John Fernald, senior research advisor at the Federal Reserve Bank of San Francisco, stated his views on the current economy and the outlook as of March 5, 2020.

- Until recently, the COVID-19 outbreak in China appeared to be a modest background headwind for the U.S. economy. In late February, however, the growing spread of the virus to regions outside China—including the United States—became a prominent concern for U.S. financial markets, households, and economy.

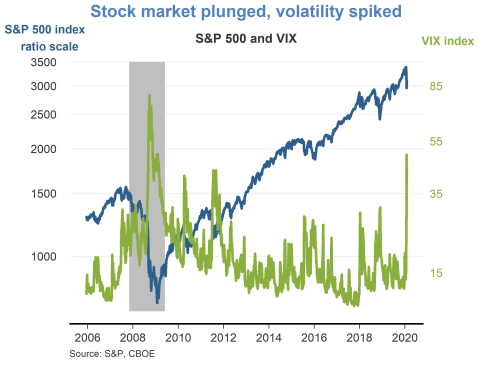

- The Standard & Poor’s 500 index reached an all-time high on February 19 but subsequently plunged as the number of new cases and victims of the disease grew. Stock market volatility, as measured by the VIX index, spiked upwards, reaching its highest levels since the Great Recession.

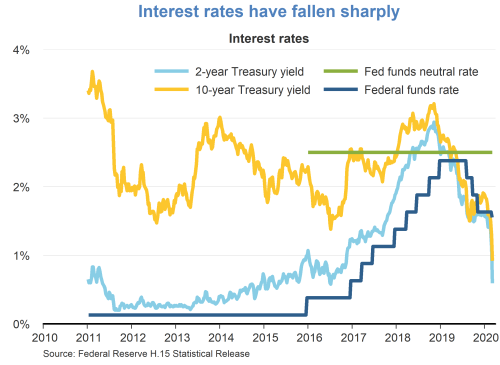

- In recent weeks, interest rates have fallen sharply as investors have sought the safety of government bonds. In early March, the Federal Open Market Committee reduced its target for the federal funds rate by 50 basis points, to a range of 1 to 1¼%. Chair Jerome Powell stated that the purpose of the rate cut was to avoid a tightening of financial conditions that might weigh on economic activity as well as to support household and business confidence.

- It’s far too early to have hard data available to assess how consumer spending—which has been supporting U.S. economic growth—will be affected by COVID-19. One daily measure of consumer confidence shows that, although sentiment held up well through most of February, it started slipping in the last week of the month.

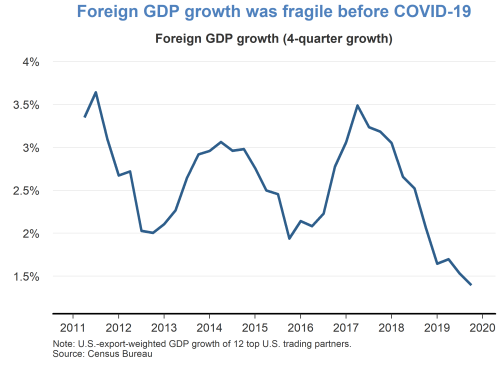

- Slowing foreign growth has posed a headwind to the U.S. outlook for several years for a variety of reasons, including weak domestic demand, trade tensions, and social unrest in some countries. At the end of 2019, foreign GDP (weighted by U.S. export shares) grew at its slowest pace in a decade. The effects of the spread of the coronavirus looks likely to worsen the global situation, at least in the near term.

- Manufacturing surveys in China fell off a cliff in February, as the coronavirus lockdown and factory closings led Chinese production and new orders to plunge.

- Outside China, the manufacturing situation has yet to fully reflect the coronavirus effect. The U.S. manufacturing survey remained expansionary with an index value of above 50. The euro-area survey was better than it has been in the past year although it was still modestly contractionary. One leading indicator of the COVID-19 effect is a rise in supplier delivery lags, consistent with the disruption of supply chains.

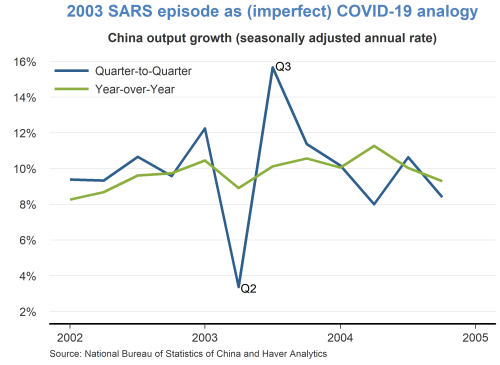

- The 2003 SARS episode provides a comparison for projecting the possible economic effects of COVID-19. In the second quarter of 2003, when China established measures to halt SARS, its annualized quarter-to-quarter growth slowed from 12% to 3% but rebounded in the third quarter to nearly 16% after the virus waned. Thus the downturn was sharp but temporary. Growth then stabilized at around 10%. However, this comparison with COVID-19 is imperfect as SARS was less contagious, though more deadly, and was largely contained to China, Hong Kong, and Taiwan.

- In the present COVID-19 case, China’s measures to contain the outbreak have substantially disrupted its economy as closed factories directly reduce production, households pull back on spending, and financial stress increases because firms, particularly small- and medium-sized enterprises, face severe cash flow challenges.

- As a result of these effects, China’s quarter-to-quarter GDP growth rate in the first quarter of this year is likely to be substantially negative. But, given the sharp declines in the number of measured new virus cases in China, there is likely to be a substantial second-quarter rebound in growth.

- The disruptions in China are spilling over to the rest of the world through supply-chain disruptions as well as reduced demand for foreign exports—and reduced travel and tourism spending abroad.

- In addition, as the virus expands globally, it will weigh directly on foreign economies, including the United States, through the same kinds of supply, demand, and financial stress channels affecting China. How large these effects are outside China will depend on how well the virus is contained through monitoring and quarantines. But the economic effects elsewhere are likely to be less severe than in China.

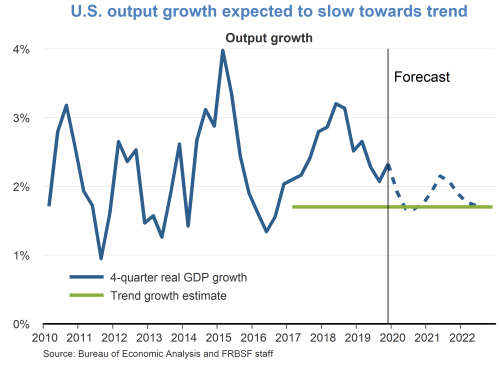

- In the near term, we expect the COVID-19 virus to slow U.S. growth in the first half of 2020 without derailing the medium- and longer-run forecast. U.S. GDP has been growing modestly above trend in recent years. For all of 2020, the COVID-19 virus is expected to slow growth to roughly its longer-run trend. U.S. GDP growth is then expected to rebound modestly above trend, before gradually returning to trend over the next couple of years. This forecast includes the stimulative effect of the additional monetary accommodation put in place this week.

- Our baseline assumption underlying this forecast is that the coronavirus and its economic effects will be largely contained in the first half of the year. Of course, at this time there is no way to know how widespread or disruptive the disease will ultimately turn out to be. So the risks to the forecast appear skewed to the downside.

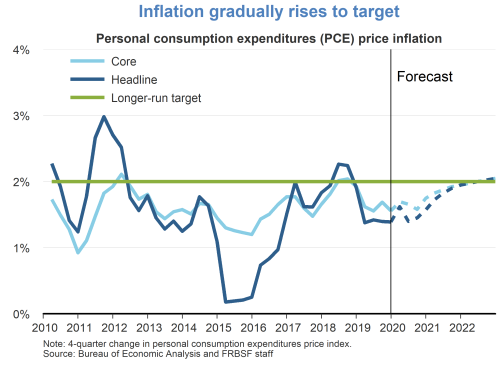

- Inflation has been systematically running below the Federal Reserve’s 2% objective in recent years. We expect inflation to gradually rise to 2%. The recovery in inflation comes especially from the strong labor market, which will continue to put upward pressure on labor costs. The continued labor market strength is consistent with GDP growth that is at or above trend, reflecting accommodative monetary policy and fiscal tailwinds.

TopicsInflation

The views expressed are those of the author, with input from the forecasting staff of the Federal Reserve Bank of San Francisco. They are not intended to represent the views of others within the Bank or within the Federal Reserve System. FedViews appears eight times a year, generally around the middle of the month. Please send editorial comments to Research Library.