Recent research suggests that sustained accommodative monetary policy has the potential to increase financial instability. However, under some circumstances tighter monetary policy may increase financial fragility through two channels. First, a surprise tightening tends to reduce the market value of banks’ equity and raise their market leverage, exacerbating balance sheet fragility in the short run. Second, increases in the federal funds rate have historically been followed by an expansion of assets held by money market funds, which proved to be a source of instability in the 2007-09 financial crisis.

The Great Recession reignited the debate about what causes financial instability, particularly the effects of monetary policy on the financial system. For example, Taylor (2007) argued that the Federal Reserve contributed to the buildup of instability that led to the 2007-09 financial crisis by keeping the federal funds rate too low for too long between 2001 and 2004. Since the crisis, central banks around the world have held their policy target rates close to zero for several years, raising concerns that rising asset prices could quickly reverse and spill over into the real economy. More broadly, there seems to be general agreement that sustained accommodative monetary policy may foster financial vulnerabilities by leading to excess credit for households and businesses, high leverage at financial institutions, and increased risk-taking among investors. For that reason, there were some sighs of relief at the prospect that current monetary policy tightening through raising interest rates would reduce financial instability. By contrast, in this Economic Letter, I introduce two channels through which monetary policy tightening could in fact increase financial instability, and I assess the relative importance of these two channels in the current environment.

Higher interest rates can raise market leverage for banks

Leverage, defined as the ratio of assets to equity, is a standard indicator of risk. It is often measured using book values based on a firm’s balance sheet. The conventional view is that, following an increase in interest rates, banks decrease their leverage. They do this by reducing their debt, that is, their borrowing from depositors and other financial institutions, and reducing their assets, mostly loans and security holdings, relative to their equity. However, this view ignores the short-run reductions in asset and equity valuations that usually follow interest rate increases. Instead, a measure of leverage based on current market prices—given by the ratio of the market value of assets to the market value of equity—captures such reevaluation effects. Measuring leverage using market prices is also particularly important for banks because they face funding constraints that depend on how their assets and equity are valued in the market, as explained in Paul (2017a).

To understand the mechanism using market leverage, consider an example. Assume that a bank owns assets worth $100 billion and has $80 billion in outstanding debt. Hence, its market equity is $20 billion—the difference between assets and debt. The bank’s market leverage is equal to 5—the market value of assets of $100 billion divided by the market value of equity of $20 billion. Next, assume that the central bank raises interest rates, which immediately decreases the value of the bank’s assets to $90 billion and its equity to $10 billion. Given the $80 million of outstanding debt, its market leverage rises to 9—$90 billion divided by $10 billion. Hence, in this example, market leverage increases after a monetary tightening.

Whether or not the reduction in the value of a bank’s equity is sufficient to raise its market leverage before banks adjust their debt is an empirical matter. This requires identifying changes in monetary policy that come as surprises to the market. To this end, I build on the approach developed in Paul (2017b) that uses federal funds futures contracts to isolate monetary policy surprises and integrates those into an empirical model that captures dynamic interdependencies between multiple variables. Among those variables is a proxy for the market leverage of U.S. commercial and investment banks, taken from the data collected by Paul (2017a).

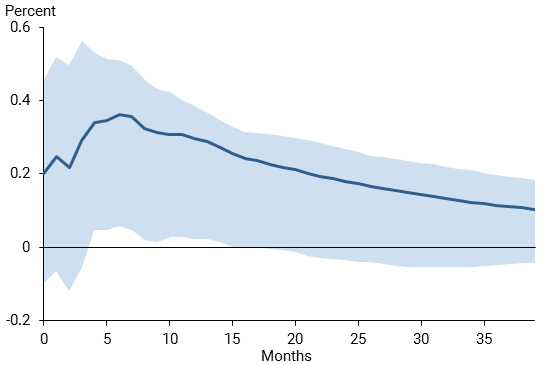

Using this estimated model, I find that an increase in the federal funds rate leads to a decline in industrial production and a fall in banks’ market equity. Importantly, as illustrated in Figure 1, market leverage increases in the short run. Following a rise in the federal funds rate of 0.1 percentage point, market leverage initially increases by about 0.2 percentage point, and this effect takes more than three years to entirely dissipate.

Figure 1

Market leverage response after surprise policy tightening

Note: Estimation sample is from November 1988 through December 2007, with 95% confidence bands.

Hence, banks are subject to short-term interest rate risk, and a monetary policy tightening puts pressure on their balance sheets. This result therefore provides a rationale for avoiding bunched and large unexpected increases in the policy target rate. Instead, the use of forward guidance through communications to steer expectations and gradual increases in interest rates gives banks time to adjust their balance sheets.

There are reasons why the effect documented above might be somewhat weaker or stronger in the current environment. On the one hand, U.S. banks have accumulated a large amount of excess reserves over the past few years—credit balances in accounts at the Federal Reserve in excess of the amounts they are required to hold. The interest on these reserves will rise as the federal funds rate increases. If the average funding costs do not increase one-for-one, then future net cash flows will rise, partly reducing the effects of a surprise tightening.

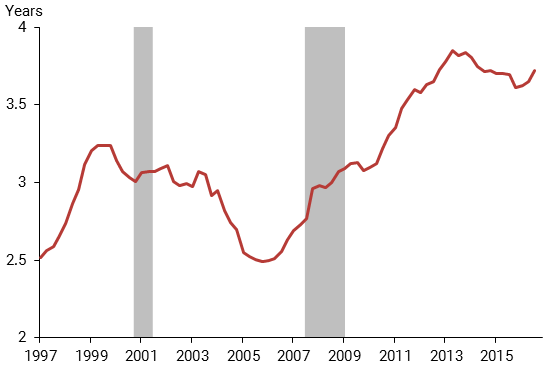

On the other hand, there are some current factors that might amplify the effect. For example, the maturity or repricing gap of U.S. commercial banks—that is, the difference between the maturity of assets and liabilities—has increased since the end of the recession, as shown in Figure 2. The larger the maturity gap, the more exposed banks could be to interest rate risk. This is because banks loan out money at long-term interest rates and finance those loans with short-term borrowing. The cost on this borrowing may fluctuate unexpectedly when central banks change interest rates. Hence, U.S. commercial banks might be somewhat more exposed to interest rate risk at the moment.

Figure 2

Maturity gap between bank assets and liabilities

Sources: Maturity gap is based on data from bank Call Reports; see Paul

(2017a) for details. Gray bars denote NBER recession dates.

Thus, while it is difficult to gauge the exact strength of the market-leverage channel in the current environment, it seems likely that further surprise increases to the federal funds rate target would increase the market leverage of banks. This in turn could weaken the stability of the financial system somewhat, particularly if those surprises were large.

Higher interest rates affect money market funding flows

A key provider of funding for banks and other financial institutions are money market funds (MMFs). MMFs issue shares to investors and invest in quality short-term assets, such as secured and unsecured short-term debt issued by financial firms. In June 2012, these funds financed around 40% of U.S. nonfinancial, financial, and asset-backed commercial paper (a short-term debt instrument) and around a third of certificates of deposit and repurchase agreements (Cipriani, Martin, and Parigi 2013).

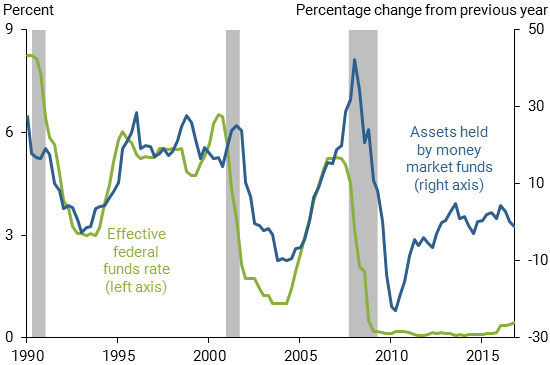

Figure 3 shows that asset holdings of MMFs tend to rise and fall with changes in the federal funds rate. That is because yields on MMF shares move closely with and in the same direction as the federal funds rate. After a monetary policy tightening, MMFs are able to attract investors, and financial firms are encouraged to create debt instruments in which MMFs can invest. These movements are substantial. For example, from 2004:Q1 to 2008:Q4, MMF assets grew from around $2 trillion to $3.8 trillion.

Figure 3

Money market fund asset changes and the federal funds rate

Source: Federal Reserve Board of Governors. Gray bars denote NBER recession

dates.

However, MMFs could also be a source of financial instability. First, studies show that investors who hold shares in MMFs are sensitive to even small yield differences, which can reward MMFs with riskier portfolios that offer higher yields (Hanson et al. 2015). Second, shares of MMFs can be redeemed on demand, which makes them vulnerable to runs and withdrawals if investors perceive that the assets have become less safe. Funding problems for MMFs can spread across the financial system and ultimately affect the real economy, which happened during the financial crisis of 2007-09. These potential risks to financial stability and the close relation between MMF asset holdings and the federal funds rate demonstrate how increases in the federal funds rate could increase financial instability.

To address the financial stability concerns associated with the MMF industry, the Securities and Exchange Commission issued a set of reforms, and a second round of reforms went into full effect in October 2016. These reforms dramatically reshaped the landscape of the MMF industry. Assets held by funds that invest in short-term debt from non-government borrowers, such as financial firms, fell sharply (Chen et al. 2017). MMFs have therefore become a less important source of funding for financial institutions. However, it is unclear whether investors will continue to stay away from such MMFs in the future, even when the federal funds rate increases. Hence, funding flows into MMFs and from MMFs into other institutions should be closely watched over the coming tightening cycle.

Conclusion

This Economic Letter provides evidence of two ways that monetary policy tightening can pose risks to financial stability. First, a surprise monetary tightening can lead to an increase in the market leverage of U.S. banks, pressuring their balance sheets in the short run. And second, increases in the federal funds rate have historically been followed by an expansion of assets held by money market funds, which proved to be a source of considerable instability during the 2007-09 financial crisis.

The first channel provides a rationale for avoiding sudden large and unexpected increases in the policy target rate because such changes can be destabilizing. Regulatory changes in the money market fund industry appear to have weakened the importance of the second channel. Nonetheless, the findings suggest that it would be prudent to pay close attention to funding flows into and out of money market funds in the context of monitoring financial stability.

Pascal Paul is an economist in the Economic Research Department of the Federal Reserve Bank of San Francisco.

References

Chen, Catherine, Marco Cipriani, Gabriele La Spada, Philip Mulder, and Neha Shah. 2017. “Money Market Funds and the New SEC Regulation.” Liberty Street Economics blog, FRB New York.

Cipriani, Marco, Antoine Martin, and Bruno Parigi. 2013. “Money Market Funds Intermediation and Bank Instability.” FRB New York Staff Reports.

Hanson, Samuel G., David Scharfstein, and Adi Sunderam. 2015. “An Evaluation of Money Market Fund Reform Proposals.” IMF Economic Review 63(4), pp. 984–1,023.

Paul, Pascal. 2017a. “A Macroeconomic Model with Occasional Financial Crises.” FRB San Francisco Working Paper 2017-22.

Paul, Pascal. 2017b. “The Time-Varying Effect of Monetary Policy on Asset Prices.” FRB San Francisco Working Paper 2017-09.

Taylor, John. 2007. “Housing and Monetary Policy.” NBER Working Paper w13682 (07-003).

Opinions expressed in FRBSF Economic Letter do not necessarily reflect the views of the management of the Federal Reserve Bank of San Francisco or of the Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System. This publication is edited by Anita Todd and Karen Barnes. Permission to reprint portions of articles or whole articles must be obtained in writing. Please send editorial comments and requests for reprint permission to research.library@sf.frb.org