In short, the answer to your question is “yes.” In this column I will focus on describing how the 2008 buildup in bank reserve holdings is related to actions taken by the Federal Reserve in response to the severe financial crisis. The full story about what the increase in reserves means for the economy and monetary policy will have to wait for my upcoming columns. To get started, let me provide a quick refresher on bank reserves.

A quick review of bank reserves

In the U.S., all depository institutions (DIs) must retain a percentage of certain deposits to be held as reserves. The Federal Reserve (Fed) sets reserve requirements.1 Central banks in other nations have similar legal requirements for holding reserves against deposits.2 Reserves might be held as vault cash or in accounts at the Fed. Currently most of the DIs’ reserves are held in accounts with the Fed (directly or indirectly through another bank).

Any holdings of reserves by DIs above their required levels are called excess reserves. Traditionally (before October 2008), DIs held some excess reserves to deal with short-term cash flow uncertainties, such as unexpectedly large depositor withdrawals. However, up until recently excess reserves held with the Fed did not earn interest so DIs had an incentive to minimize their holdings of excess reserves.

What is the magnitude of the recent buildup of excess bank reserves?

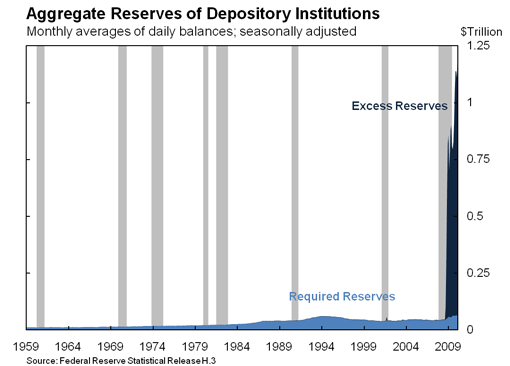

Let’s start by taking a quick look at the accounting of changes in the Fed’s balance sheet. When the Fed makes loans or buys assets, it creates both an asset on its balance sheet (loans and securities) and a deposit liability (reserves). For example, since June 2007 the combined magnitude of Fed direct lending programs and asset purchases (other than Treasuries) added about $1.3 trillion to Fed assets. When the Fed made the loans and paid for the assets it purchased, it credited banks’ reserve accounts (i.e. created a Fed liability). During this period, deposits at the Fed, including both bank and the U.S. Treasury deposits, also increased by about $1.3 trillion. Excess reserves, shown in Chart 1, rose by over $1 trillion.

Chart 1

Let’s look at the link between the Fed’s actions and the excess reserve buildup in more detail.

What is the link between this recent reserve buildup and monetary policy?

The Federal Reserve responded aggressively to the financial crisis that emerged in the summer of 2007. The response began with the conventional tools of monetary policy: a discount rate cut in August 17, 2007, followed by a decision to lower the target for the federal funds rate by 50 basis points (to 4-3/4 percent) on September 18, 2007. To further stimulate the weakening economy during this first year of the crisis, the Federal Open Market Committee (FOMC) proceeded to lower the federal funds target rate in subsequent meetings.

Moving beyond these traditional tools of monetary policy, the Federal Reserve responded to the unusual stress in the financial markets with some new or unconventional tools. The Term Auction Facility (TAF) — the first of a number of new liquidity and credit facilities designed to provide credit to financial institutions and financial markets — was introduced in December 2007, and additional facilities were opened in March 2008. As a result of these actions, the composition of the Federal Reserve balance sheet began to change.

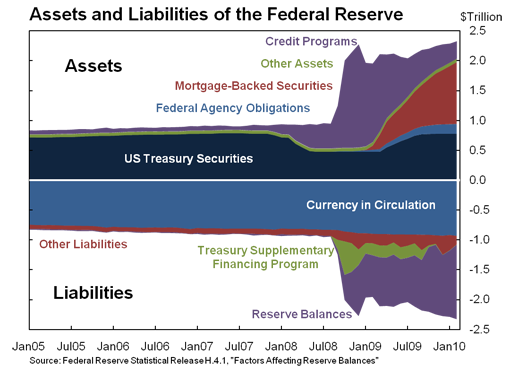

In the fall of 2008, as financial market conditions were deteriorating rapidly and the fed funds target rate was being reduced towards its ultimate low (zero to 25 basis point range), the Fed took extraordinary actions that caused its balance sheet to dramatically increase in size and that made major changes in the composition of the Fed’s assets. As shown in the top panel of Chart 2, the increase was originally driven by the credit program expansion but was later dominated by the Fed purchases of mortgage backed securities (MBSs), agency related debt, and longer-term Treasury securities. This marked the shift of monetary policy into unchartered waters that many refer to as “quantitative easing.“3 Quantitative easing is commonly defined as the policy strategy of seeking to reduce long-term interest rates by buying large quantities of longer-term financial assets to stimulate the economy when the overnight rate has already been lowered to near zero (see Bullard 2010 ).

Chart 2

The focus of the unconventional policy response during the depth of the crisis was on the mix of loans and securities that the Fed holds as assets and the effect of these shifts in the Fed’s balance sheet composition on credit conditions for households and businesses. As highlighted by Chairman Bernanke, in the challenging economic environment when these policy actions were undertaken, one dollar of longer-term securities purchase is likely to have a different impact on the economy than one dollar of lending to banks or one dollar of lending to support the commercial paper market. Due to these differences in the impact of various lending types on the economy, it is not easy to summarize the policy stance by a single number such as the quantity of excess reserves.

As I pointed out earlier, the expansion of the asset side (making direct loans and purchasing long-term securities) of the Fed’s balance sheet was accompanied by increases in the reserves at depository institutions (Fed liabilities). The bottom panel of Chart 2 shows changes in liabilities that accompanied the expansion of the asset side of the Fed’s balance sheet. 4

In October 2008 an important policy change took place — the Fed began paying interest on reserves.5 Recall that prior to this policy change, depository institutions had little incentive to hold excess reserves, since those reserves earned no interest. By paying an interest rate that fluctuates with the fed funds target (its primary monetary policy tool)6, the Federal Reserve has been able to change this incentive. The ability to pay interest on reserves has given the Federal Reserve better control over short-term interest rates, including the ability to raise the interest rate on reserves to provide an incentive for DIs to hold the funds at the Fed when the Fed funds target rate is increased.7

With the unconventional policy impact coming from the asset side of the Fed balance sheet (direct lending and asset purchases), the increase in excess reserves should be seen as a by-product (rather than the focus) of the policy action. This contrasts sharply with conventional policy easing, when the Fed injects reserves to lower the fed funds rate and (indirectly) other interest rates when easing. In the latter case, the impact of policy comes from the supply of reserves (that is the Fed’s liabilities).

Bank reserves for the system as a whole are determined by the central bank

One last important point I want to make is that the overall level of bank reserves in the banking system is determined by the Federal Reserve. While it is true that an individual bank may decrease its excess reserves by making loans, that does not hold true for the banking system as a whole. Keister and McAndrews put it this way in a Federal Reserve Bank of New York Staff Report (No. 380, July 2009):

The general idea here should be clear: while an individual bank may be able to decrease the level of reserves it holds by lending to firms and/or households, the same is not true of the banking system as a whole. No matter how many times the funds are lent out by the banks, used for purchases, etc., total reserves in the banking system do not change. The quantity of reserves is determined almost entirely by the central bank’s actions, and in no way reflect the lending behavior of banks.

Conclusion

Indeed, the rise in excess reserves that you observed is related to the Fed’s policy actions. However, the link between policy actions and excess reserves is very different from what happens in a conventional policy response when the Fed was not paying interest on reserves. With the unconventional monetary policy response used by the Fed in the recent economic downturn, it is important to think about the policy effect as coming from the asset side of the balance sheet, rather than from the increase in reserves.

While I have explained the link between excess reserves and monetary policy, I have not addressed two important questions that arise when one thinks about excess reserves: (1) does the buildup of excess reserves indicate that the Federal Reserve has not been able to stimulate lending?; and (2) will this large quantity of excess reserves cause future inflation? The short answer to these questions would be, respectively, “no” and “not necessarily.” However, since these are such important issues that warrant further explanation, I will tackle both of them in upcoming Dr. Econ columns. Stay tuned!

For more information on the financial crisis, the Fed’s monetary policy response, and the recovery, please see the Federal Reserve Bank of San Francisco website, The Economy: Crisis & Response.

For more reading on the causes and consequences of growing excess bank reserves, see:

Carlstrom, Charles T. and Timothy S. Fuerst. Monetary Policy in a World with Interest on Reserves. Federal Reserve Bank of Cleveland, Economic Commentary, June 10, 2010.

Keister, Todd and James J. McAndrews. “Why Are Banks Holding So Many Excess Reserves?” Federal Reserve Bank of New York Current Issues in Economics and Finance, vol. 15, Number 8.

For more on Federal Reserve statistical releases, see:

Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System. Factors Affecting Reserve Balances.

Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System. Aggregate Reserves of Depository Institutions and the Monetary Base.

Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System. Credit and Liquidity Programs and the Balance Sheet.

End Notes

1. More on Reserve Requirements set by the Federal Reserve.

2. Note, legal requirements for reserves against deposits are different from the allowance for loan and lease losses, also sometimes described as loan loss reserves. See Office of the Comptroller of the Currency, Allowance for Loan and Lease Losses (1998), page 1.

3. Note that Chairman Bernanke called it “credit easing” (to highlight the differences between the policy approach used by the Bank of Japan from 2001 to 2006).

4. Initially, the Treasury’s Supplementary Financial Program was introduced to reabsorb the reserves created (Please see Haubrich and Lindner 2009 for further discussion of this program).

5. More on this policy change.

6. More information.