As this volume has shown, relatively few well-organized programs are aimed at

strengthening middle neighborhoods. Two exceptions are the Healthy Neighborhoods

programs in Baltimore and Milwaukee,1

both are asset-based and

market-driven programs. They are asset-based because their basic premise is that

the neighborhoods they target have many assets and reasons to live there, which residents,

real estate agents, and potential newcomers often overlook. The programs generally choose

neighborhoods that have few vacant properties and a strong community organization, yet a

housing market that is persistently stagnant. The program is market-driven because it understands

that its target neighborhoods exist in a market (neighborhoods compete with one

another for residents and investment), and the goal of the program is to strengthen their

competitive position in the city or regional market.

In many respects, Healthy Neighborhoods is a twenty-first century version of the Neighborhood

Housing Services (NHS) organization begun in Pittsburgh in 1968, and promulgated

by NeighborWorks America. Like NHS, Healthy Neighborhoods targets middle neighborhoods

and combines efforts of neighborhood residents, lenders, city government, and the

nonprofit sector to prevent abandonment, increase investment, particularly in homeownership,

and stabilize or increase property values. All this is done in an effort to protect and

expand homeownership equity. However, unlike the NeighborWorks model, there are not

income restrictions on who can participate in the program.

The Key Elements of the Healthy Neighborhoods Model

The programs in Baltimore and Milwaukee seek to increase homeownership in their target

neighborhoods by marketing (with incentives) the neighborhoods to existing residents and

prospective buyers. The goal is to improve these neighborhoods and to make it more likely

that homeowners will be able to build equity through increased home values.

Operationally, the programs follow similar principles. These are:

- Improve the neighborhood by working from the strongest areas outward. This

approach targets neighborhood improvement by building on assets rather than fixing

the biggest problems. This principle may appear to be counterintuitive, but building

from the strongest areas spreads market strength and avoids the common problem of having investments made in weak areas chewed up by decline, and uses scarce

financial resources wisely. This strategy gains momentum from success that can be

reinvested, improvement-by-improvement, until it affects the entire neighborhood.

For example, if a quality school is an asset for a particular neighborhood, then efforts

should focus on building additional support in the community for that school. This

could mean working with the school principal and staff to offer additional recognition

and access to school facilities or afterschool activities. Helping current and prospective

parents connect with the school as a resource is one approach to neighborhood

improvement. It can also mean connecting with real estate agents so they know that

the schools will be an important asset in marketing homes in the neighborhood. - Support residents in working together to establish and enhance individual neighborhood

identities by marketing strengths. This is often accomplished by direct

neighbor-to-neighbor contact, in which residents focus on what they like about their

neighborhood, and not on its liabilities. As a starting point, everyone should know the

name of their neighborhood and be able to articulate the key reasons for living there.

There should be general agreement about what is important and why most people

choose to live there. Knowing neighborhood history helps to build this solidarity, as

do programs such as walking tours, community newsletters published by residents,

and other similar efforts. This positive approach can be challenging because neighborhood

residents are typically organized to confront problems and their sources.

Helping resident associations adopt positive messaging while still confronting the

sources of neighborhood problems requires ongoing coaching and technical help.

Residents must find the right balance between promoting the neighborhood as a

good place to live, while demanding solutions to problems from city government

when warranted. - Help residents become spokespeople and “sales agents” for the area. Healthy Neighborhoods

programs help organize active residents to speak articulately about their

neighborhoods and actively promote its virtues to friends, relatives, and coworkers.

Baltimore uses the terms “neighborhood ambassadors” or “‘I Love City Life’ ambassadors”

for its program of city residents who are actively involved in the community

and volunteer at neighborhood events and other opportunities. The positive messages

about the neighborhoods are also conveyed through active, well-maintained websites,

given that large numbers of homebuyers use the web to scout out homes and neighborhoods.

Of course, neighborhood “sales agents” must work with the real estate

agents who sell homes in the neighborhoods to ensure they have up-to-date information

on the assets in the neighborhoods and the positive activities underway. - Help people of all income levels invest in their properties by offering economic

incentives to get financing for home improvements. To encourage people to invest

in their properties, Baltimore’s Healthy Neighborhoods program has organized with

a group of lenders in a loan program to provide home improvement loans and home

mortgages at slightly below-market prices, which residents can access in an expedited

manner. All the loans require some home renovation, particularly on home exteriors. Healthy Neighborhoods encourages homeowners to make external, visible improvements

because these changes can become contagious in a positive way, with homeowners

following suit once they see their neighbors making improvements. Loans can

exceed the after-rehabbed value of the home. - Market the neighborhood and its assets to people who may want to move in—and

knowing the market segments that are likely to move into the neighborhood.

A key starting point is simply to market the neighborhoods to people with similar

income levels and to be strategic in reaching out to those who would find the neighborhoods

attractive as a place to live and invest. The Internet is the most important

means of communication. - Tackle crime aggressively. People do not choose to live in unsafe neighborhoods.

- Clean up physical problems in the neighborhood. Vacant homes, uncut lawns,

abandoned cars, and vacant and littered lots must be tackled to improve the look of

the neighborhood. Philadelphia offers as a model the vacant land treatment program

created by New Kensington CDC, along with the Pennsylvania Horticultural Society,

which is a bottoms-up approach to controlling abandoned land. - Help residents be directly involved and take personal responsibility to improve

their blocks through small, inexpensive improvement projects. Not only do

greening, improved lighting, and other efforts help to beautify a neighborhood and

improve home values, but the process of making the improvements also helps to

create a community fabric. Contrary to conventional beliefs about neighborhood

revitalization, an effective strategy is to go to the strongest block in an area and support

a park or school, rather than just focusing on a group of kids causing trouble on a

corner. Rather than merely focusing on solving the toughest, most expensive physical

problems, the efforts should build on the existing strengths of these areas—leveraging

them to make them even stronger and more self-sustaining. In addition to supporting

residents’ investments in their own properties and acting as agents for their neighborhood,

the Healthy Neighborhoods goal is to help residents to take action that helps

them to have a sense of ownership of and connection to where they live. - Build community spirit through picnics, block parties, and other festive events.

These activities make it fun to live in the neighborhood and build stronger bridges

among different groups (young and old, schools and community, etc.). Living in a

good neighborhood is about people enjoying living together, not about spending

time complaining about problems. Events that celebrate the quality of life that people

have chosen helps to build community spirit. Neighborhood greening and “farming”

activities are also important marketing activities. - Tailor approaches to suit particular neighborhood conditions and see to it that

the different assets of the neighborhood fit together and reinforce one another. This may lead to different strategies for different places—a focus on “aging in place”

for neighborhoods with large numbers of seniors, a school-focused strategy to increase

resident involvement in school improvement efforts, and similar targeted approaches. - Measure results as a means to provide feedback to resident leaders and their

partners on progress or lack of it. Although stories about actions that improve

neighborhoods are of value, hard data matter more. The Healthy Neighborhoods

programs track changes in property values through sales price changes, days on

market, the number of rehabilitation permits issued, changes in the number of

vacant properties -–all data that is locally available and relatively easy to collect and

report on.

Several critical elements underlie each of these principles:

- Residents, merchants, property owners, and neighborhood institutions must take

responsibility for improving their neighborhood. - Concessionary rate and non-income-restricted mortgages are a critical incentive for

improvement and investment given that neighborhoods compete for homebuyers. - Government is supportive of, but does not lead, the process. Government identification

with neighborhood improvement efforts can have the unintended consequence

of damaging neighborhood confidence by sending the message that the neighborhood

is bad enough to need government support. Government’s role is to make the

streets safe, invest in infrastructure as needed, pick up trash and keep the neighborhood

clean, and improve schools. In addition to providing these city services, Baltimore

city government provides local funds without income restrictions on the users

to stimulate homeownership and investment in the neighborhoods. Using incomerestricted

funds complicates the simple message that these are neighborhoods where

anyone can and will buy a home. It instead suggests that the only buyers are low- and

moderate-income households who are moving in because they are receiving federal

support. - Execution of the plan in each neighborhood will, and should, vary. The approaches

are by no means “neighborhood improvement by formula,” but rather, approaches

that seek to unleash invention and creativity in neighborhoods. Successful execution

requires significant volunteer time and energy and neighborhood leadership. - Many forces will work against the improvement of these areas. Although these neighborhoods

may seem “good enough” to some, hard work is needed to ensure they are

on a path to becoming improved places to live and invest. - The neighborhoods must be carefully selected. They must be large enough that

their improvement can spread to bordering areas, yet the strategies targeted enough

that change is visible in a year or two. Residents and outsiders alike must develop a

growing confidence that the neighborhood is on the road to improvement. - A nonprofit organization should serve as an intermediary between neighborhood

leadership, city government, the school board, lenders, and other partners. In Baltimore,

this nonprofit is Healthy Neighborhoods, Inc., which was incubated by the

Baltimore Community Foundation and then spun off. In Milwaukee, the nonprofit

is the Greater Milwaukee Foundation.

The Experience in Baltimore

The Healthy Neighborhoods program was begun in 2004 as a pilot program of the Baltimore

Community Foundation (BCF) with the single goal of strengthening middle neighborhoods

in a city that had been losing population since the end of World War II. BCF

raised the initial funds for the program and recruited a strong board, which consisted of

executive leadership from three banks, foundations, and other civic leaders. The board hired

a seasoned president with substantial knowledge of Baltimore neighborhoods and housing

finance, and a deputy who had been leading a middle neighborhood program in Baltimore.

During the program’s 10-year history, it has worked with 14 neighborhood groups to

improve 41 neighborhoods, with private and public capital exceeding $150 million in investments

in these neighborhoods. Healthy Neighborhoods chose neighborhoods through a

“request for proposal” competitive process. Neighborhoods must have met the definition of

a middle neighborhood, and neighborhood groups were selected on the basis of neighborhood

capacity and willingness to participate in an approach that builds on assets and property.

Each neighborhood receives $40,000 annually for program staffing, and each neighborhood

is also eligible to receive funds to take on community improvement projects.

The neighborhoods targeted their efforts to the strongest blocks in the neighborhood,

following the “build from strength” principle. The program leaders also understood that

private financing could provide attractive terms and incentives without income or price

restraints. Healthy Neighborhoods organized a pool of loans from 10 lenders totaling $40

million. These loans were special in two ways. First, the loans could be up to 120 percent of

post-rehab appraised value. Three local foundations and the Maryland Housing Fund made

these loans possible by guaranteeing the top 10 percent of losses to the lenders. Second,

loans were made to qualified buyers at a percentage point below market rates as in incentive

to draw buyers into the neighborhoods. No mortgage insurance premium was charged to the

borrowers. A second $30.5 million loan pool was organized when all the funds from the first

were committed. In all, these loan pools have originated 352 loans totaling $53.6 million.

Defaults have cost the program 2.5% of capital. In addition to mortgage loans, the program

provides matching grants of up to $10,000 to homeowners who are willing to improve their

homes. This program component has led to 179 rehabbed homes, with $1.6 million allocated

in matching grants.

Baltimore City has been supportive of the HNI program, providing city funds for operations

and matching grants. These funds are local funds, not federal funds, because federal

funds, such as Community Development Blog Grants or HOME funds, carry restrictions on

the borrowers’ incomes. The programs provide ongoing training and mentoring for nonprofit

staff and board on the specifics of the Healthy Neighborhoods model. This training includes

content on marketing and organizing, loan products, advice on development projects, public

policy, and block projects to help neighbors feel more positive about their neighborhoods.

Forty-one neighborhoods have participated in the program, supported by 12 neighborhood (sometimes CDC) organizations. The program is modest to operate compared with most

community development programs. The annual program costs in 2015 were $1.3 million.

The Baltimore program was also a successful applicant for Neighborhood Stabilization

Funds from the federal government and used these funds to work with developers to successfully

renovate and sell 205 formerly vacant or foreclosed housing units in the targeted neighborhoods.

Although the NSP component is not a fundamental part of the Healthy Neighborhoods

model, its use in Baltimore’s targeted neighborhoods has had a significant impact

on home values and neighborhood conditions.

The program monitors its own progress quarterly, measuring its success through changes

in sales prices of homes, rehab permits issued, and days on market of homes (to measure

market strength) as well as other real estate measures. Through 2008, results were positive,

with neighborhood values keeping up with or exceeding the city’s trend lines. The recession

did harm the city and those neighborhoods particularly where development drove up values

artificially or there was predatory lending. However, home values are again increasing in

these neighborhoods.

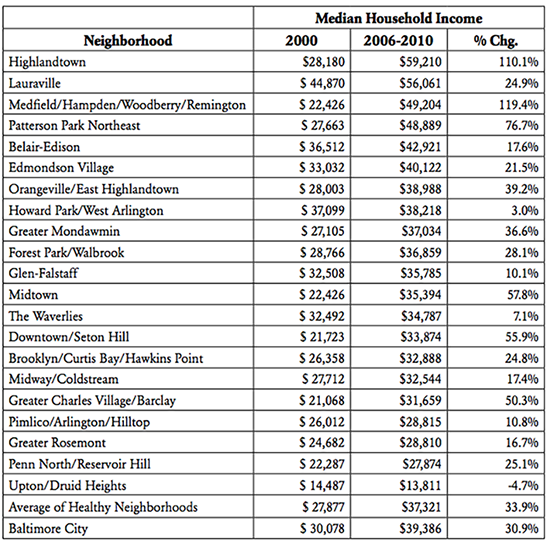

The program is successfully improving these neighborhoods and their competitiveness,

without gentrification. The median income in the middle neighborhoods in Baltimore has

risen, on average, slightly above that of the city overall. The three neighborhoods that experienced

a sharp rise in median income are near Johns Hopkins University and adjacent to

neighborhoods with very strong markets. Even in these neighborhoods, what is occurring is

not gentrification, but a slow replacement of owners who have aged in place with newcomers

who have higher incomes. However, the essential character of the neighborhoods has not

been disrupted.

Table 1

Median Income in Select Baltimore Neighborhoods

Revitalizing Milwaukee’s Middle Neighborhoods

Milwaukee has been working to improve middle neighborhoods for over a decade. In

2006, the Greater Milwaukee Foundation launched the Healthy Neighborhoods Initiative, a

public-private partnership with the city of Milwaukee. The program has operated in 18 neighborhoods

in Milwaukee and two neighborhoods in Waukesha, a nearby suburb. The program

targets neighborhoods in the middle, those generally stable, affordable places that are neither

high-demand neighborhoods promoted by real estate agents nor the distressed neighborhoods

receiving public policy attention. They are, nonetheless, neighborhoods important to

the future well-being of the city.

Healthy Neighborhoods’ Approach

Milwaukee Healthy Neighborhoods program has three main goals:

- Restore market confidence in selected neighborhoods through investment, reinvestment,

and strategic physical improvements; - Help neighborhood residents build wealth, primarily by restoring homeowner equity

and market appreciation; - Strengthen and enhance the social fabric of neighborhoods by supporting neighborhood

organizations and community-building activities.

The foundation identifies and works with designated neighborhood lead organizations

that engage residents and manage the program on the ground. They helped residents improve

more than 1,300 properties, representing more than $23 million in neighborhood reinvestment.

The foundation also collaborates with a broad array of public and nonprofit organizations

that agree to work together to make the program successful. Neighborhood lead

organizations must be committed to Healthy Neighborhoods values, have dedicated staff,

systems for finance and administration, and sources of funding other than the foundation.

Resident engagement is a key driver of success for the program. Since its inception, more

than 900 block activities and community events have engaged more than 70,000 residents.

More residents are choosing to invest in their homes because the program is increasing their

confidence that their neighborhood is improving. This was evident in 2015 when 59 homeowners

in the Silver City, Burnham Park, and Layton Park neighborhoods participated in the

Most Improved Home Contest. The residents invested more than $232,800 in curb appeal

enhancements that boost neighborhood appearance, pride, and confidence.

The Foundation’s Role in Healthy Neighborhoods

The Healthy Neighborhoods program developed in a fairly organic way in Milwaukee.

Initially, neighborhood lead organization conducted only a cursory assessment to identify

suitable neighborhoods. Over time, the foundation brought more discipline and analysis to

select the target neighborhoods. In 2012, the foundation and other stakeholders engaged The

Reinvestment Fund to conduct a market value analysis for Milwaukee, a tool described in

the third essay in this volume. As the foundation prepared to redesign the program in 2014,

it used this tool to confirm its designated neighborhoods and identify new middle market

neighborhoods. During this process, the foundation learned the neighborhoods it designated

as “Healthy Neighborhoods” were indeed middle neighborhoods with the exception

of two, which were healthy enough that they graduated from the program.

The foundation’s commitment to middle neighborhoods is evident in the human and

financial capital it has contributed to the program. A program officer provides key leadership,

identifying training needs and appropriate training resources for the lead agencies.

Some of this training has touched on topics such as understanding the Healthy Neighborhoods

approach, branding and marketing, the importance of working with real estate agents

and using LinkedIn, just to name a few.

Since the program’s inception, the foundation has coordinated monthly meetings among

the neighborhood lead agencies. These meetings create synergy, build trust and understanding,

and create a learning community. Neighborhood coordinators come prepared to

share resources and information about upcoming projects, and to collaborate on projects

across neighborhoods. In addition, the program officer identifies and acquires financial

resources, whether from the foundation’s unrestricted funds or by partnering with other

philanthropic entities. An example of unrestricted funds is the foundation’s Model Block

Project. The project provides grants to make the neighborhood more physically attractive

to newcomers and to strengthen social connections among neighbors. Block projects make

an immediate physical improvement or tie closely to a target block strategy. Block projects

involve residents in planning, implementation, and ongoing maintenance.

In commemoration of the foundation’s centennial, the Healthy Neighborhoods Art

Initiative, in partnership with the Greater Milwaukee Foundation Mary L. Nohl Fund,

helped create art in public spaces. The Mary L. Nohl Fund is among the foundation’s

largest funds dedicated to investing in local arts education programs and projects. Five

neighborhoods received more than $80,000. The project was also supported by the Neighborhood

Improvement Development Corporation, which provided matching grants of up

to $20,000.

The Vital Role of Partnerships in Healthy Neighborhoods

None of the work is done in isolation. A critical feature of the program’s success in

strengthening neighborhoods is the large number of partnerships and collaborations. The

foundation has developed relationships with city government, philanthropic partners, and

banks to bring needed capital to the program. One of the foundation’s central partners

is the city of Milwaukee’s Neighborhood Improvement Development Corporation, which

provides eligible homeowners with a forgivable, low interest loan of up to $15,000 through

its Target Investment Neighborhood strategy. In addition, each designated Healthy Neighborhoods

lead agency qualifies for up to $10,000 in matching grants through its Community

Improvement Projects program.

The foundation is one of the founding partners of the Community Development Alliance

(CDA), a consortium of philanthropic and corporate funders that have been working to

align place-based activities and investments in Milwaukee’s neighborhoods since 2010. The

alliance combines resources to make contributions to neighborhood improvement.

The CDA is guided by the belief that successful neighborhood leadership is the key to

neighborhood stabilization and growth. The foundation, along with its community development

philanthropic partners, created two comprehensive leadership programs: The Neighborhood

Leadership Institute (NLI), and the Community Connections Small Grants program.

The NLI develops the skills of neighborhood leaders through a free 10-month program for

neighborhood residents. The program pairs two people who live, work, or volunteer in the

neighborhood. By the end of 2016, more than 60 leaders will have completed the training.

The small grants program also provides support by building social connections. It

provides up to $750 to a group of residents to implement projects that benefit their neighborhood. The review committee is made up of residents, many of whom have participated in

the Neighborhood Leadership Institute. Examples of projects include backyard composting,

family unity craft projects, healthy cooking classes, block parties, positive body image workshops

for young girls, and alley clean ups. This is an example of how partnerships help

enhance the social fabric in neighborhoods.

In 2015, the foundation and Wells Fargo partnered to establish a $1 million pool of

funds to strengthen Milwaukee neighborhoods. A portion of the funds focuses on a targeted

housing preservation strategy that supports homeownership by building equity. The Healthy

Neighborhoods Minor Home Improvement Pilot Program is part of that strategy. It works to

stabilize three designated Healthy Neighborhoods. The program provides matching grants to

homeowners to complete minor exterior home improvement projects.

In summary, both the Baltimore and Milwaukee Healthy Neighborhoods programs have

their roots in the foundation, nonprofit, and neighborhood sectors, and both are showing

genuine progress in strengthening middle neighborhoods. Relative to many other neighborhood

programs, the administrative costs are very small, demonstrating that middle neighborhoods

programs can be very cost-effective.

1. The name “healthy neighborhoods” does not describe a health initiative in the neighborhoods, but rather an

approach to keep the middle neighborhoods strong and vibrant, hence, “healthy.”

Mark Sissman served the Enterprise Foundation for 14 years as president of the Enterprise Social Investment

Corporation (“ESIC”). Under his leadership, ESIC was the nation’s foremost syndicator of

low income housing tax credits. In January 1999 he joined Bank of America as Senior Vice President.

Mr. Sissman was the Deputy Housing Commissioner for Baltimore City. For 11 years Mark Sissman

has served as President of Healthy Neighborhoods, a Baltimore community development intermediary

and CDFI organized by financial institutions, foundations and neighborhood organizations to

improve neighborhoods by increasing home values, rehabilitating homes and marketing neighborhood

assets. Mr. Sissman was President and Chief Executive Officer of the Hippodrome Foundation, the

local partner for the redevelopment of the abandoned Hippodrome Theater, a $70 million, 2,250 seat

world class performing arts center.

Darlene C. Russell brings more than 15 years of nonprofit experience to her role as a foundation

program officer. In addition to participating in the discretionary grant review process, she manages the

Greater Milwaukee Foundation’s Healthy Neighborhoods Initiative and serves on several nonprofit

advisory committees. Prior to joining the Foundation in January 2011, Darlene worked with a

number of organizations to help increase college access to students in the greater Milwaukee area. In her

role as senior outreach consultant at Great Lakes Higher Education Guaranty Corporation she worked

to support low-income first generation college students access post-secondary education by partnering

with nonprofits that helped students and families prepare and pay for college. Darlene graduated with

a bachelor’s degree in community leadership and development from Alverno College and earned a

master’s degree in management from Cardinal Stritch University.