Workers age 55 and older left the labor force in large numbers following the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic. Four years later, participation within this age group has yet to return to pre-pandemic levels, despite the strongest labor market in decades. This has resulted in an estimated shortfall of nearly 2 million workers. Analysis shows that the participation shortfall is concentrated among workers in this age group without a college degree and can be explained by increased and growing retirement rates for this group, above pre-pandemic trends.

A strong labor market is usually an engine that pulls and keeps people in the labor market, growing the pool of available workers. These forces have played out over the past three years for many groups of people, with one notable exception: workers age 55 and older. In contrast to other age groups, workers age 55 and older have yet to reverse the decline in labor market participation that occurred with the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic. By some estimates, this represents about 2 million workers who otherwise would have been in the labor force in 2023 absent the global pandemic.

This Economic Letter investigates the drivers of recent trends in labor force participation among workers age 55 and older, particularly the divergence across levels of educational attainment. We find that the bulk of the participation shortfall for this age group is concentrated among workers without a college degree, while participation among college-educated workers is currently at its pre-pandemic trend. The difference can be explained by increased retirement rates among workers without a college degree. Retirements among this group increased significantly at the onset of COVID. Moreover, the increased rate of retirement for these workers has not only continued well into the full reopening of the economy and strong economic expansion, but it also appears to have accelerated somewhat over the past two years.

Labor force participation following the onset of COVID-19 pandemic

The arrival and spread of COVID-19 exposed people age 55 and older to greater health risks than younger populations faced. Rates of severe symptoms and hospitalization before the availability of vaccines were estimated to be four to six times greater for this group compared with the general population. This fact is most likely to have induced strong and persistent changes in behavior. People ages 55 and older reported higher rates of social distancing and other mitigation behaviors, both during the initial onset of the pandemic and after its peak (Hutchins et al. 2020). Moreover, measures of anxiety and fear rose more among older populations and remained elevated well after vaccines were widely available and social activities progressively resumed (Hadjistavropoulosa and Asmundsona 2022).

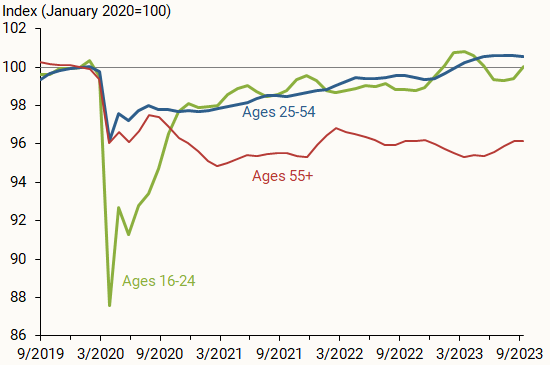

This social context provides some clues into the reasons for the very persistent declines in labor force participation among people age 55 and older since March 2020 (see Goda et al. 2023). Figure 1 plots labor force participation (LFP) rates for major age groups between September 2019 and the latest available Current Population Survey data from the Bureau of Labor Statistics. The figure adjusts the participation rates for each group to equal 100 in January 2020 for ease of comparison, as LFP rates vary significantly across age groups. The rates are typically around 56% for young workers between ages 16 and 24, compared with 83% for prime-age workers between ages 25 and 54, and around 40% for older workers age 55 and over.

Figure 1

Rates of labor force participation by age group: 2020=100

Source: Bureau of Labor Statistics and authors’ calculations.

Young workers (green line) experienced the largest decline in participation at the onset of the pandemic, quickly falling 13% relative to their participation rate in January 2020. The decline for prime-age workers, though still large, was more muted (blue line). Their participation rate in the labor market fell 3.6% relative to January 2020. Among older workers (red line), the decline in participation was somewhat more significant, with a 5% drop following the onset of the pandemic.

However, following widespread vaccinations and a broad reopening of the economy through 2021, labor market participation for workers age 55 and older not only failed to recover but declined even further. After an initial rebound echoing that of other age groups during the summer of 2020, participation for those 55 and over declined again through the fall as new waves of infections spread across the country, and finally reached a low point in March 2021.

Now, a couple of years into the reopening and normalization of the economy, the situation remains much the same: the participation rate for workers age 55 and older has essentially not moved, hovering around 38.5%, nearly 2 percentage points below their pre-COVID rate. This stands in stark contrast with the full recovery for workers in other age groups.

The changing trends along education lines

Before the pandemic, the rate of participation in the labor market for workers age 55 and older had remained fairly stable since 2012, at around 40%. At the onset of the pandemic, the rate abruptly stepped down to a new lower level, with no indication that workers would return to prior levels of active participation in the labor market. This description, however, masks a significant difference across this age group according to workers’ level of educational attainment.

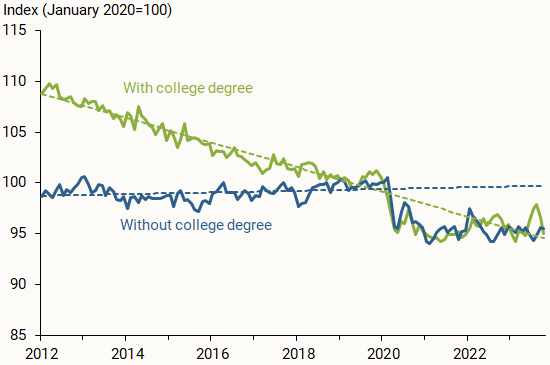

Looking at participation rates for individuals age 55 and older with and without a college degree reveals very different trends in the decade leading up to the pandemic. Figure 2 adjusts the rates of the two groups to 100 in January 2020 for ease of comparison. The participation rate for those without a college degree was essentially constant between 2012 and 2019 (blue line). Participation among individuals with a college degree in this age group has been on a downward trend over the same period (green line). The dashed lines show the distinct pre-pandemic linear trends in participation for these two groups, estimated from the data between 2012 and 2019.

Figure 2

Labor participation for workers age 55+ by education

Source: Bureau of Labor Statistics and authors’ calculations.

Taking the pre-existing trends into account exposes very different lasting effects of the pandemic on these two groups. The drop in labor force participation for individuals without a college degree is a break from what would have been expected following the pre-COVID trend. This contrasts with the experience for college-educated workers, whose rate of participation in the labor market in 2023 returned to its pre-pandemic trend. In this sense, understanding any labor force participation shortfall among workers age 55 and older requires focusing on the decisions made by individuals without a college degree.

Workers without college degrees appear to be driving the rise in retirements

Early studies into the lower participation rates among older workers during the recovery from the pandemic recession focused on evidence of greater movements into retirement than are typically observed and would have been predicted (Montes et al. 2022). That is, the rate of retirement significantly and persistently exceeded what pre-COVID patterns would have suggested.

To get a sense of how significant this jump in retirements is for overall labor force participation, we consider what the rate of retirement likely would have been without the pandemic. We compare actual retirements with projected rates based on the rate of increase in the retirement share averaged over 2012 to 2019 (not shown). The gap between actual retirements and this pre-pandemic trend scenario represents 2 million workers who would have been in the labor market if the pandemic had not happened.

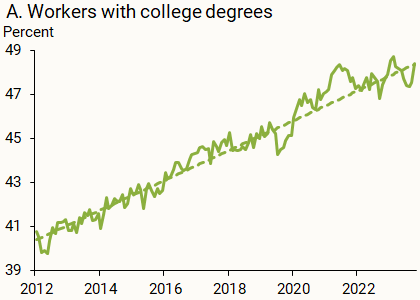

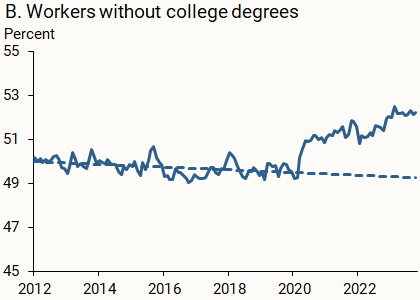

Looking deeper into the data reveals a distinct pattern to the shift in retirement behavior by level of education. The data in Figure 3 show that nearly all the surge in retirements around the arrival of COVID-19 is explained by the behavior of people age 55 and older without a college degree. Panel A shows that the retirement share of the population age 55 and older with a college degree approximately tracks a projection based on its pre-pandemic trend. However, the share for individuals without a college degree shown in panel B jumped from about 49% to 51% at the onset of the pandemic. Moreover, it appears to have continued increasing and diverging from its pre-pandemic trend since then. This share reached 52.2% near the end of 2023, well above the 49.3% projected from the pre-pandemic trend.

Figure 3

Share of the population age 55 and older who report being retired

Note: Dotted lines are linear trends estimated on 2012-2019 data.

Source: Bureau of Labor Statistics and authors’ calculations.

A further breakdown of the data (not shown) reveals that this rising share of retirements among workers without a college degree age 55 and older is similar across men and women and is concentrated among white individuals. The shares of retirements in 2023 among Hispanic and Black workers approximately align with their respective pre-pandemic trends. Other research suggests that this may be due to higher wealth saved for retirement among White workers compared with workers of other races and ethnicities, in combination with the safety and physical concerns associated with the occupations of workers without college degrees (Montes et al. 2022).

Conclusion

The differences in retirement decisions since the pandemic between workers with and without a college degree has implications for potential growth in the labor force going forward. If current retirement trends among individuals without a college degree were to reverse, we could see additional growth in workers age 55 and older joining the labor market, providing additional relief to an already tight labor market. If this does not occur, the economy will need to draw in workers from other age groups to accommodate the increased demand for labor. This has been the case over the past couple of years: growth in labor force participation among workers between ages 25 and 54 has outpaced pre-pandemic trends, significantly expanding the number of workers available to fill the plentiful job vacancies in the economy (Prabhakar and Valletta 2024).

References

Goda, Gopi Shah, Emilie Jackson, Lauren Hersch Nicholas, and Sarah See Stith. 2023. “The Impact of COVID-19 on Older Workers’ Employment and Social Security Spillovers.” Journal of Population Economics 36(2), pp. 813–846.

Hadjistavropoulos, Thomas, and Gordon J.G. Asmundson. 2022. “COVID Stress in Older Adults: Considerations during the Omicron Wave and Beyond.” Journal of Anxiety Disorders 86(102535).

Hutchins, Helena J., Brent Wolff, Rebecca Leeb, Jean Y. Ko, Erika Odom, Joe Willey, Allison Friedman, and Rebecca H. Bitsko. 2020. “COVID-19 Mitigation Behaviors by Age Group—United States, April–June 2020.” Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report 69(43), pp. 1,584–1,590.

Montes, Joshua, Christopher Smith, and Juliana Dajon. 2022. “The ‘Great Retirement Boom’: The Pandemic-Era Surge in Retirements and Implications for Future Labor Force Participation.” Finance and Economics Discussion Series 2022-081, Federal Reserve Board of Governors.

Prabhakar, Deepika Baskar, and Robert G. Valletta. 2024. “Why Is Prime-Age Labor Force Participation So High?” FRBSF Economic Letter 2024-03 (February 5).

Graduate Student, Princeton University

Opinions expressed in FRBSF Economic Letter do not necessarily reflect the views of the management of the Federal Reserve Bank of San Francisco or of the Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System. This publication is edited by Anita Todd and Karen Barnes. Permission to reprint portions of articles or whole articles must be obtained in writing. Please send editorial comments and requests for reprint permission to research.library@sf.frb.org