A range of tariffs on U.S. imports has been enacted or considered recently. Trade tariffs can potentially affect price inflation for consumption and investment goods. Estimates suggest that the impact on prices for investment goods is likely to be much larger than for consumption goods. For example, if an across-the-board 25% tariff is fully passed through to finished goods, near-term price increases are estimated to be about 9.5% for investment goods and 2.2% for consumption goods. These price increases for investment goods can have important implications for businesses’ investment decisions.

Download replication data zip file (87 MB)

Since early this year, the United States has enacted or considered a wide range of import tariffs against their many trade partners. Tariffs are levied on imported goods that are either directly sold to U.S. consumers, used as intermediate goods and processed further in the United States, or used as equipment for the production of U.S. goods and services. How much this will affect domestic prices overall will depend on a range of factors, including how much imports contribute to the prices of consumption, intermediate, and investment goods, and how businesses and consumers ultimately respond to these changes.

In this Economic Letter, we assess the direct effect that import tariffs may have on U.S. inflation in the near term. To do so, we combine the most recent data on the foreign import content of U.S. consumption and investment spending with corresponding price data, which we use to calculate the potential impact of tariffs on price inflation of consumption and production goods.

We focus on near-term direct effects and do not account for adjustments to supply, markups, or responses of importers, domestic producers, consumers, and policymakers. With that caveat, our estimates suggest that the impact of an across-the-board 25% tariff could be much larger on investment goods prices, about 9.5%, than on consumption goods, about 2.2%. These effects could have important implications for domestic production costs and businesses’ investment decisions.

Tariffs over time

The United States has relied on tariffs on a variety of imported items to various extents throughout its history. Tariffs are a tax on traded items, typically on imported goods, and their costs are likely to affect prices of goods and services and overall spending for those items. Therefore, changes to tariffs can have an impact on overall inflation faced by consumers and businesses.

A tariff on all goods from Mexico, for example, is likely to affect prices of both goods purchased by consumers and goods used in the production process. Such a tariff would affect consumers through costs of imported food. Similarly, it could affect U.S. businesses through production costs for items such as medical equipment.

When assessing how much a tariff might impact U.S. spending, production costs, and prices, the first step is to consider how much of these costs can be traced back to imports. A second important step is to consider how much that consumption or investment good contributes to overall inflation.

Import content of consumption spending

Most U.S. shoppers are used to seeing a sizable variety of imported items online and in stores labeled as “made in” some other country. However, despite that shopping experience, the United States remains a relatively closed economy. In fact, the vast majority of goods and services sold in the United States are produced domestically. In 2024, for example, imports corresponded to about 14% of U.S. GDP.

These raw statistics on trade do not exactly reflect how much U.S. households and businesses spend on imports, though (Hale and Hobijn 2011; Hale et al. 2019a,b; and Barbiero and Stein 2025). One reason is that the selling price of items labeled as made in a foreign country also reflects value added domestically, such as costs of transportation within the United States, wholesale and retail activities, and associated markups. Second, goods that are labeled and sold as “Made in the USA” often include imported parts in their production; therefore, a share of their prices reflects value added abroad.

To calculate how changes to tariffs affect spending costs and contribute to inflation in the United States, we first need to calculate how much of overall U.S. consumption spending can be traced back to value added abroad, that is, the import content of spending. Therefore, this calculation must subtract the U.S. content of goods made elsewhere and add the import content of U.S.-produced goods to the raw measure of U.S. expenses on imports.

For this calculation, we combine data from the Bureau of Economic Analysis’ 2023 input-output matrix and the Census Bureau U.S. International 2023 Trade Data. The former contains information on final and intermediate goods sold and used in the United States. The latter contains information on where imported items originated.

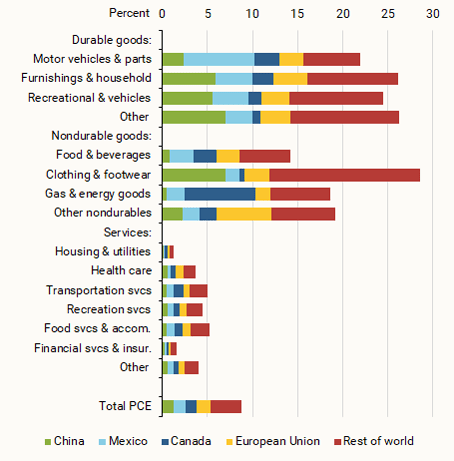

We first calculate U.S. consumption goods import content by major U.S. trade partners and the rest of the world (for details, see Hale et al. 2019a,b). Figure 1 reports the import content of personal consumption expenditures (PCE) categories for imports from China, Mexico, Canada, and the European Union—some of the largest U.S. importing regions—and the rest of the world.

Figure 1

Goods import content by personal consumption expenditures

The sections of each bar in Figure 1 show the share of U.S. goods consumption that can be traced back to imports from each economic region. For example, focusing on motor vehicles and parts, nearly 8% of U.S. consumption spending can be traced back to imports from Mexico. Overall, about 22% of consumption spending in this category goes toward imports. Similarly, nearly 7% of U.S. household consumption of clothing and footwear can be traced back to imports from China. Note that even in categories with high shares of import content such as clothing and footwear, the import content is about 30%, meaning that about 70% of spending on clothing and shoes are retained domestically. This is because the bulk of costs associated with these items reflect domestic costs, such as transportation, and markups.

The bottom bar in Figure 1 shows that once we weight the import content in PCE categories by the category’s share in PCE and add up the results, about 9% of overall PCE for consumption goods can be traced back to goods imports.

Import content of investment spending

Similar to our calculations for consumption spending categories, we can calculate the import content of different types of equipment used in U.S. production processes. By contrast with consumer goods sold by businesses directly to consumers, investment goods are typically purchased by businesses and used for production.

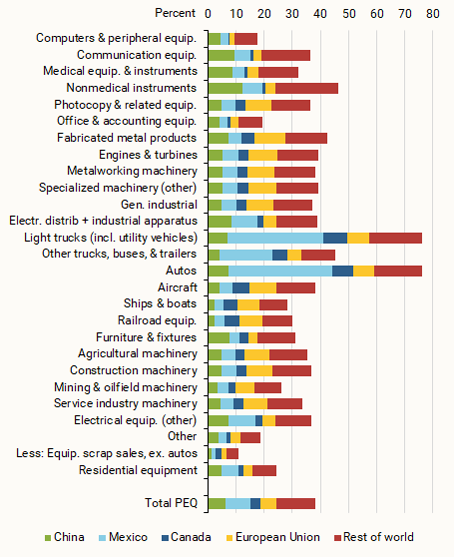

Figure 2 reports the results from applying our calculations for categories of private investment in equipment (PEQ). For example, the share of autos in PEQ that can be traced back to imports nears 75%, with imports from Mexico contributing 37%. Overall, the bottom bar on Figure 2 shows that, after weighting by PEQ categories’ shares and adding up the results, about 38% of the total cost of investment goods can be traced back to imports.

Figure 2

Goods import content by private investment in equipment

The import content is much larger for investment goods than for consumption goods. This is because domestic markups tend to be smaller for investment goods than for consumer goods, making the import content of their costs much larger.

Effects of tariffs on prices

How much tariffs on consumption and investment goods ultimately affect inflation will depend, among other things, on the import content of these goods and on their contributions to their respective price index.

Estimates as of April 15 of the effects of the latest trade policy announcements suggest an average tariff rate near 25% (Yale Budget Lab 2025). Although this rate may vary by country, for simplicity, we estimate the potential effects on consumption and investment goods prices from a 25% tariff applied to all imported goods from each of the five economic regions in Figures 1 and 2. In our calculations, we make two important assumptions. First, we assume that tariffs are fully passed to U.S. consumer and business prices. Second, we focus on near-term direct effects and do not account for adjustments to the supply, markups, or responses of importers, domestic producers, consumers, and policymakers.

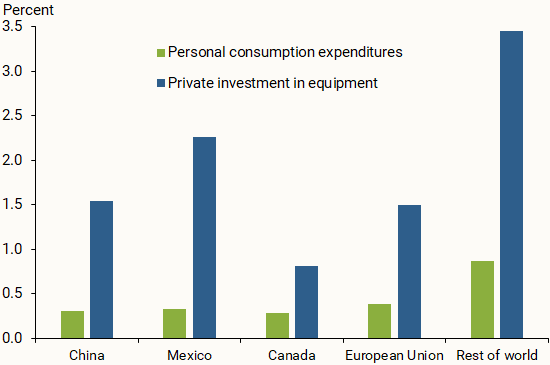

Figure 3 reports near-term estimates for the impact on PCE and PEQ prices from the tariff on all goods imports from China, Mexico, Canada, the European Union, or the rest of the world. The green bars report the effects on PCE prices while the blue bars report the effects on PEQ prices.

Figure 3

Potential impact from a 25% tariff

Focusing on potential effects on PCE prices first, a 25% tariff on all goods imported from China, for example, puts about a 0.3% upward pressure on PCE prices. This estimate reflects the impact of a 25% tariff on total PCE import share from China, which is reported in the bottom bar of Figure 1. If those tariffs are extended to imports from Mexico, PCE prices face an additional 0.3% upward pressure. If the tariff is applied to goods imports from all U.S. trade partners, the potential near-term impact on consumer prices nears 2.2%, the sum of all green bars in Figure 3.

Similarly, these scenarios would imply a potential 1.6% increase of PEQ prices if the tariff is imposed on all Chinese goods imports. This corresponds to applying a 25% tariff on China’s import share on PEQ, as reported in the bottom bar of Figure 2. If the tariff is extended to all goods and countries, this could increase PEQ prices 9.6%, the sum of the blue bars in Figure 3.

These estimates show that the potential effects of tariffs are much larger for investment prices than for consumer prices, partly because their import content is larger. This finding suggests that the introduction of tariffs can have important implications for U.S. businesses’ investment decisions.

Impact of tariffs can be larger or smaller

Our calculations should be considered illustrative, because they abstract from many factors that help determine the ultimate effect of tariffs on consumer and investment prices.

For example, tariffs could have a smaller effect than our estimates if foreign and domestic businesses decide to absorb some of the related cost increases or if domestic businesses change their suppliers. Moreover, consumers may also choose to change their consumption habits when facing higher prices.

By contrast, tariffs could have a larger effect than our estimates if, for example, domestic producers opt to raise their prices when facing less competition, or if tariffed countries retaliate and a new wave of tariffs are put in place. Moreover, many consumption and investment goods are subject to reexporting and reimporting, which can compound the effects of a tariff, as goods are subject to tariffs each time they cross the U.S. border.

Finally, our calculations abstract from movements in exchange rates and the potential responses of policymakers, which may also affect the overall impact of tariffs. Given these caveats, our results are best interpreted as an estimate of the near-term price effect of tariffs.

Conclusion

Tariffs can have a significant impact on prices of consumer and investment goods. Our estimates in this Letter suggest that their impact on equipment prices is likely to be much larger than their impact on consumer prices. Estimates imply that, if completely passed through to finished goods, an across-the-board 25% tariff raises investment prices 9.5%, compared with 2.2% for consumer prices. The former can have important implications for businesses’ investment decisions through an increased cost of capital expenditure.

References

Barbiero, Omar, and Hillary Stein. 2025. “The Impact of Tariffs on Inflation.” FRB Boston, Current Policy Perspectives 25-2, February 6.

Hale, Galina, and Bart Hobijn. 2011. “The U.S. Content of ‘Made in China.’” FRBSF Economic Letter 2011-25 (August 8).

Hale, Galina, Bart Hobijn, Fernanda Nechio, and Doris Wilson. 2019a. “How Much Do We Spend on Imports?” FRBSF Economic Letter 2019-01 (January 7).

Hale, Galina, Bart Hobijn, Fernanda Nechio, and Doris Wilson. 2019b. “Inflationary Effects of Trade Disputes with China.” FRBSF Economic Letter 2019-07 (February 25).

Yale Budget Lab. 2025. “State of U.S. Tariffs: April 15, 2025.”

Opinions expressed in FRBSF Economic Letter do not necessarily reflect the views of the management of the Federal Reserve Bank of San Francisco or of the Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System. This publication is edited by Anita Todd and Karen Barnes. Permission to reprint portions of articles or whole articles must be obtained in writing. Please send editorial comments and requests for reprint permission to research.library@sf.frb.org