Involuntary part-time employment reached unusually high levels during the last recession and declined only slowly afterward. The speed of the decline was limited because of a combination of two factors: the number of people working part-time due to slack business conditions was declining, and the number of those who could find only part-time work continued to increase until 2013. Involuntary part-time employment recently returned to its pre-recession level but remains slightly elevated relative to historically low unemployment, likely due to structural factors.

While the unemployment rate is the most commonly cited labor market indicator, many economists and policymakers examine a wider array of indicators to gauge the health of the U.S. labor market. One such indicator is the number of people working part-time for economic reasons, often referred to as involuntary part-time employment. These are individuals who work part-time but want to work full-time. A large number of such workers is a sign that the economy is not utilizing its full labor potential.

During the 2007–09 recession, the involuntary part-time employment rate rose to unusually high levels and remained high for some time, even when unemployment fell (Canon, Kudlyak, and Reed 2014 and Valletta, Bengali, and van der List, forthcoming). Policymakers questioned whether the elevated levels represented additional slack in the labor market, which would dissipate in the economic recovery, or a more permanent structural change.

This Letter examines the two opposing forces that contributed to the relatively slow decline of involuntary part-time work after the 2007–09 recession. The number of workers who cited slack business conditions as the reason for involuntarily working part-time increased sharply during the recession and started declining right afterward. In contrast, the number of workers who could not find full-time work increased during the recession, continued to increase throughout the recovery, and did not start to subside until after 2013. This kept the total number of involuntary part-time workers elevated for a few years after the recession’s end, even though the unemployment rate fell steadily.

In 2019, part-time workers for economic reasons as a share of the labor force has returned to its pre-recession level. However, it remains slightly elevated relative to the historically low unemployment rate. Data on worker transitions between involuntary part-time and other types of employment—full-time and voluntary part-time—indicate that the elevation is likely to reflect an ongoing structural change towards more part-time work (Valletta 2018 and Valletta, Bengali, and van der List, forthcoming).

Part-time employment for economic reasons and unemployment

Worker data come from the Current Population Survey (CPS) for January 1994 through September 2019. The CPS classifies each individual into one of five labor force statuses: employed full-time, employed part-time for economic reasons, employed part-time for noneconomic reasons, unemployed, and out of the labor force.

People who work less than 35 hours per week are considered part-time workers. For part-time work to be classified as “for economic reasons,” the worker must desire full-time work and cite as the primary reason for not working full-time one of the following: “slack business conditions,” “could only find part-time work,” or seasonal work. Involuntary part-time workers represent underutilized labor resources or labor market slack. By contrast, workers who are working part-time voluntarily, or for non-economic reasons such as family commitments, generally are not regarded as representing labor market slack.

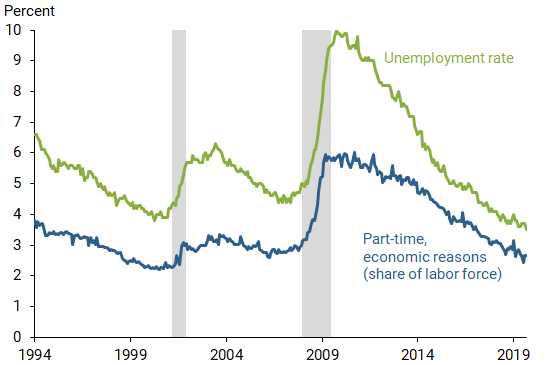

Figure 1 shows involuntary part-time employment as a share of the civilian labor force (blue line). Like unemployment (green line), this series is countercyclical, increasing during recessions and declining during recoveries.

Figure 1

Involuntary part-time workers as a share of the labor force

The series spiked up from 2.7% in 2006 to 5.8% around 2009. It gradually declined, though at a slower pace than the unemployment rate. It dropped to 2.7% on average in the first nine months of 2019.

Two main reasons for involuntary part-time work

Involuntary part-time workers include two main groups. One group cites slack business conditions as the cause for their part-time status. This typically refers to workers whose shifts have been cut from full-time to part-time. This group tends to reflect cyclical variation, meaning it increases sharply during recessions and starts declining immediately once recovery begins.

Another group includes those who cite being able to only find a part-time job as the reason for working part-time. In contrast to the first group, the number of workers who can only find part-time jobs increases during a recession and continues to increase throughout the recovery as more job openings are posted. This component can reflect both cyclical and structural factors. For example, if the economy experiences structural shifts in the composition of jobs toward less full-time work being available, this component might increase.

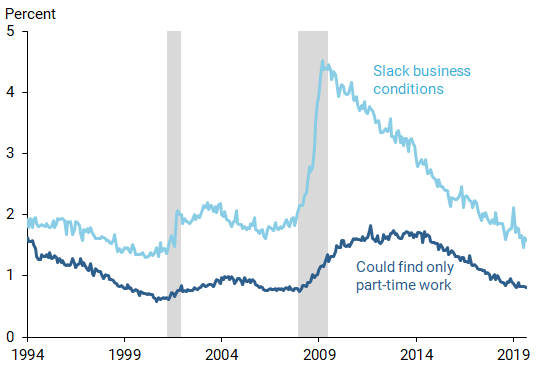

Figure 2 shows these two main components of involuntary part-time work as shares of the labor force. Two opposing forces shown in the figure contributed to the relatively slow return of involuntary part-time work to its pre-recession level in the initial years of the recovery from the 2007–09 recession.

Figure 2

Two main reasons for involuntary part-time work status

The portion caused by slack business conditions (light blue line) reached its peak of 4.3% in 2009 and started steadily declining immediately afterward. It recently fell to 1.7%, which is lower than its pre-recession low of 1.8% in 2006.

In contrast, involuntary part-time employment due to inability to find full-time work (dark blue line) increased from 2009 to 2013 and started slowly declining only after 2013. In part, this reflected the severity of the recession: as the economy started recovering from the recession, many of the jobs that were created were part-time due to heightened uncertainty among businesses. Consequently, after the 2007–09 recession, the number of workers who cited being able to find only a part-time job continued to increase well into the recovery.

The second group kept the total number of involuntary part-time workers elevated for a few years after the recession’s trough, even when the unemployment rate was steadily falling.

Transitions from and to working part-time for economic reasons

Households in the CPS are surveyed for a few consecutive months. This allows an individual’s responses to be merged month-to-month to show transition rates between the five labor status groups: employed full-time, employed part-time for economic reasons, employed part-time for non-economic reasons, unemployed, and out of the labor force.

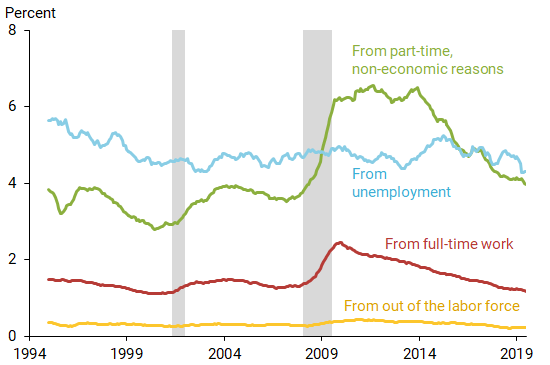

Figure 3 shows the transition rates to part-time work for economic reasons from the other four labor market statuses. During the 2007–09 recession, there was a substantial increase in the transition rates from full-time employment (red line) and from voluntary part-time employment (green line). By 2019, those rates declined. The transition rate from full-time employment, which reflects cyclical variation, has returned to its pre-recession level. However, the transition rate from voluntary part-time employment, which reflects the inability to find full-time work, is still slightly higher than before the recession and well above its level from the early 2000s.

Figure 3

Probability of transitioning to involuntary part-time status

Source: Author’s calculations from CPS microdata, January 1994 to July 2019.

The elevated rate of transitions from voluntary to involuntary part-time work indicates that structural factors are in play. It suggests that workers are not able to find full-time work. Its elevation is consistent with recent literature that argues that structural shifts in the economy have made full-time work more scarce than before (Valletta, Bengali, and van der List, forthcoming).

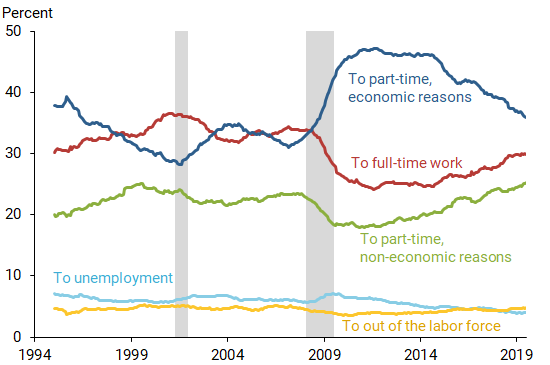

Figure 4 shows the transition rates from involuntary part-time work to the four other labor market statuses as well as the rate of people who remain in this status over time (dark blue line). The probability of remaining involuntarily part-time employed increased substantially during the recession. It has declined since but remains elevated. That is, workers have become stuck in involuntary part-time jobs for longer periods.

Figure 4

Probability of transitioning from involuntary part-time status

Source: Author’s calculations from CPS microdata, January 1994 to July 2019.

Similar to the transition rates to involuntary part-time work, Figure 4 shows a substantial cyclical variation in transition rates from this status to other types of employment. During the recession, transition rates from part-time to full-time employment (red line) and to voluntary part-time employment (green line) declined substantially. As of 2019, the transition rate to full-time employment still remains below its pre-recession level and is even further below its level from the early 2000s. This might be another indicator that full-time work has become more scarce. In contrast, the transition rate to voluntary part-time employment has recovered and exceeded its pre-recession level.

Figures 3 and 4 also show that the cyclical movements of the transition rates between involuntary part-time work and non-employment are much smaller than the movements in the transition rates for other types of employment. The changes in the transition rates to and from involuntary part-time work during and after the 2007–09 recession were associated with changes in the number of full-time employed and voluntary and involuntary part-time employed, but not with changes in unemployment or the number of people out of the labor force (Canon et al. 2015, Warren 2017, and Borowczyk-Martins and Lalé 2019).

Conclusion

This Letter examines part-time employment for economic reasons a decade after the 2007–09 recession. In 2019, this group constitutes 2.7% of the labor force, a substantial decline from its peak of 5.8% in 2009. At the beginning of the recovery, this rate remained high because, as the number of part-time workers due to slack business conditions was declining, the number working part-time because they could only find part-time work continued to increase well into the recovery.

In 2019, the involuntary part-time rate returned to its pre-recession rate. It remains slightly elevated relative to an unemployment rate that is near its historical low. Examining detailed worker transitions between involuntary part-time work and other types of employment—full-time and voluntary part-time—indicates that this elevation is due to the inability to find full-time jobs and is likely to reflect an ongoing structural change.

Marianna Kudlyak is a Research Advisor in the Economic Research Department of the Federal Reserve Bank of San Francisco.

References

Borowczyk-Martins, Daniel, and Etienne Lalé. 2019. “Employment Adjustment and Part-Time Work: Lessons from the United States and the United Kingdom.” American Economic Journal: Macroeconomics 11(1), pp. 389–435.

Canon, Maria, Marianna Kudlyak, and Marisa Reed. 2014. “Is Involuntary Part-Time Employment Different after the Great Recession?” FRB St. Louis Regional Economist, July.

Canon, Maria E., Marianna Kudlyak, Guannan Luo, and Marisa Reed. 2014. “Flows To and From Working Part-Time for Economic Reasons and the Labor Market Aggregates During and After the 2007–09 Recession.” FRB Richmond Economic Quarterly, 2014:Q2.

Valletta, Robert G., Leila Bengali, and Catherine van der List. Forthcoming. “Cyclical and Market Determinants of Involuntary Part-Time Employment.” Journal of Labor Economics. Available as FRB San Francisco Working Paper 2015-19.

Valletta, Robert G. 2018. “Involuntary Part-Time Work: Yes, Here to Stay,” SF Fed Blog, April 11.

Warren, Lawrence F. 2017. “Part-Time Employment and Firm-Level Labor Demand over the Business Cycle.” Center for Economic Studies, U.S. Census Bureau, unpublished manuscript.

Opinions expressed in FRBSF Economic Letter do not necessarily reflect the views of the management of the Federal Reserve Bank of San Francisco or of the Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System. This publication is edited by Anita Todd and Karen Barnes. Permission to reprint portions of articles or whole articles must be obtained in writing. Please send editorial comments and requests for reprint permission to research.library@sf.frb.org