggesting that market expectations of future inflation are well anchored.

Measuring oil supply surprises

To assess how sensitive interest rates are to changes in the oil supply, we need a measure of oil price fluctuations that are driven by oil production shocks unrelated to broader global economic conditions. In practice, movements in oil prices reflect both supply and demand factors. For instance, weaker global demand can lead the Organization of the Petroleum Exporting Countries (OPEC) to reduce oil production, which in turn raises oil prices.

For this analysis, we use the oil supply “surprises” series from Kanzig (2021). These surprises are defined as changes in daily oil futures prices around OPEC press conference announcements. Because oil futures are forward-looking, their prices incorporate publicly available information. Global economic conditions are likely already known and have been priced in by the market before an announcement, so the short-term change in prices following the announcement should isolate the effect of the news itself on oil prices. The series includes 151 surprises, spanning from July 1983 to December 2024, and captures both positive and negative shocks to oil prices.

Measuring interest rate sensitivity

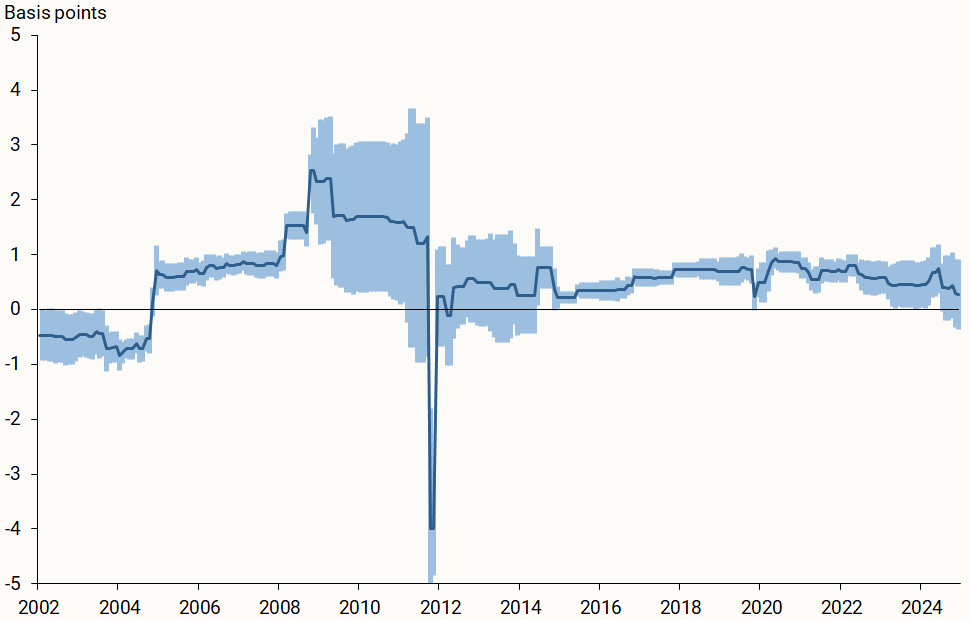

We estimate the sensitivity of two-year Treasury yields to oil supply news by examining the daily changes in yields on OPEC announcement days using 36-month rolling samples starting in 1983. Each point on the blue line in Figure 1 shows the estimated sensitivity for the 36-month sample ending in the month indicated on the horizontal axis. For example, the point estimate for January 1986 is the sensitivity of interest rates to oil supply news between February 1983 and January 1986. The light blue shading indicates the 90% confidence bands for these estimates, which show the statistical uncertainty around each estimate. In particular, assuming our model is correct, the confidence bands contain the true market response roughly 90% of the time.

Figure 1

Two-year Treasury yield sensitivity to oil supply surprises

The response of the two-year yield to oil supply news changes over time in both magnitude and direction. At the beginning of our data for rolling samples up to 1990, the two-year Treasury yield showed little sensitivity to oil supply surprises. In contrast, interest rates in the late 1990s tended to rise following negative oil supply news, suggesting that financial market participants may have expected the Fed to respond more strongly. In the early 2000s, news about oil supply declines is associated with a drop in the two-year yield: A typical one standard deviation oil news shock increased oil prices by 3% and decreased the daily two-year yield by 3 basis points (hundredths of a percentage point). We observe a similar pattern for six-month federal funds futures in response to oil supply news, indicating that financial markets expected the Fed to respond less aggressively over a six-month horizon to inflationary pressures stemming from an oil supply disruption than it had in the 1990s.

The sensitivity of two-year Treasury yields increased substantially between March 2022 and August 2024. An oil supply surprise that typically increases oil prices by 3% resulted in two-year yields rising as much as 4.5 basis points in early 2024. This reaction is more than three times larger than during the pre-2021 period. Interest rate sensitivity began to rise in March 2022, coinciding with “liftoff,” when the Federal Reserve began to raise the policy rate from zero. Our findings are consistent with Bauer, Pflueger, and Sunderam (2025), who observed heightened sensitivity of financial markets and forecasters to consumer price index and nonfarm payroll news after liftoff. In the last four months of 2024, the sensitivity of the two-year Treasury yields had fallen back to 2023 levels. This result may be interpreted as financial markets beginning to anticipate the Fed taking a tougher stance against inflation after it began raising the policy rate. We note that the low sensitivity of interest rates to oil supply news before liftoff may be a result of the zero lower bound on the federal funds rate and market expectations that the rate would be near zero for some time, making the two-year interest rate unable to adjust at the margin.

We also examine the sensitivity of the short-term interest rate using the three-month Treasury yield and the long-term interest rate using the ten-year Treasury yield, as well as different forward rates. Our results show that these interest rates are roughly consistent with the two-year yield pattern, where interest rates were expected to fall in response to oil shocks in the early 2000s but expected to rise in recent years.

Although the sharp rise in sensitivity in 2023–24 may be interpreted as the market’s belief that the Fed had recently prioritized the fight against inflation, there are alternative explanations. First, structural changes in the U.S. economy could influence interest rates’ responses to oil supply news, independent of any change in the Fed’s stance. Notably, the United States transitioned from a net oil importer to an oil exporter in 2011. This shift may have fundamentally changed how oil shocks affect economic activity and inflation. Second, the perceived persistence of oil supply changes has varied over time, altering the effects of these shocks and potential policy responses. Leduc, Moran, and Vigfusson (2023) document that changes in oil prices were seen as largely temporary in the early 2000s but were seen as more persistent in the 2002–08 period. Since 2014, however, the perception of how long oil supply shocks would last has fallen.

The reaction of inflation expectations to oil supply

Supply shocks can increase inflation expectations for both consumers and businesses, which can make it harder for the Fed to control actual inflation. To examine how inflation expectations have responded to oil supply surprises over time, we estimate the response of long-term inflation expectations to oil supply surprises using rolling 36-month samples. We employ the daily market-based inflation expectations series developed by Gurkaynak, Sack, and Wright (2007).

Figure 2 displays the sensitivity of the 10-year breakeven inflation compensation to oil supply surprises over 36-month samples that end in the month indicated on the horizontal axis. We use inflation expectations data from 1999 to 2024, such that the starting point on the graph is the estimated sensitivity for the February 1999 to January 2002 period.

Figure 2

Ten-year inflation expectations sensitivity to oil surprises

The responses of the market-based inflation expectations to oil supply news varies somewhat over time. In the most recent period, however, long-term inflation expectations have declined following oil supply surprises. This result suggests that, as the Fed responded to oil shocks with more aggressive interest rate hikes, inflation expectations became better anchored. Overall, the small and stable responses of long-term inflation expectations in samples after 2014 are also indicative of the Fed’s credibility among financial market participants.

We note that the large drop in sensitivity at the end of 2011 was driven by the late 2008–09 observations, when the liquidity premium in the bond markets surged, leading to a massive drop in breakeven inflation compensation.

Conclusion

Negative oil supply shocks and supply chain bottlenecks are important sources of business cycle fluctuations. These shocks create a dilemma for policymakers, who may face a tradeoff between fighting inflation and a decline in economic activity. In this Letter, we document that interest rates exhibit a time-varying response to oil supply announcements. Notably, interest rates have become more sensitive to oil supply announcements since the Federal Reserve’s 2022 policy rate liftoff, while long-term inflation expectations have remained well anchored. These findings suggest that financial market perceptions of how the Fed responds to oil shocks evolved following the Fed’s policy actions in 2022. Our results also highlight the Fed’s credibility, as the market-based long-term inflation expectations remained well anchored in response to oil supply announcements.

References

Bauer, Michael, Carolin E. Pflueger, and Adi Sunderam. 2025. “Current Perceptions About Monetary Policy.” FRBSF Economic Letter 2025-05 (February 24).

Gürkaynak, Refet S., Brian Sack, and Jonathan H. Wright. 2007. “The U.S. Treasury Yield Curve: 1961 to the Present.” Journal of Monetary Economics 54(8), pp. 2,291–2,304.

Känzig, Diego. 2021. “The Macroeconomic Effects of Oil Supply News: Evidence from OPEC Announcements.” American Economic Review 111(4), pp. 1,092–1,125.

Leduc, Sylvain, Kevin Moran, and Robert J. Vigfusson. 2023. “Learning in the Oil Futures Markets: Evidence and Macroeconomic Implications.” The Review of Economics and Statistics 105(2), pp. 392–407.

Opinions expressed in FRBSF Economic Letter do not necessarily reflect the views of the management of the Federal Reserve Bank of San Francisco or of the Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System. This publication is edited by Anita Todd and Karen Barnes. Permission to reprint portions of articles or whole articles must be obtained in writing. Please send editorial comments and requests for reprint permission to research.library@sf.frb.org