Rob Valletta, vice president at the Federal Reserve Bank of San Francisco, stated his views on the current economy and the outlook as of June 14, 2018.

- The U.S. economy remains on a solid growth path. Sustained strengthening of employment opportunities and consequent gains in household income have been fueling consistent growth in consumer spending. This in turn is supporting business expansion plans and further employment gains, creating a virtuous cycle of economic growth.

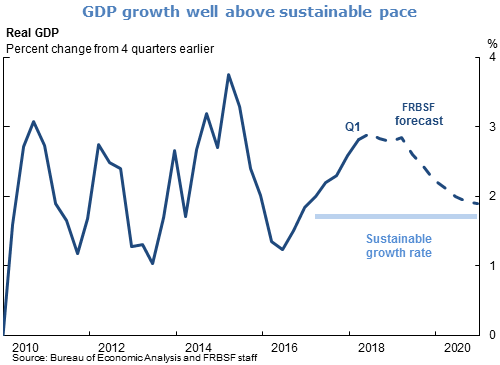

- The pace of real GDP growth has been on an upward trajectory in recent quarters. The economy grew 2.8% between the first quarters of 2017 and 2018, well above the 2.2% average pace of growth since the expansion began in mid-2009. We expect this pace to continue in 2018.

- The key tailwind propelling growth is federal fiscal stimulus. With the waning effects of this stimulus over the next few years and the expected tightening of financial conditions, we project that growth will slow to our estimated sustainable pace of just under 2% by 2020.

- If the current expansion continues past June 2019, it will be the longest in business cycle records dating back to the mid-1800s. The risks of stiffening headwinds remain, notably from rising tensions over international trade, but they are unlikely to be severe enough to push the expansion off course.

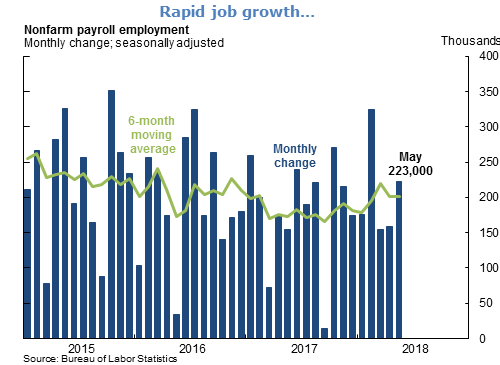

- Recent payroll employment gains have been uneven but strong on balance, averaging a touch over 200,000 jobs per month for the past six months. This is somewhat below the very rapid pace seen in 2014 and 2015 but approximately double the pace needed to maintain a vibrant labor market.

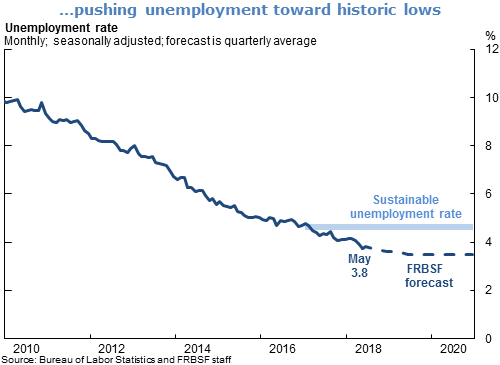

- Employment gains have continued to push the unemployment rate down toward historical lows. May’s rate of 3.8% equals the low recorded at the end of the strong expansion in the 1990s. We expect unemployment to drop to 3.5% next year and stay there through 2020. This is well below our estimate of 4.6% for its sustainable level over the long term and essentially matches lows not seen since the late 1960s.

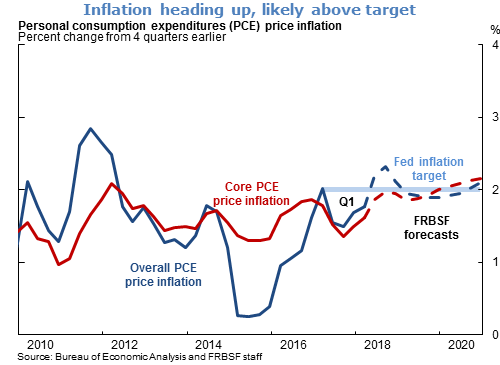

- Price inflation has taken a decided turn back toward the Fed’s 2% objective over the past two quarters. With continued above-trend growth and tightening constraints on labor and other resources, we expect inflation to rise further and slightly overshoot the 2% target in 2020.

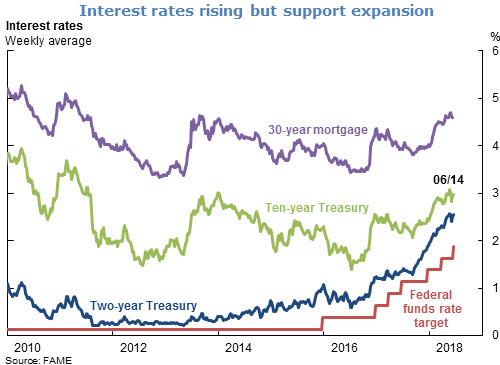

- Following the conclusion of its latest meeting on June 13, the Federal Open Market Committee (FOMC) announced its decision to raise the federal funds rate by one-quarter percentage point to the new target range of 1¾ to 2%. The Committee highlighted the favorable outlook for employment and inflation in support of its decision and noted expectations of further gradual rate increases. Rates on Treasury securities and residential mortgage loans generally have been rising along with policy rates over the past few years but remain low by historical standards, providing continued support to the expansion.

- Although the low unemployment rate and other indicators portray a labor market that is very strong relative to previous expansions, longer-term changes in the labor market have been contributing to an evolving mix of challenges and opportunities for workers.

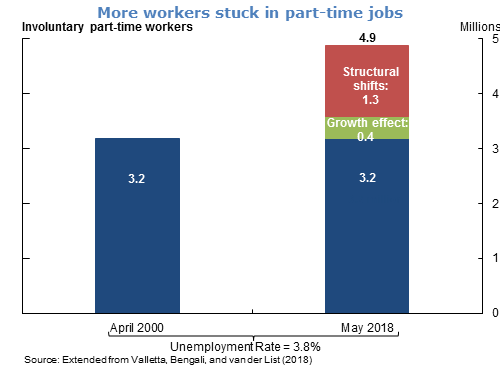

- One notable trend in recent years is the rising number of involuntary part-time (IPT) workers, defined as individuals who prefer full-time jobs but are only able to obtain jobs with part-time hours. In May 2018, there were nearly 5 million IPT workers, compared with 3.2 million the last time the unemployment rate was 3.8%, in April 2000. A small portion of the increase simply reflects the growth in overall employment. However, recent research indicates that most of the rise in IPT work is attributable to persistent structural changes in the labor market, mainly the shift toward service industries such as restaurants and hotels, where part-time work is common.

- The rise in IPT work has been accompanied by a perceived increase in the incidence of nontraditional paid work arrangements, focusing on independent work with flexible or uneven hours, broadly referred to as the “gig economy.” This includes relatively new modes of work that rely on computer applications, such as for ride-hailing and online task assignments, as well as more traditional informal paid positions, such as childcare and housecleaning.

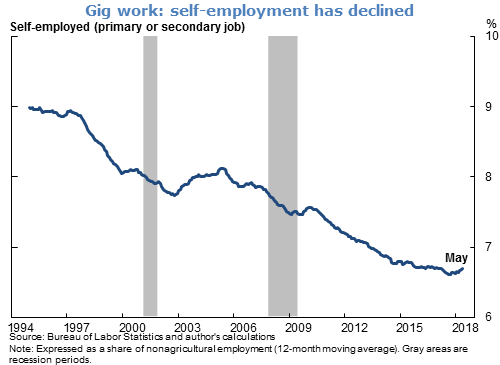

- Consistent with its informal underpinnings, the rise of the gig economy does not show up in traditional measures of labor market activity. Gig work is a form of irregular self-employment. However, the incidence of self-employment in primary or secondary jobs has been declining rather than rising, calculated using data from the Bureau of Labor Statistics’ (BLS) monthly household survey.

- Recent survey results further identify the size and contours of the gig economy. The sources include a revived BLS survey of alternative and contingent employment and a recent Federal Reserve Board survey of household well-being. These surveys suggest less expansion in the overall incidence of gig work than is commonly believed, with very limited hours and earnings derived from gig jobs. This pattern of limited and sporadic gig work has been confirmed by other studies that rely on tax records, online transactions, and banking records.

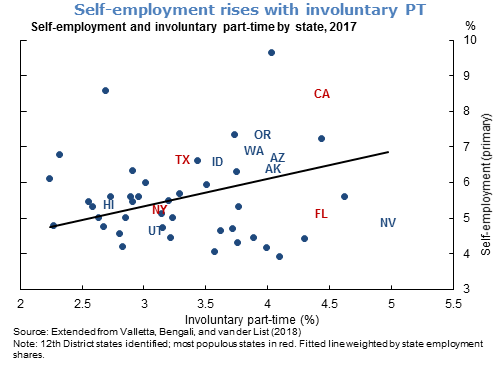

- Despite its small scope, gig work appears to be connected to the rise in IPT work. States with higher IPT rates tend to have higher rates of self-employment as well, suggesting that gig work may in part be a response to structural shifts in the types of jobs and work schedules that are available or desired.

The views expressed are those of the author, with input from the forecasting staff of the Federal Reserve Bank of San Francisco. They are not intended to represent the views of others within the Bank or within the Federal Reserve System. FedViews appears eight times a year, generally around the middle of the month. Please send editorial comments to Research Library.