The change in the average U.S. tariff rate in 2025 was the largest in the modern era. One way to assess the effects of such a large shock on unemployment and inflation is by looking at data from pre-World War II periods with tariff rate changes of a similar magnitude. Analysis shows that previous tariff hikes raised unemployment and reduced both economic activity and inflation. Uncertainty may be a factor behind these effects: A large tariff increase raises uncertainty, which can depress overall demand and lead to lower inflation.

The 15% increase in the average U.S. tariff rate in 2025 was the largest in the modern era. Assessing the likely impacts of such a large and sudden change, or tariff shock, on unemployment and inflation is crucial for monetary policy discussions. In general, if a tariff shock raises inflation, tighter monetary policy could help tame the inflation increase, if other factors remain constant. By contrast, if a tariff shock has little effect on inflation but leads to an increase in unemployment, loosening monetary policy could be helpful.

However, there is little consensus on the overall economic effects of tariff shocks—mainly because there have not been such large changes in tariff rates for decades. Since World War II, global tariffs have steadily fallen under the General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade (GATT), dropping from 10% in 1945 to under 3% by January 2025. The last time average tariffs were above 15% was during the interwar period between World Wars I and II.

In this Economic Letter, we take a historical perspective and study the effects of tariff rate changes in past eras, specifically when changes were similar in speed and magnitude to those in 2025. In particular, we look back at the so-called first wave of globalization—the period of increased global economic integration in trade and finance between 1870 and 1913—as well as the interwar period. These two eras saw large fluctuations in tariff rates.

Analysis shows that shifting policy priorities—rather than reactions to contemporaneous economic conditions—were the main drivers of tariff adjustments from past eras. We find that these tariff hikes raised unemployment, which slowed economic activity, while simultaneously lowering inflation.

Background from historical data

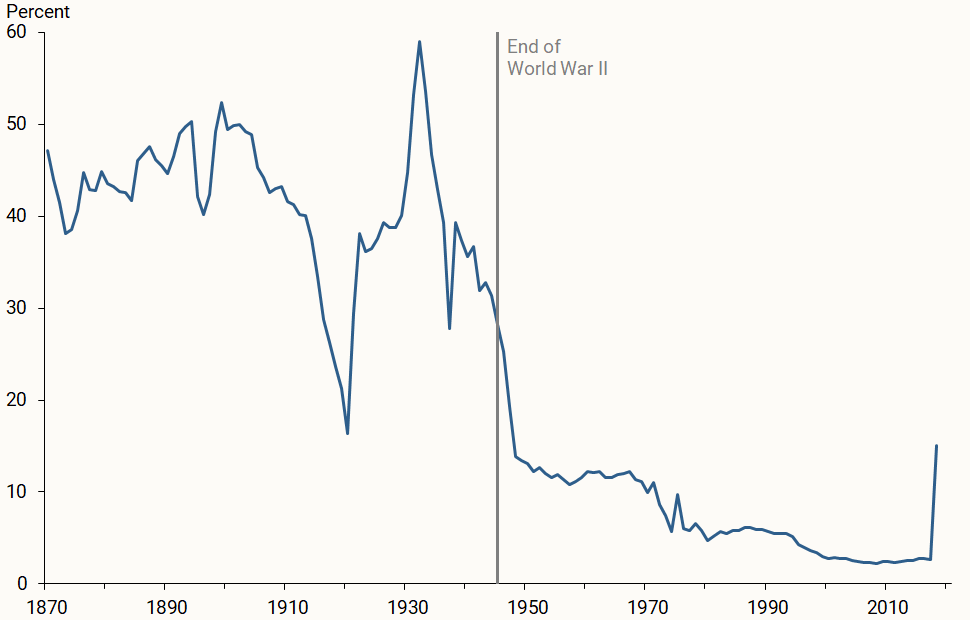

While numerous theoretical studies have analyzed the economic effects of changes in tariffs (see, for example, Rodríguez-Clare, Ulate, and Vasquez 2025), there has been little empirical work on the topic, and recent studies have been limited to post-1960 variation (see, for example, Schmitt-Grohé and Uribe 2025). Since World War II, global tariffs have steadily fallen under GATT agreements, dropping from 10% in 1945 to under 3% by January 2025. Figure 1 illustrates the average tariff rate in the United States since 1865, showing that the last time average tariffs were above 15% was before World War II. Major tariff changes have been absent in recent history until 2025.

Figure 1

Average U.S. tariff rate for all imports

However, during the first wave of globalization—the period of increased global economic integration in trade and finance between 1870 and 1913—and the interwar period, tariff rates displayed large fluctuations that were similar in size and speed to the 2025 average tariff rate increase. Indeed, while the general trend has been downward over the past 150 years, earlier periods show that tariffs occasionally rose or fell as much as 20 percentage points in a year.

Estimating the effects of unexpected tariff changes on the economy

The large and abrupt tariff changes in the historical data can provide some insights into how tariffs affect inflation and economic activity. However, it could be misleading to assume that the data depict a relationship between the two. If tariff rates could change in response to economic conditions, subsequent economic activity may simply reflect the normal evolution of the economy rather than the effects of tariffs. For example, if policymakers thought that higher tariffs helped raise employment in the short run by making imports more expensive and thereby boosting spending on domestic goods, they might raise tariffs whenever the unemployment rate started increasing to protect domestic workers. In that case, the data might appear to mistakenly suggest a correlation between higher tariffs and higher unemployment.

To learn about the causal effects of tariff changes, one must isolate the changes in tariffs that are independent of the state of the economy, such as those associated with policy shifts following elections. For example, in the 1888 presidential election, Benjamin Harrison defeated incumbent Grover Cleveland by a narrow margin, when the economy was neither in a recession nor overheating. The Harrison victory led to the Tariff Act of 1890—also known as the McKinley tariff—which raised average tariffs to almost 50%. That change was driven by the new administration’s policy stance that tariffs were needed to protect domestic industries from cheaper foreign competition. Since the tariff change was motivated by long-run considerations, we can study its effect by observing how inflation and economic activity fared in the years afterward. We acknowledge that other developments could have also influenced the economy. However, by averaging over many such tariff changes, we can isolate the effects of tariffs on the economy in that period.

In Barnichon and Singh (2025), we carefully reviewed the major historical tariff changes in the United States since 1870. We found no systematic relationship between the state of the economic cycle and the direction of tariff changes. This reflects that, throughout the 19th century and up until 1935, elected officials from different parties held opposite views on the desirability of tariffs. One side favored higher tariffs to protect their constituents in industrialized regions. The other favored lower tariffs because their constituents were focused less on industry and more on imported goods. Since changes in the economic cycle are not associated with either side winning elections, there was no general relationship between the direction of tariff changes and the state of the economy. Thus, relying on this “narrative identification” approach, we can study the causal effects of tariff shocks using simple regressions of economic activity or inflation on tariff changes.

Estimating tariff effects

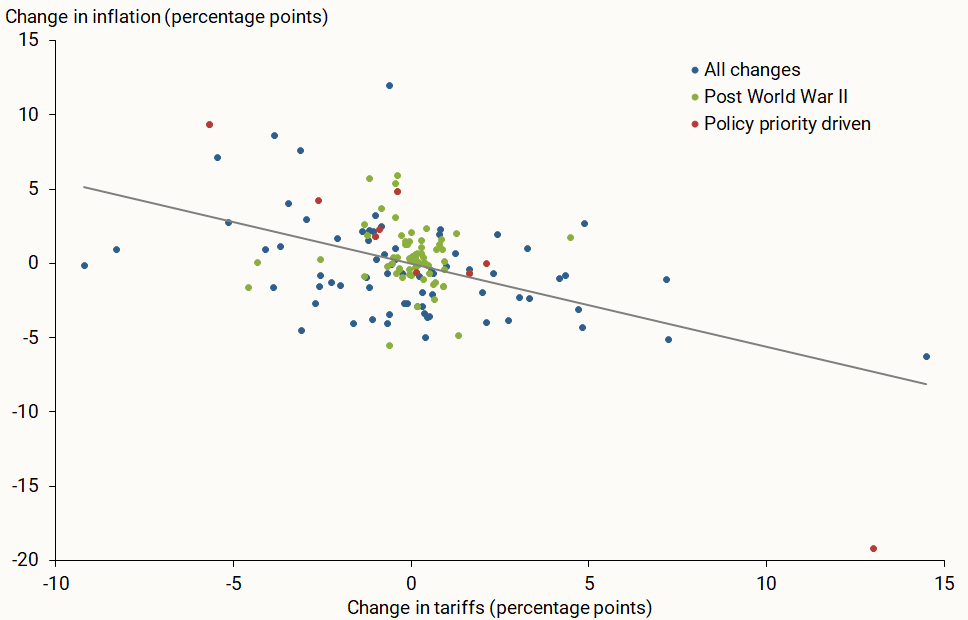

The dots in Figure 2 show each case of a change in the average tariff rate, either positive or negative, on the horizontal axis and the changes in inflation in the year of that tariff change on the vertical axis. The data suggest a strong negative correlation between changes in tariffs and inflation: A 1 percentage point increase in tariffs is associated with a 0.6 percentage point decline in inflation. Focusing only on large tariff changes that can be directly tied to shifting policy priorities gives very similar results, as indicated by the red dots in the figure.

Figure 2

Tariff changes and inflation changes, 1886-2017

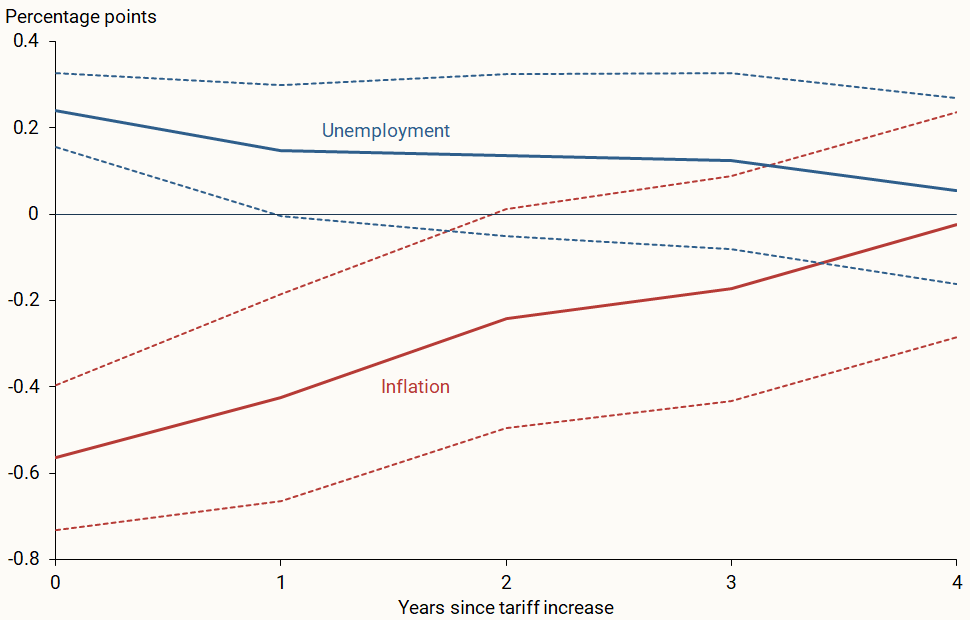

Next, to estimate the dynamic effects of tariff changes, we use a statistical model called a vector autoregression, which allows us to capture the effects of shocks over time after making mild assumptions about the underlying economic structure (see Barnichon and Singh 2025 for details). Figure 3 shows the responses of inflation and unemployment over time following a 1 percentage point increase in the tariff rate.

Figure 3

Tariff increase effect on inflation, unemployment: 1869-1941

Source: Historical Statistics of the United States (1976) and authors’ calculations.

The figure suggests that a temporary tariff increase leads to a rise in unemployment (blue line) and a decline in inflation (red line) that both last up to two years after the initial shock before becoming statistically insignificant. In other words, and perhaps surprisingly, our estimates show that an increase in tariffs decreases inflation.

How can higher tariffs lower inflation?

One prominent theory about tariff shocks is that they tend to drive up domestic production costs through more expensive imported inputs while raising the prices of final goods that are made abroad (see, for example, Werning, Lorenzoni, and Guerrieri 2025). Under this framework, higher tariffs would be expected to lead to lower economic activity and higher inflation in the short run.

Our estimates suggest the opposite, however, with shocks from higher tariffs leading to both higher unemployment and lower inflation. A possible explanation relies on the effects of uncertainty: A tariff shock tends to coincide with an uncertain economic environment, which by itself depresses economic activity by lowering consumers’ and investors’ confidence and puts downward pressure on inflation (see, for example, Leduc and Liu 2016). Another possible explanation is that an adverse tariff shock leads to a drop in asset prices, which then depresses overall demand and leads to higher unemployment and lower inflation.

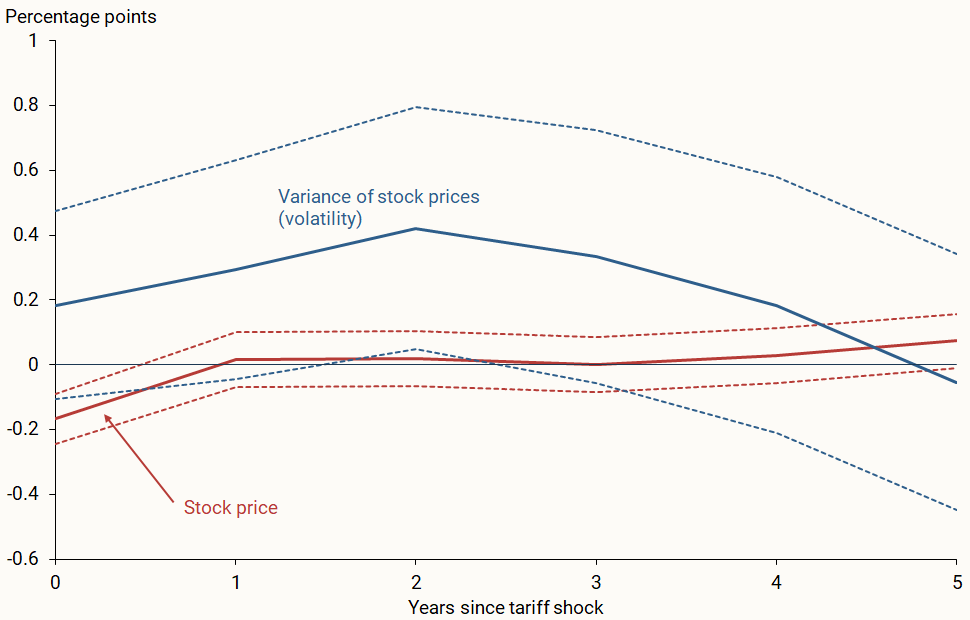

To study the plausibility of these two mechanisms, we use our statistical model to estimate the effects of tariff shocks on a common stock price index and on stock market volatility as a proxy for uncertainty. Figure 4 shows that both uncertainty (blue line) and a drop in stock prices (red line) are plausible explanations for the economic effect of tariffs. The immediate effect of higher tariffs on stock prices is negative, but the effect quickly fades within the first year. Stock market volatility increases notably after the tariff shock, although the estimates are statistically precise only in the first and second year after a tariff increase.

Figure 4

Tariff increase effect on stock prices, volatility: 1869-1941

Source: Historical Statistics of the United States (1976) and authors’ calculations.

Conclusion

In this Letter, we show that large and abrupt tariff increases before World War II were associated with lower inflation and higher unemployment, potentially spurred by higher uncertainty and lower wealth. Because many aspects of the economy were different a hundred or more years ago, those historical experiences may not fully apply to current conditions. For instance, the share of imported inputs in production is higher today than in the past, which means a tariff shock may be more likely to raise inflation (Bergin and Corsetti 2023). Nevertheless, our analysis of historical data highlights a possibility that the large tariff increase of 2025 could put upward pressure on unemployment while putting downward pressure on inflation.

References

Barnichon, Regis, and Aayush Singh. 2025. “What Is a Tariff Shock? Insights from 150 Years of Tariff Policy.” FRB San Francisco Working Paper 2025-26.

Bergin, Paul, and Giancarlo Corsetti. 2023. “The Macroeconomic Stabilization of Tariff Shocks: What Is the Optimal Monetary Response?” Journal of International Economics 143(103758).

Leduc, Sylvain, and Zheng Liu. 2016. “Uncertainty Shocks Are Aggregate Demand Shocks.” Journal of Monetary Economics 82, pp. 20–35.

Rodríguez-Clare, Andrés, Mauricio Ulate, and Jose P. Vasquez. 2025. “The 2025 Trade War: Dynamic Impacts Across U.S. States and the Global Economy.” FRB San Francisco Working Paper 2025-09.

Schmidt-Grohé, Stephanie, and Martin Uribe. 2025. “Transitory and Permanent Import Tariff Shocks in the United States: An Empirical Investigation.” NBER Working Paper 33997.

Werning, Iván, Guido Lorenzoni, and Veronica Guerrieri. 2025. “Tariffs as Cost-Push Shocks: Implications for Optimal Monetary Policy.” NBER Working Paper 33772.

Opinions expressed in FRBSF Economic Letter do not necessarily reflect the views of the management of the Federal Reserve Bank of San Francisco or of the Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System. This publication is edited by Anita Todd and Karen Barnes. Permission to reprint portions of articles or whole articles must be obtained in writing. Please send editorial comments and requests for reprint permission to research.library@sf.frb.org